Collector's Corner

JAPONISME: The Influence of All Things Japanese on Rick Bartow’s Art

Ukiyo-e, a genre of woodblock printmaking that was particularly popular in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868), was an important influence on Rick Bartow’s art. Ukiyo-e illustrated scenes from the “floating world.” Uki translates as floating, yo as world, and e as picture. Originally a Buddhist term meant to convey the concept that earthly life is ephemeral, ukiyo-e became associated with the fleeting diversions of Edo’s licensed pleasure districts and the theater. During this time, the wealthy merchant class was able to indulge in pastimes that their new-found wealth afforded them – the kabuki theater, courtesans, and geishas. Ukiyo-e artists rarely created their own woodblocks. Instead, they worked closely with a carver, who cut the images into wood; a printer, who inked and pressed the woodblocks onto paper; and a publisher, who distributed and promoted the artist’s work. Like his Ukiyo-e counterparts, Rick Bartow worked with Japanese printers and papermakers, as well as gallerists who exhibited and promoted his work: master paper maker Naoaki Sakamoto, master printer and gallery owner Seiichi (Seii) Hiroshima, and gallery owner Toshiaki Yanagisawa. During the course of his artistic career, Rick Bartow created many works that reflected his interest in Japanese art and culture. Among them were preliminary works for posters promoting gallery exhibitions.

Japanese Poster I by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, acrylic on canvas, 24” x 30” (1994). Photo courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Japanese Poster I is a bit of a mystery. According to Dulce Montalvo-Hilts, Assistant Director, Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR, “. . . there are no notes about what the poster was intended for. But what I do know is that this poster was made right after his [Bartow’s] first visit to Japan in 1994.”

The German words der Plakate mean the poster while the term aesthetiche Japanische means Japanese aesthetic. The numbers 22, 11, and 94 indicate November 22, 1994. The Japanese characters are also part of the mystery.

The work is done in a Japanese style with red type on an orange background and features the image of a man with a towel around his neck. Below him is the name Danjūrō VI, which indicates the great kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjūrō VI (1778 – 1799). The name Ichikawa Danjūrō is a name taken on by kabuki actors of the Ichikawa family and is considered the most prestigious of the kabuki stage names. Dulce Montalvo-Hilts also indicated that “At the time, Rick was looking at work by Kunimasa.” Utagawa Kunimasa did a number of portraits of Ichikawa Danjūrō VI and the image that Bartow produced looks very much like them.

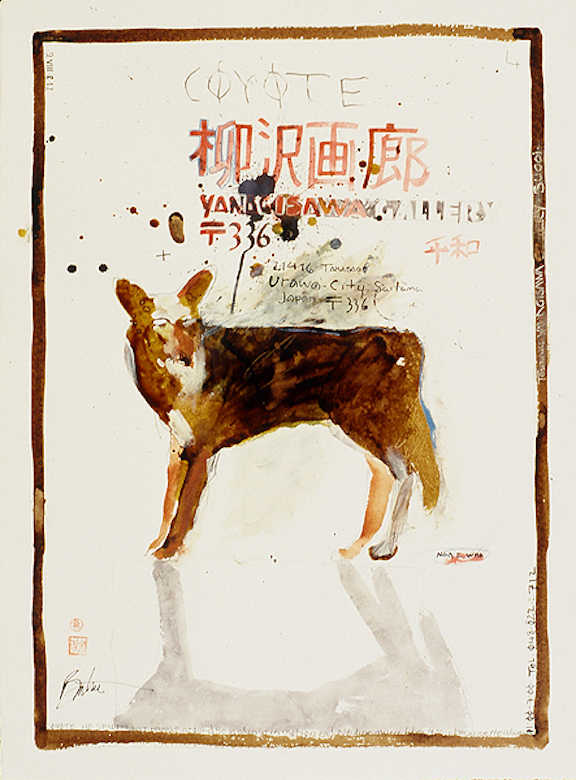

Noon Coyote by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, gouache on paper, 30” x 23” (1995). Photo courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Rick Bartow often used images of animals in his work – Crows, Ravens, Bears, Dogs, Donkeys, and a variety of fish, amphibians, reptiles, and insects. Noon Coyote, which is part of his Japan Sketch Series, features a coyote, one of his favorite creatures. In many Native American stories, Coyote is a trickster who sometimes gets hoisted by his own petard. At the top of the page is the word coyote spelled out in capital letters. Below it are Japanese characters that most probably indicate the Yanagisawa Gallery since the gallery’s name and address are also written below in English.

|

|

|

Japanese chops frequently used by Rick Bartow.

The lower left side of the page includes two of Bartow’s personal red chop stamps, which were made for him by Toshiaki Yanagisawa. The round chop employs a very old Japanese calligraphy format called tensyo to spell Rick’s name and it is an image of a crow, which Bartow considered his guardian spirit. The square chop is a bit of a joke since it reads roughly as “He Works Standing Up.” There are two kanji on this stamp.

Japan Poster I by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, gouache and graphite on paper 26” x 20” (1995). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Japan Poster I is among the many works Rick Bartow created to be the basis for posters. In this case, the German words Plakate aus Japanisch mean Poster (or placard) from the Japanese. The Japanese kanji most likely reads the same. As for the image, one can only make an educated guess. It is known that Bartow definitely had an interest in the work of Utagawa Kunimasa and the figure in Japan Poster I could either be the great kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjūrō VI, or Ichikawa Omezô, another Kabuki actor who was immortalized by Kunimasa.

Sharaku Kibuki /Japan Sketch by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, mixed media on Waterford Paper, 30” x 22.5” (1995). 2016-17 Promised Estate Gift Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Eugene, OR. Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Bartow’s Sharaku Kibuki /Japan Sketch is also mysterious in a number of ways. At this point, the Japanese calligraphy remains untranslated and the work has a number of strange elements. Written up the right side of the work are the words Yanagisawa Gallery and the gallery’s address. Along the left side of the page are the words Jamison Thomas Gallery, followed by the German In jahr final exhibition Juli 6, meaning “year’s final exhibition July 6.” The Jamison/Thomas Gallery started in Portland, Oregon, and later opened a branch in Manhattan. One is left to wonder if two simultaneous exhibits were taking place – one in Tokyo, Japan, and one in the United States. Towards the top of the page is the name Willam Jamison, one of the owners of the Jamison/Thomas Gallery. At the top right of the page, Bartow has written “Japanishe Skizzes für Julie Swan” upside down, which means “Japanese sketches for Julie Swan.” Julie Swan was Rick Bartow’s wife.

The title of the work, Sharaku Kibuki most probably refers to Tōshūsai Sharaku, a ukiyo-e print designer known for his portraits of kabuki actors. The images in Sharaku Kibuki/Japan Sketch may be portraits of one kabuki actor or multiple actors. However, it is difficult to determine exactly who is being portrayed though it might be Ichikawa OEMs

Like many of Bartow’s works on paper, Sharaku Kibuki /Japan Sketch contains splats, splotches, what appear to be paint drippings, and the Roman numerals XV, which is another of the piece’s mysteries.

Azabu Kasumityou (Japan Sketch Series) by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, graphite, ink, gouache, acrylic, mixed media on Japanese papers, 21.5” x 9.5” (1997). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

A collage of previously drawn and painted papers, Azabu Kasumityou presents the viewer with an image of a kabuki actor looking left. It is unclear whether Bartow created a portrait of a particular actor based on prints he had seen or if the face is one created solely from his imagination. In ukiyo-e prints, actor’s names were not given, but fans would have recognized their favorite kabuki stars. However, based on a number of 16th century prints, Ichikawa Danjūrō VI, Ichikawa Ebizō (aka Ichikawa Danjūrō V), and Ichikawa Omezô are contenders for whom Bartow may have portrayed.

On the top of the page are the words Paper Nao. The address of the paper boutique is also given. It is at this establishment that Bartow acquired much of the materials he used in creating his works on paper. To the right of these words are Rick Bartow’s personal stamps. On the lower part of the page, below the image, Bartow wrote “Azabu Kasumityou Gallery,” its address as well as its phone and fax numbers. Under this, he printed his name in large capital letters. To the left of his name are the numbers 4, 10, 97 indicating the date of October 4, 1997.

In an email Charles Froelick, owner of the Froelick Gallery, explained that Bartow made this piece to celebrate that he was working with Seiichi Hiroshima’s gallery – Azabu Kasumityou. However, he doesn’t think that the piece was brought to Japan to be exhibited at Seiichi’s gallery. He also explained that, “The letters ‘CHIE’ in the lower right are from a former work Rick had made with ‘CHIEF’ written on it, he tore it up and added that to make this larger sheet. None of the collage elements were commercially printed . . . all hand-lettered, hand-painted by Rick. Rick made these for various galleries or events over the decades.”

Azabu Amaryllis (Poster) by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, mixed media on handmade nao paper, 23” x 17” (1997). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Clearly, a work that became a poster for Bartow exhibitions, Azabu Amaryllis contains a great deal of visual information beyond that of three wilting amaryllis in a narrow glass bottle on a brown background. Below this central image, Bartow wrote, “Gallerie Azabu Kasumityou” in large letters. Under this, he added, “Bartow Exhibition of Drawings.” He also hand-printed information around three sides of the page.

Along the right side, Bartow wrote what is clearly “Froelick Adelhan, or Adelhant Gallery, Portland, Oregon 97208.” The actual name of the gallery was Froelick Adelhart.). He also wrote the gallery’s phone and fax numbers.

On the right side of the page, Bartow wrote, “In Japan 1997 Yanagasawa Gallerie – Onawa City – Oguni Town IT’NL Exhibition Hall.”

On the top of the page, “Oshiaki Yanigisawa 0488222712 Azabu Kasumityou” is written upside down,

According to Charles Froelick, Rick had three exhibits in Japan in the Autumn of 1997, two of which were gallery shows. One was Rick Bartow Drawings: Flowers and Animals at the Yanagisawa Gallery, Saitama City; another was Portraits at the Azabu Kasumicho Gallery (also written as Azabu Kasumisou and Azabu Kasumityou), in Tokyo, and Drawings at Oguni-Geijutsumura-Kaikan, an exhibition hall.

Jennifer by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, graphite, gouache, mixed media on paper, 13” x 17” (1997). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Just who was Jennifer and why did Rick Bartow choose to immortalize her? It is an obvious question anyone may have when looking at Jennifer, a work on paper that is part of the artist’s Japan Sketch Series. However, her identity is one of the many mysteries encountered in Rick Bartow’s art.

Sideways, on the right side of the page Bartow wrote “Toshiaki Yanagisawa,” plus the gallery’s address, and nearby on the lower part of the page he put his kanji stamps though this time the square one is placed above the circular one, which is unusual.

On the left side of the page, Bartow drew the image of a beautiful woman with an enigmatic smile who is wearing a kimono of black, lavender, turquoise, tan, and muted yellow. Her image is on a background of brown, red, and tan. To the left of the woman Bartow wrote his name in capital letters and below it are Japanese characters, which may also represent his name.

Bartow also wrote around the page. Along the right side of the page, Bartow hand-printed the words “Gallery of Tribal Arts Vancouver BC,” plus the gallery’s phone number. He used no punctuation.

Across the bottom of the page, Bartow wrote, “Froelick Adelhart Gallery,” plus the gallery’s address and phone and fax numbers. Just above this is what appears to be a dedication in German, but it is not possible to decipher.

In the upper lefthand corner of the page, apparently in German, is, perhaps, another dedication, or reference to people the artist knew, but the words are not clear.

Bartow also did a number of studies for posters done in the style of Hakuin Ekaku, usually referred to simply as Hakuin, which is his surname. Hakuin became a Buddhist monk at the age of fifteen and at thirty-one was already a head priest of a temple. He was noted for his compassion and desire to help all living beings. Although he is well known for his painting, Hakuin did not take up the art form until he was almost sixty. He died at eighty-three in Hara, the same village in which he was born. Two of Bartow’s loveliest works in this vein are Shoki the Demon Queller and English Daruma.

Shoki the Demon Queller by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, ink, graphite on handmade paper, 72” x 26” (1998). 2016 Charitable Gift: Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Eugene, OR. Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Shōki was a physician during China’s Tang era (500 – 600 B.C.). Unfortunately, he was considered to be very ugly. In order to advance his career so that he could enter imperial service, he took the national examination for these positions and scored first place among all candidates. However, when Shōki was presented to the emperor he was rejected because he was so homely. In utter shame, Shōki committed suicide. Learning of this, the emperor was filled with remorse and ordered that Shōki was to be buried in the green robe of the imperial clan. As a sign of his gratitude, Shōki’s spirit pledged to protect the ruler and all male heirs from demons, plagues, and evil. Shōki’s popularity was at its highest during the Edo period (1615-1868) in Japan. Today, Shōki is mostly forgotten and neglected by most of Japan, except perhaps in Kyoto where he is still regarded as the guardian against evil spirits, plagues, and protector of homes, especially those with male children.

In Rick Bartow’s Shōki the Demon Queller, his Hakuin-style study for a poster, he captures the figure’s ugliness and intensity. The figure’s eyes are wide and looking to the right. Rather than using bold colors the artist has employed muted tones of tan, brown, and black on an off-white background.

English Daruma by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, ink, graphite on handmade paper, 72” x 26” (1998). 2016 Charitable Gift: Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Eugene, OR. Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Draruma are dolls that are popular with the Japanese as well as with tourists. They are modeled after the Buddhist monk Bodhidharma. Daruma is the Japanese name for Bodhidharma. Biographically, little is known about him and most of what has come down through history is legend, which claims that he sat facing a wall in meditation for nine years without moving. This caused his legs and arms to fall off. According to another tale, Bodhidharma fell asleep during his nine-year meditation and when he awoke he was so displeased with this failure that he cut off his eyelids to avoid this ever happening again. Bodhidharma was usually depicted as bad-tempered, heavily bearded, wide-eyed, and looking decidedly non-Chinese. This may be because, according to lore, he came to China, mostly likely from India, to preach Buddhism. Today, Japanese daruma dolls are modeled after Bodhidharma: They are usually round and have no arms, legs, or eyes. Daruma comes in a wide variety of colors, depending on the type of wish the buyer wants to come true.

Bartow based his poster study English Daruma on depictions of Bodhidharma. Why he titled this work English Daruma is yet another “Bartow mystery.” Nonetheless, it is a strong piece. The large head, wide, staring eyes, and heavy beard create an intense figure. Above it, bold red letters proclaim, “Bartow in Japan – 3 Yamanota-Tokyo Urawa.”

Pucker Poster by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, mixed media on paper 30” x 22” (1999). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

The first thing the viewer notices about Rick Bartow’s Pucker Poster is a head with wild hair, bulging eyes, protruding red lips, and copious neck folds. Although mostly devoid of color, there are splashes of yellow and red as well as brown for the figure’s hair. Nonetheless, the image is arresting. The contents of the page are framed by a brown border, which contains not only the strange-looking man, but a great deal of written content – much of which is legible while some of it is not. Towering over it all is the name Bartow written in capital letters.

Along the right side of the page, Bartow wrote, “Dibutto Accurela Exhibicion” (Accurate Drawing Exhibition), followed by “Gallarie Peiper Riegraf” and its address in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. To the left of these words are Japanese characters written sideways.

In the upper lefthand corner and descending downward, Bartow wrote, “Toshiaki Yanakisawa Gallery,” plus its contact information; “Asabu Kasumicho Gallerie,” and its information; and “Paper Nao,” with its address. Below this, the artist wrote “KORIE.” However, whether this is a person’s name or a word in a foreign language is unknown. It is yet another mystery.

Below the figure’s ear, over a yellow patch, Bartow wrote “Nach Shohaku,” meaning after Shohaku. This is a reference to Soga Shōhaku (1730 – 1781), a painter during Japan’s Edo period. Shōhaku’s work was different from that of his contemporaries, not only because of his no longer fashionable brush style but because he created grotesque representations of important people.

Below this reference, written in German, Bartow has written what appears to be “Nach Spag,” which means after spaghetti. If this is the case, this may be the artist’s humorous allusion to the figure’s hair.

Under this Bartow wrote “Froelick Adelhart Gallarie”, which represented him as well as the gallery’s address.

To the right of the figure, Bartow signed his name followed by two nines, written one above the other, signifying the date of the exhibition for which the poster was created. Below this, Bartow wrote a message. Unfortunately, only the beginning of it can be read: “I always think of them when . . . .”

The title of this work may be a reference on two levels. It may, of course, simply indicate the figure’s puckered lips. It may also be a sly reference to Puck, a character in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream who is responsible for the mischief that occurs throughout the play.

Otsu-e (detail) by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, ed. 18/20, 4” x 4” (1999). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Curiously, Pucker Poster bears a striking resemblance to Otsu-e, one of Rick Bartow’s drypoint etchings, which was also created in 1999. Otsu-e, meaning pictures from the town of Otsu, became a sort of cottage industry in 17th-century Japan. Local people developed a type of folk art similar to ukiyo-e, but less artistic. The features of many of the characters portrayed were frequently exaggerated. In both Pucker Poster and Otsu-e Rick Bartow created characters with wild hair, bulging eyes, an outsized nose, and a heavily wrinkled neck. Could these two figures be one and the same person? We may never know. Part of the enjoyment of Bartow’s art are the many mysteries contained in it.

Throughout his artistic career, Rick Bartow often took inspiration from Japanese pen and ink drawings, ukiyo-e, utsu-e, and erotic shunga prints, as well as scroll paintings. Bartow spent time in Japan working with printers and papermakers, as well as gallerists who exhibited and promoted his work such as master paper maker Naoaki Sakamoto, master printer and gallery owner Seiichi (Seii) Hiroshima, and gallery owner Toshiaki Yanagisawa. These collaborations yielded spectacular results such as prints and the works on paper the artist created for numerous posters.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Charles Froelick, owner of the Froelick Gallery, and Dulce Montalvo-Hilts, Assistant Director of the Froelick Gallery, for their invaluable assistance with this article.