Collector's Corner

AIRING DIRTY LINEN IN PUBLIC: Inuit Artists Grapple with a Sensitive Subject

Every family and every culture, for that matter, has its version of “Don’t air your dirty linen in public.” The Inuit are no exception. As with all people, the Inuit want to present their culture in the best possible light and outsiders, for the most part, have been content with benign and often romanticized images of Inuit life as it was once lived on the land and charming depictions of Arctic wildlife. Inuit artists are acutely aware that the art market (consisting mostly of Canadians living outside of the Arctic, Americans and Europeans) prefers colorfully appealing works and, to a large degree, that’s exactly what was produced. However, over the last thirty years this has changed in large degree because of a number of museum exhibits as well as through the efforts of Pat Feheley, owner of Feheley Fine Arts in Toronto, and Robert Kardosh, owner of the Marion Scott Gallery in Vancouver.

When I first began collecting Inuit art I had no idea that works dealing with dark themes even existed. That changed in 1999 when I saw Three Women, Three Generations: Drawings by Pitseolak Ashoona, Napatchie Pootoogook and Shuvinai Ashoona at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. I saw images of suicide, spousal abuse, and the exploitation of women that had been produced by Inuit artists, something I had never before seen. Inuit artists are extremely cognizant of the fact that their work must appeal to collectors, many of whom are often notoriously conservative in their tastes. The Annual Cape Dorset Print Collection, for example, rarely contains any images that in any way could be considered controversial. Nonetheless, over the years a number of artists did create highly personal drawings. Unlike prints, drawings are not bound by the market-oriented printmaking system and in this medium artists could deal with sensitive or controversial themes. For many years, much of this work was never seen by the public, but a number of astute collectors did buy such drawings when they were offered. As collectors expressed a desire to acquire works that dealt with the more difficult aspects of Inuit life, galleries have been more willing to offer them for sale

Kananginak Pootoogook and his niece Napachie Pootoogook were the first Inuit artists to create highly personal drawings on controversial subjects. While Kananginak had a gentle touch, even with problematic content, his niece Napachie took a more hard-edged approach. For many Indigenous people, alcoholism is a sensitive topic since, more often than not, they have been stereotyped as drunks. It is understandable that many Inuit feared that revealing this problem to the world at large through art would simply reinforce the stereotype. Artists, such as Kananginak, Napachie, and those who followed them, faced criticism from members of their community and possible rejection from collectors whenever they veered from what was expected. “It just isn’t done!” seemed to be the prevailing sentiment. In spite of this attitude, however, it was done.

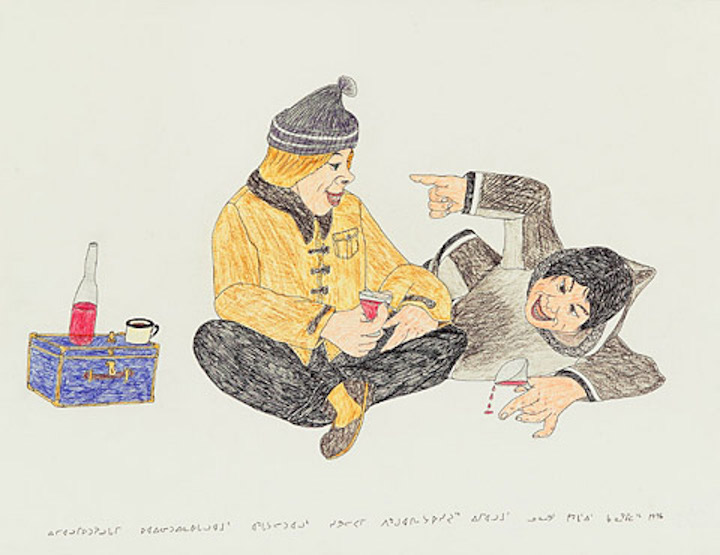

Untitled (White Man and Inuk Drinking) by Kananginak Pootoogook, pencil crayon and

ink, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 20”h x 26”w (1996). Translation of the Inuktitut script: “This is the Ink man’s first drink ever. Even though it’s only wine he is very intoxicated. This is the beginning of alcoholism.” Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of the Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

At this point in time, Kananginak Pootoogook is primarily known for his realistic images of Arctic wildlife. However, there are those who feel that, ultimately, Kananginak will be remembered for chronicling the effects outsiders-whalers, traders, missionaries, and policemen-had on Inuit culture. Untitled (White Man and Inuk Drinking) is one such work. This drawing deals with the problems created by the introduction of alcohol. Kananginak often uses gesture or body position to signify meaning. In some ways, his drawings dealing with humans are like silent movies – certain conventions must be understood in order to interpret the artist’s intention. In Untitled (White Man and Inuk Drinking) both men are inebriated, but the Inuk is seemingly more so. The White man sits upright, holding his drink and smiling while his drinking companion is sprawled on the ground gesturing, spilling his drink, and wearing a foolish expression. For centuries, wine has been a part of European culture, and, over time, White people developed a certain amount of tolerance to alcohol. This is not the case with the Inuit and the introduction of alcohol had tragic results that continue to this day. To emphasize this, Kananginak employs the color red to draw the viewer’s eye to the bottle of wine and the glass held by each man, suggesting the devastating role alcohol has played in modern Inuit culture.

Untitled (Alcohol) by Napachie Pootoogook, pencil crayon and ink, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 20”h x 26”w (1993/94). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Gallery Phillip, Toronto and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Late in her career Napachie Pootoogook created a body of work realistically depicting Inuit life, including vices introduced by outsiders, but from a woman’s perspective. In an email at the time I acquired Untitled (Alcohol), Phillip Gevik, Director of Gallery Phillip in Toronto stated, “. . . Napachie is known for depicting the realities . . . of Inuit life. This scene is intended as social commentary – once Aboriginals began re-locating to communities, they began to partake in activities introduced to them by white men. One of these was, of course, the consumption of alcohol.” Gevik further explained that Napachie said she used alcohol because she believed that is what she was supposed to do, before realizing its effects. Untitled (Alcohol) illustrates the impact drinking has on an entire family, not just one person. A mother, child in arm, struggles with a man (presumably her husband) who is holding a bottle in one hand and a stick in the other while nearby another man lies unconscious. The dysfunction and violence created by alcoholism are clearly evident in the drawing.

Composition (Smirnoff Vodka) by Shuvinai Ashoona, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), colored pencil & ink, 11” x 8 3/8” (2021). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Art, Toronto and Dorset Fine Art, Toronto.

Composition (Smirnoff Vodka) by Shuvinai Ashoona is a more recent take on the problem of alcohol consumption among the Inuit. At the time I acquired this drawing in the spring of 2022, I already had five drawings and fourteen prints by the artist in my collection. However, this particular work struck me as something else again. Much of Shuvinai’s work is fantastical and often contains elements of the surreal and whimsical. At times, she seems downright obsessive about even the smallest details in her work. Composition (Smirnoff Vodka) makes the viewer aware of the ills of alcohol consumption with regard to the Inuit, but it does so subtly. Shuvinai indicates what the two figures in the drawing are celebrating by the red paper the person on the left is holding, which reads “Happy New Year.” Behind this person is a sign stating “Grill’s & Bar’s And Beer.” (The apostrophe used in the words Grill’s and Bar’s is grammatically incorrect, for plural words in English, but it doesn’t really matter. English is not Shuvinai’s first language and such errors simply add to the charm of her work. In addition, with the word Grill’s Shuvinai may actually have meant Girls.) The Inuk on the right side of the drawing is holding a bottle with the words Smirnoff Vodka, and behind him on a building is the word Bar. The two figures hang on one another, clearly drunk, but what makes this work strangely compelling is the look on each face, which gives this work an expressionistic quality. Shuvinai, being the artist she is, packs a great deal into her art. Hovering above the scene are four spheres that resemble Earth. These enigmatic planets make an appearance in a number of Shuvinai’s works. What they represent is anybody’s guess and their meaning may change depending on the print or drawing in which they appear.

Alcohol abuse has affected cultures and families across the globe. It is not a problem indicative of one group of people alone. Although Indigenous peoples were introduced to alcohol by Europeans and those of European background, unlike them, they did not have a tolerance to it built up over generations and were more susceptible to its effects. Nonetheless, despite the fact that alcoholism is a cross-cultural issue that is not confined to one race, nationality, or religion, the Indigenous people of the Americas have often been unfairly stereotyped as drunkards. It is no wonder, then, that among the Inuit, as with other Native groups, exposing this delicate and painful issue to the outside world is problematic. Despite facing condemnation from their own community and the possibility of reinforcing a negative stereotype in the world beyond the Arctic, a number of Inuit artists have chosen to address the topic of alcoholism in their art. Having done so is nothing less than courageous.