King Galleries Blog

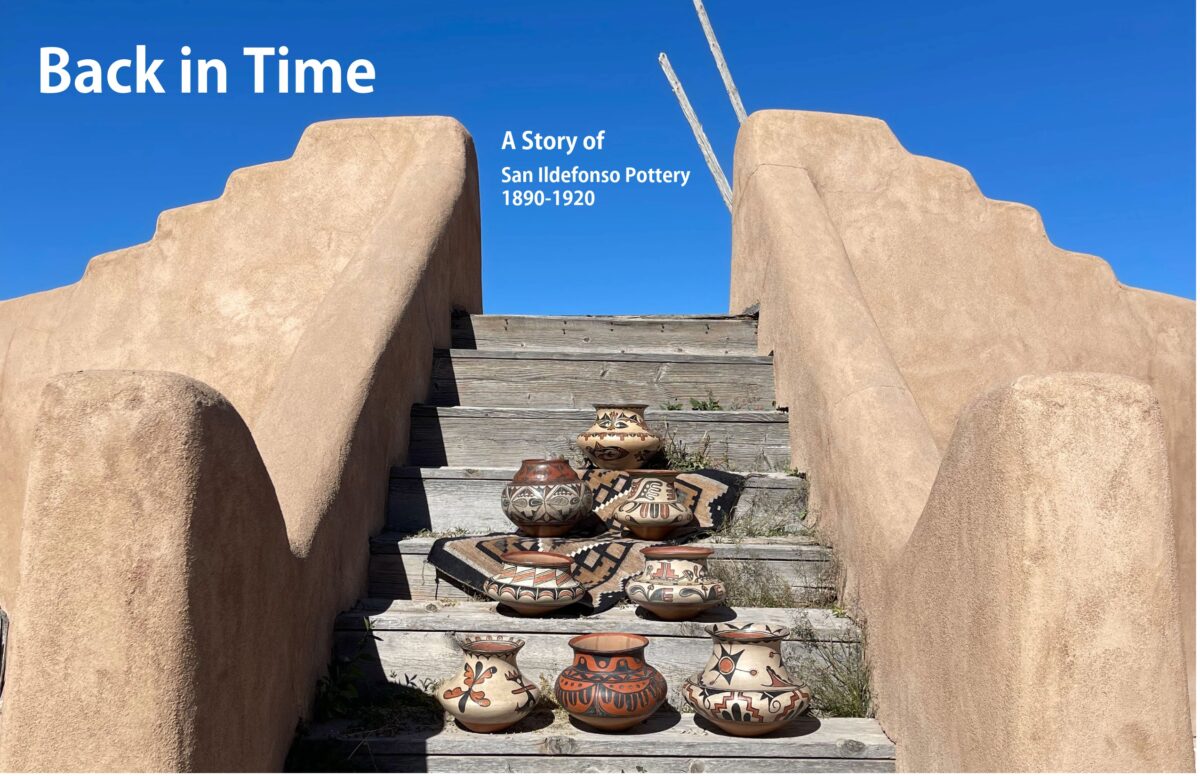

“Back in Time: San Ildefonso Pueblo Pottery 1890-1920”

by Charles S. King

Black, white, red, and brown clays, when combined and layered, are the foundation of polychrome pottery at San Ildefonso Pueblo (Powohgeh Owingeh) in New Mexico. The early styles of this pottery, called Ogapoge Polychrome, were made from around 1760 until the early 1880s. They consisted of black and red designs on a white clay background. The pottery was made for trade or for utilitarian uses by the residents of the Pueblo. The arrival of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway in 1880 changed the economic landscape of the Southwest. Potters from the Pueblos, including San Ildefonso, began to make vessels to sell to the passing visitors and the growing regional population.

|  |  |

| San Ildefonso Polychrome, pre-1915 | San Ildefonso Polychrome 1915-20 | San Ildefonso Black-on-Red |

By 1900, two distinctive styles of pottery were being made at San Ildefonso: black-on-red and polychrome. The colorations and clays were distinctive to several of the Pueblos in the region, but the shapes, the dynamic creativity of the designs, and the personalities of the potters themselves have made San Ildefonso polychrome wares iconic. The pottery was almost always formed by the women of the Pueblo. Each piece was coil-built from clay that was collected locally. The bottoms of the jars were often indented, so that a piece might be carried on the head in addition to stability when placed on a compacted dirt floor. Water jars, storage jars, and bowls were among the classic shapes made at the Pueblo. Once the vessels were formed, they were ready to be painted with designs.

The surface of the San Ildefonso polychrome pottery had a white clay slip that was applied to the top two-thirds of the vessel. The lower third would remain the natural color of the clay, with a band of red clay as a border between the two colors. After about 1910, there was a change, and the white slip was extended all the way to the base. This created more surface area for designs on the pottery. The white clay area was polished with either a stone or a rag, and then it was painted. The painting was typically done by men, but there were an equal number of women who also painted pottery. It is a testament to the community of the Pueblo that a piece might be painted by a woman’s sister, husband, brother, or even neighbor. Once the designs were finished, the vessels would be traditionally fired outdoors.

Black-on-red vessels, with a polished red surface and black painted designs, were less common. The paucity of colors created a greater reliance on form and design to capture the eye of the viewer. Only the most adept of the San Ildefonso potters made pieces in this style. San Ildefonso pottery made before 1920 was not signed by the potters. This raises the question of how to identify individual potters. Each had distinctive shapes for which they were known, including a unique style of elongated neck, shoulder, polishing (or not) on the inside of the neck, or a specific color on the rim. Equally, designs were a “signature,” with the painter often using specific imagery, such as thin lines or bolder strokes, or distinctive spacing of designs on the vessel.

Luckily, many pieces collected directly from the San Ildefonso potters between 1880 and 1920 serve as a “primary source” of material for continued research and identification. When discussing unsigned San Ildefonso pottery from this period, most pieces are associated with the name of the potter, not the painter. Careful research continues to identify the names of both the potter, who made the graceful form, and the painter, who decorated the vessel with a sublime hand.

|  |  |

|

Tona Peña (1847–1905), known as Ba Tse, or Yellow Deer | Marianita Roybal (1843–?) | Ignacia Peña Sánchez (1865–?) |

Among the earliest named potters from San Ildefonso were Tona Peña (1847–1905), who was known as Ba Tse or Yellow Deer in Tewa; Marianita Roybal (1843–?); and Ignacia Peña Sanchez (1865–?). Each was actively making pottery in the late 1890s. Marianita Roybal was famous for her storage jars and may be one of the first Pueblo potters to sign a piece of her work by making her name part of the design. Tona Peña was equally adept at large vessels— both polychrome and black-on-red pottery—and complex designs. Ignacia Sanchez is considered to have been among the first at the Pueblo to create inwardly edged rims to hold her stylized lids. The painting on her pieces is also immediately recognizable for its use of negative space and bold designs that appear more modern than ancient. All of these women were important not only as teachers but also as matriarchs of families of future pottery makers and designers.

Florentino and Martina Montoya

Tona Peña was the mother of Martina Peña (1856–1916), who married Florentino Montoya (1858–1918). Together, Florentino and Martina became among the best-recognized makers of polychrome pottery. Martina’s shapes had an individually artistic form that is easy to recognize. Her pieces with a rounded neck extending up from an indented shoulder, and her wide-shoulder water jars, are among her classics. They were the first to extend the white slip to the base, creating more space for Florentino’s effusive painted designs. In the early 1900s, they moved for a short while to Cochiti Pueblo and introduced the Cochiti white clay to San Ildefonso as a base color for polychrome pottery. Florentino would often intentionally mismatch the colors or designs on his pieces instead of maintaining a consistent repetition of color or imagery on the jar. For example, the leaves of a plant would all be painted black, except for one set, which would be painted black and red. Florentino also looked beyond the designs of San Ildefonso, using imagery from other Pueblos, being especially influenced by the detailed linework of Zuni pottery. Just as Martina’s vessel shapes were unique, Florentino had his own signature designs and a spectacular painting style.

Dolorita Vigil

Florentino and Martina’s niece, Dolorita Vigil (1883–1918), was not a prolific potter but followed in their distinctive style of fully designed pottery. Her career as a dressmaker seems to have influenced her painted designs, which often appear to have the quality of “embroidery” in the placement and flow of designs and the painted inner rims of her vessels.

Dominguita Pino

Dominguita Pino (1860–1948) was already famous by 1900 for her black-on-red pottery. She created a distinctive form with a very wide shoulder and straight neck extending into a sharply turned-out rim. This shape served as a signature of her pottery and one that was adapted with slight variations by her daughter, Tonita Roybal (1892–1945). Dominguita’s designs on the neck differed from the imagery on the shoulder, but all were fluid and complex, creating a complete concept.

Tonita Roybal

Tonita Roybal became as well known as her mother, first for her black-on-red pottery and later for her polychrome vessels. Tonita’s brother, Crescencio Martinez (1879–1918), and her first husband, Alfredo Montoya (1892–1913), were both sought after for their exquisite and creative painting. It may well be that their creativity opened the door for Tonita, as she painted her pieces from the mid-1910s through about 1925, when her second husband, Juan Cruz Roybal, began to paint the exterior of her pottery more consistently.

Maxilliana “Anna” Martinez

Cresencio was married to Maximilliana “Anna” Montoya Martinez (1885–1955), who was also considered among the best painters of designs on pottery. Anna not only painted her own pottery but was noted for painting pottery for Marianita Roybal as well as for her own sister, Maria Martinez.

Nicolasa Montoya

Maria Martinez (1887–1980) often recounted watching her aunt, Nicolasa Peña Montoya (1863–1904), make pottery with her husband, Juan Montoya. It was her aunt who encouraged Maria to begin making pottery. Nicolasa had a short career but was known for her own signature shapes, with narrow bases and low shoulders that extended into long, straight necks. These angular shapes continue to amaze with their balance and the sophistication of their coil-built forms.

|  |

Maria & Julian Martinez

In 1904, when Maria married Julian Martinez (1885–1943), she was already making pottery. Her pieces before this time had been painted by Cresencio Martinez, Alfredo Montoya, Anna Martinez, and other relatives. Once Maria was married, it was Julian who began to paint their polychrome pottery. Julian was quickly recognized for the precision and creativity of his designs.

Julian painted with a worldview, incorporating designs that were often unique and unexpected. The Panama California Exposition, which opened in January 1915, had a pavilion featuring potters from San Ildefonso, including Maria and Julian Martinez, and Tonita and Juan Cruz Roybal. It was around this time that Maria began making some of her first exceptionally large pieces. Their shapes were inspired by the work of earlier San Ildefonso potters but had a new sophistication of form, with rounder shoulders, short necks, or sloping sides. Her pottery became perfect “canvases” for Julian. His designs on the polychrome and black-on-red vessels featured a creative composition that allowed a great deal of open space and utilized different designs on the neck, shoulder, and base. Thin “fine lines,” hachure, and checkerboard patterns contrasted with bolder, painted areas. Traditional San Ildefonso imagery was combined with ancient pottery designs. Much like the San Ildefonso potters of the recent past, Julian created a new visual language on the pottery in concert with Maria’s shapes, reflecting the changing world around them.

The era of polychrome and black-on-red pottery declined after 1922. While the few San Ildefonso potters who were still working knew how to make these styles, they became less popular among the newer collectors and purchasers of Pueblo pottery. Tonita Roybal, Susana Aguilar (a daughter of Marianita Roybal), Ramona Gonzales (a daughter of Ignacia Sanchez), Anna Martinez, Rose Gonzales, and Maria Martinez would still create spectacular polychrome works, with their spouses painting the designs. Polychrome pottery was time-consuming to make and did not sell as well as the new black polished and painted pieces. The arrival of the “black-on-black” pottery outshone the polychrome pottery, as it was a new style for a modern age.

All items in this catalog are attributed when possible, within the bounds of current research. Thanks to my many mentors in the realm of early San Ildefonso pottery over the years, including Robert Nichols, Robert Gallegos, Al Anthony, Dick Howard, Martha Struever, Johnathan Batkin, Russell Sanchez, and others. Thanks as well to the Pueblo of San Ildefonso for allowing us to bring a group of historic pieces back to the Pueblo to be photographed.

Key Takeaways

- San Ildefonso pottery features black, white, red, and brown clays, creating iconic polychrome styles primarily made by women.

- The introduction of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway in 1880 shifted pottery production towards trade for visitors.

- Distinctive styles include black-on-red and polychrome, which evolved from utilitarian to highly artistic forms.

- Key figures in this tradition include notable potters like Tona Peña, Marianita Roybal, and Maria Martinez, who contributed to the legacy of San Ildefonso pottery.

- The popularity of polychrome pottery declined after 1922 as modern styles, like black-on-black pottery, gained favor.