Regina Cata (who was Spanish and married to Eulogio Cata of San Juan Pueblo) was an employee at the San Juan Day School. She encouraged the formation of an art club to make mantas, ceremonial regalia, and household items embroidered by local Pueblo women. The lessons learned in the embroidery of this club would later appear as inspiration in the carved style of pottery in the revival.

In 1930 Regina brought together a group of eight women who began this San Juan pottery revival. Regina Cata, Crucita Cruz, Luteria Atencio, Reycita Trujillo, Tomasita Montoya, Crucita Talachy (Atencio), Gregorita Cruz and Crucita Trujillo. Most likely they had seen the success of the pottery revival at San Ildefonso and Santa Clara Pueblos in the 1920’s. Their initial idea was to revive a pre-Spanish style of pottery. They took trips to Poge (the Ohkay Owingeh ancestral village) and also to the Museum of New Mexico, in order to find inspiration.

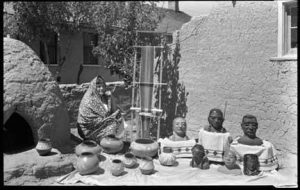

While she helped to begin the 1930’s pottery revival, she is better known for her cloth dolls than her pottery. In 1936 she began to work alone on her dolls and clay busts. From 1940-60, her dolls could be found in a variety of museum exhibitions. She had an exhibition of them in 1961 in Washington DC.

The Taos News wrote in 1960, “Mrs. Cata who spoke here last spring at the New Mexico State Folklore convention is famous among other things for her dolls“. The Albuquerque Journal wrote in 1953, “Mrs. Regina Cata from San Juan, dolls are internationally known for their beauty of treatment and authenticity of styling. Each doll is dressed in miniature turquoise jewelry, narrative hair styling, buckskin leggings, and hand made blankets.“. And as early as 1938, the Santa Fe New Mexican wrote, “The Indians of the Espanola valley villages have sent exhibits to Gallup for the ceremonial. Particularly noticeable was the collection of dolls made by Mrs. Regina Cata wife of the governor of San Juan Pueblo.”

The Sante Fe New Mexican wrote on April 30, 1961, about Regina Cata:

“…”In the 55 years of marriage, she never participated in the tribal dances nor did she ever wear Indian dress and seemed surprised that the question was put to her. “Why?” There was no need she exclaimed obviously satisfied with her strong identity. However she felt deeply the decline of the arts in her adopted pueblo. “I felt sad to see San Juan pueblo fall behind in leadership and in the arts. Pottery making was dying out and ceremonial dress was becoming scarce because pueblo Indians were buried in their outfits” the former board member of the Santa Fe Museum explained.” …..”So, in 1930after teaching in the Santa Fe Indian School for 17 years, the mother of ten surviving children out of the 20 she had borne, returned with them to her husband’s pueblo to live. There she taught in the San Juan Day School and in 1930 with the permission of her superintendent sought to “revive the arts”. Telling of the project, the usually contained woman spoke with passion stressing that the main purpose was revival and not to “copy or borrow” from others. She believed that San Juan Pueblo had a lot to offer. To prove it she dug in “Fi Ogay” an old pueblo north of Alcalde for potshards with markings, and she used them for patterns. To support the revival program she held bazaars. In spite of this the revival attempt failed- the sewing, pottery, wearing, emberidery. “The young people were interested in the new way of life outside the pueblo- movies, ball games, there were too much activity and no interest she said. Bitterly disappointed, in 1936 she returned to work alone. Since then she has made pottery, clay busts and masks, embroidered cloches and hundreds of dolls depicting many tribes.”