Charles Loloma (1921-1991) was born in Hotevilla on Third Mesa of the Hopi Reservation. From 1941 to 1945 he served in the army, spending over three years in the Aleutians. He married Otellie Pasivaya in 1942. Immediately following his discharge, they settled in Shipaulovi on the Second Mesa. Late in 1945, the GI Bill made it possible for him to begin studies in ceramics at the School for American Craftsmen at Alfred University, in Alfred, New York. There he received a fellowship from the Whitney Foundation for research in ceramics on the Hopi Reservation. He worked on this project from 1949 to 1951. In 1954 he and his wife opened a pottery shop in Scottsdale, becoming the first tenants of the successful Kiva Craft Center, founded by Lloyd Kiva New.

It was in 1955 that Loloma began turning his creative efforts toward jewelry, and gradually this new art form took precedence over the popular Lolomaware pottery line. During the six-year period he had the shop, he devoted his time to teaching at the University of Arizona in Tucson, at Arizona State University in Tempe, and at their summer extension courses in Sedona, AZ. In 1959 he took part in the initial conference, which launched the Rockefeller Foundation’s Southwest Indian Art Project at the University of Arizona, and was an instructor for its three succeeding summer sessions. In 1962, with the founding of the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe came the realization of a long time dream he had shared with Lloyd New, a school directed toward helping Indian students find an individual expression of their cultures through the arts. Loloma and New were appointed heads of the Department of Plastic Arts, as well as the Sales Department where student work was sold.

Loloma’s jewelry became internationally known and pieces can be found in the collections of many distinguished persons, including Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Mrs. Frank Lloyd Wright. In the 1960′s, President Lyndon B. Johnson commissioned pieces to be presented to the Queen of Denmark and the wife of the Philippine president. During the sixties, Loloma won First Prize seven years in a row at the Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition.

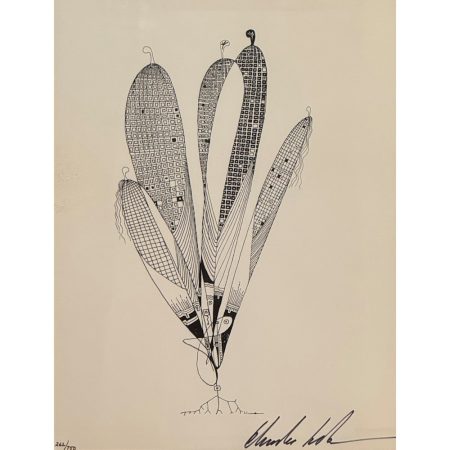

Loloma maintained a deep reverence for Hopi beliefs and the ceremonies. He lived by the Hopi calendar, its cycles of birth, death, and regeneration. In autumn, the fields behind his studio were filled with ripening squash and melon, and on the crest behind it, he was found with relatives roasting corn to provide for the winter ahead. There is a seeming disparity between this way of life and the sophisticated world in which he moved. His answer to this was: “We are a very serious people and have tried hard to elevate ourselves, but in order to create valid art, you have to be true to yourself and your heritage”. He also said: “I felt a strong kinship to stones, not just the precious and semi-precious stones I use in my jewelry, but the humble stones I pick up at random while on a hike through the hills or a walk along the beach. I feel the stone and think, not to conquer it, but to help it express itself”. Charles Loloma passed away in 1991.