Collector's Corner

CONTROVERSY: Unexpected Subject Matter in Inuit Art

It is said that controversy sells. However, in the case of Indigenous art, particularly Inuit art, the opposite has ben true. Generally speaking, Inuit artists have “played to the market.” Keenly aware that the art market has wanted colorfully appealing works, rather than disturbing ones, that is what has, for the most part, been created. However, there have been and continue to be exceptions. Works dealing with a diverse range of controversial themes have been produced and, more importantly, collectors began acquiring them, often to the surprise of artists and gallery owners alike. Increasingly, no topic is off limits to Inuit artists. Physical and sexual abuse, violence, autoeroticism, and cannibalism are just a few of the subjects Inuit artists have explored.

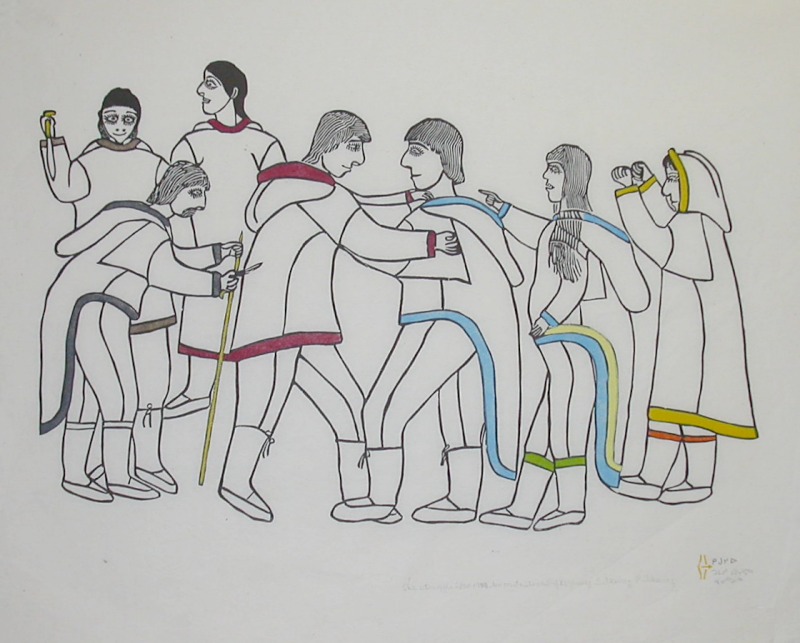

Trading Women for Supplies by Napachie Pootoogook, Ink, Inuit, Cape Dorset,20” x 26” (1997/98). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

Translation of the artist’s Inuktitut incription: “The captain from the bowhead whale hunting ship is trading materials and supplies for the woman. As usual, the man agrees without hesitation.”

Trading Women for Supplies, a drawing by Napachie Pootoogook, documents the sexual exploitation of Inuit women by men – Inuit and non-Inuit. The subject of women being traded between men for supplies was clearly troubling to Napachie Pootoogook who created a number of drawings as well as a print on the subject. In a 1991 interview Napachie stated, “As for the historic scenes, I have not actually seen them. I used to know some half Inuit a long time ago and I heard tales . . . . I heard that the men used to trade their wives for some kinds of things – like tobacco or other things, with the white sailors. That is why there are half Inuit – it’s because the sailors used to want women for an exchange of things even when or if a woman had a husband.”

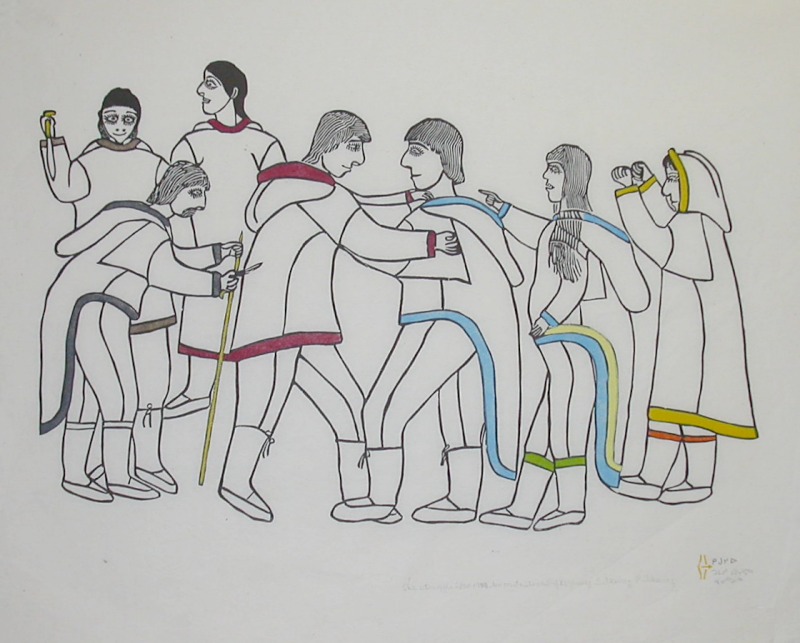

Male Dominance by Napachie Pootoogook, ink & colored pencil, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 26” x 20” (1995-1996). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

Translation of artist’s Inuktitut inscription: “Aatachaliuk is scaring women to ensure his domination, before he claims them as wives, after slaying his male enemies. He did this to hide his soft side.”

The subject matter of Napachie Pootoogook’s Male Dominance is even more shocking: a man has murdered the husbands of five women so he can claim them as his own. The man looks out from the page with a self-satisfied smile while the women, who are connected to each other and to the man by a rope, are clearly frightened and grief-stricken. Inuit women were frequently abducted against their will to become a man’s wife. If a female was already married a man would simply kill her husband and claim her as his own. Considering the vast expanses and harsh environment of the Arctic, there wasn’t much a woman could do. If she resisted or rebelled, she was subjected to beatings. Women were at the mercy of men and all they could do was to hope for the best.

Comingto Take a Wife by Janet Kigusiuq, pencil crayon, Baker Lake, 12½” x 16” (2002) Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

Like Napachie Pootoogook, Janet Kigusiuq tackled the subject of women being take for wives against their will in her drawing Coming to Take a Wife. The choice of the word take combined with the drawing’s imagery is very telling: a man is clearly taking a woman by force while a third person tries to prevent the abduction. Rarely, if ever, did an Inuit woman get the husband she wanted; the choice belonged solely to the man. Women were often kidnapped and taken far from their families. There was little choice except to submit to the man who had abducted them.

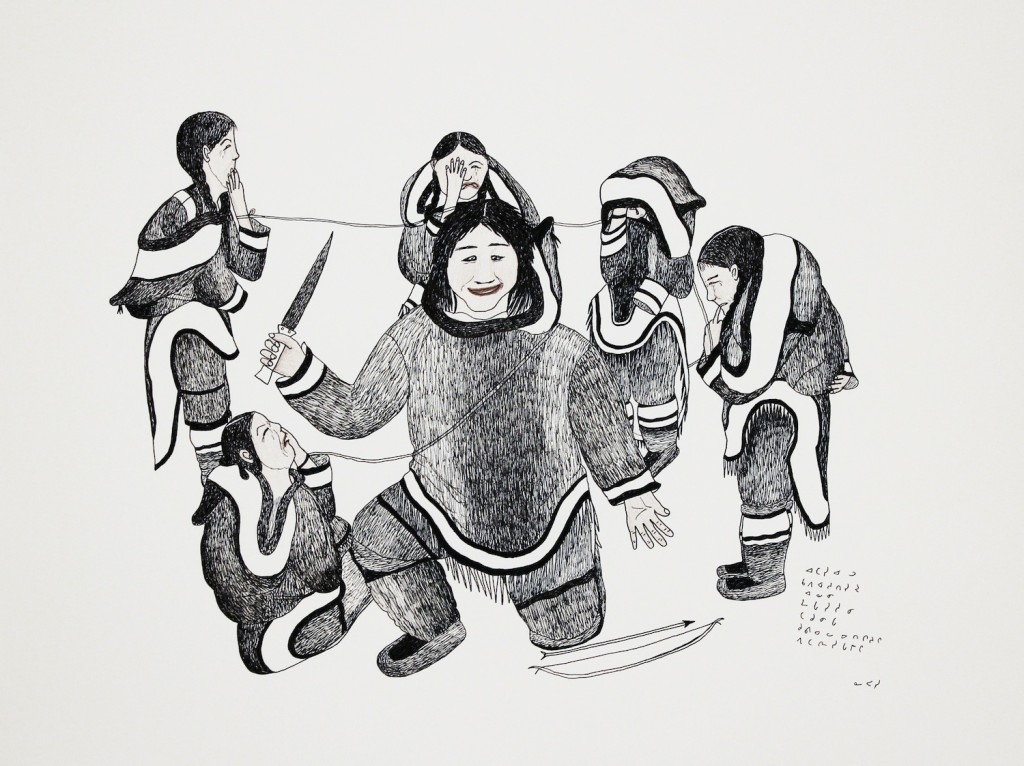

Vengeance by Peter Aliknak, stonecut, 44/50, #28, Holman Island, 17¾” x 24¼” (1972). Donated to the Brooklyn Museum from the Edward J.Guarino Collection in 2013. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

The violence in Peter Aliknak’s Vengeance, one of the most shocking Inuit prints ever produced, is palpable as it captures a horrific moment in time – a knife wielding man in the act of stabbing another man. The intended victim has fallen backwards as a third man attempts to pull him out of harm’s way. This is a life and death struggle and the viewer is left to wonder if the man has been killed or if he has narrowly escaped with his life. Of the three figures the artist chose only to show the face of the man holding the knife. Except for the knife and the expression on the face of the attacker, the work has a casual, matter-of-fact documentary-like quality.

The Struggle by Janet Kigusiuq, Inuit, Baker Lake, #19, Linocut & Stencil 1/30, edition 30, 19¾” x 24½” (1980). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of The Upstairs Gallery, Winnipeg.

Although she was known for her scenes of traditional Inuit life and her abstract works, Janet Kigusiuq did produce a number of works that depicted the darker aspects of her culture. In The Struggle she portrays a communal conflict. The central figures of the work are two men who are fighting. However, those on the left side of the print are somewhat puzzling. Behind the combatant on the left is a man who is hunched over and is holding a stick in one hand and and a knife in his other hand with which he is about to stab one of the fighters in the back. Behind him is a man who also wields a knife. It is a shocking and disturbing scene. As in all cultures, there is competition among men over women and between women over men, which often leads to violence. This may, in fact, be what is depicted in this print. Janet Kigusiuq has created a scene fraught with drama and the viewer is left pondering what exactly is taking place. Is one man trying to steal another’s wife? Has an act of adultery taken place or one of rape? The situation is serious enough that others in the community have become involved in the conflict.

The Student by Jamasie Pitseolak, Inuit, Cape Dorset, hand painted dry-point etching, 2/15; paper size: 31.5” x 44;” image size: 23.5“x 35“(2010). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver.

The Day After by Jamasie Pitseolak, Inuit, Cape Dorset, hand painted dry-point etching, 2/15; paper size: 19.5” x 15;” image size: 11.75“ x 8.5 “ (2010) Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver.

Two of the most shocking and disturbing contemporary works on paper by an Inuit artist were produced by Jamasie Pitseolak: The Student and The Day After. These two prints, which form a whole, are the result of what happened to the artist while a student in the Canadian Indian residential school system. This was the first time that this topic had been addressed in any Inuit artwork. The Student, the first of the print pair, shows a boy (the artist) in a bathtub just prior to being abused by one of his teachers who stands beside the tub. Strong marks over the image of the attacker are employed as if to cross him out. The Day After, the second print, shows the aftermath of the attack. A star and other markings emerge from the attacker’s mouth, representing expletives and threats, as they do in comic book art. The student, almost formless and looking much like a limp pink rag, is held by his neck near the teacher’s desk. Both The Student and The Day After are a far cry from what collectors expected with regard to Inuit art, but they reflect another aspect of the Inuit experience.

Autoerotic Asphyxia by Pitseolak Qimirpik, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Sculpture in stone, antler, artificial sinew, 8” x 6” x 2” (2021). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto..

For most collectors of Inuit art Pitseolak Qimirpik’s Autoerotic Asphyxia would probably be a bit of a hard sell. In terms of Inuit art, the image is atypical and shocking. Visually, it is not terribly difficult to figure out what the figure is doing. However, the question becomes why? Erotic asphyxiation, whether practiced solo or with another person, is probably not part of the average collector’s sexual repertoire. Erotic asphyxiation is employed in the belief that the restriction of oxygen heightens sexual arousal and pleasure. One should not assume that it is something the artist practices. He might have become aware of this fetish via TV, movies, or the Internet – all available in the Arctic. It is also possible that the artist knew of someone who died as a result of autoerotic asphyxia, a common result of this practice. However, why the artist created this work remains a mystery.

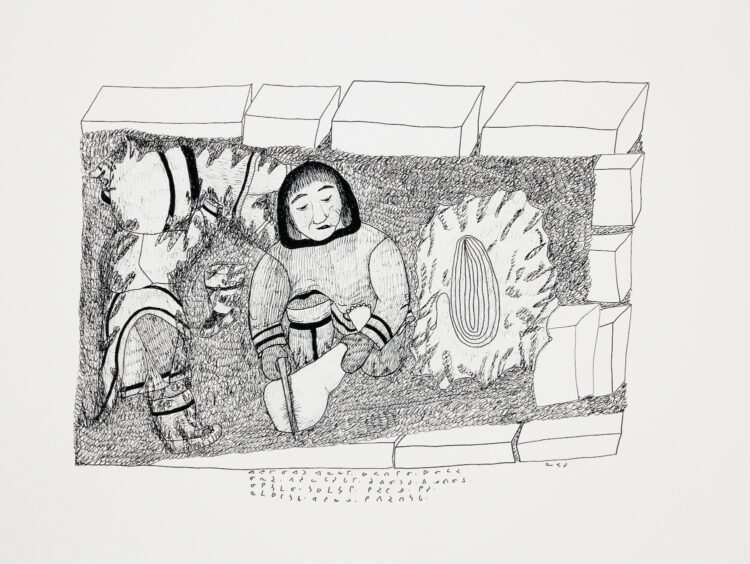

Composition (Eating His Mother’s Remains) by Napachie Pootoogook, ink, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 20” x 26” (1999-2000). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto..

Translation of artist’s Inuktitut inscription: “He is chopping up and eating his mother’s rump before leaving. He is also preparing to take the human remains by wrapping them in seal skin and using the rope to bind it.”

For many viewers, Composition (Eating His Mother’s Remains) is arguably the most shocking Inuit artwork they have ever seen. However, Napachie Pootoogook has taken a potentially explosive subject and handled it with sensitivity. Cannibalism has been practiced around the world throughout human history for varying reasons and it is considered to be the ultimate taboo. It was not part of Inuit cultural practice and when it did occur it was the result of prolonged famine. Although this was not something the artist knew of personally, it is more than likely that she was told about this particular man by someone who had first hand knowledge of this incident.

Many collectors believe that controversial subject matter has no place in Indigenous art, particularly Inuit art, and some of the harshest criticism faced by Indigenous artists has come from members of their own communities who feel that problems should not be aired publicly. In spite of this, Inuit artists, in particular, continue to create works that explore shocking and painful themes. They refuse to remain safely within the status quo, only doing what is commercially viable. They are to be commended.