-

×

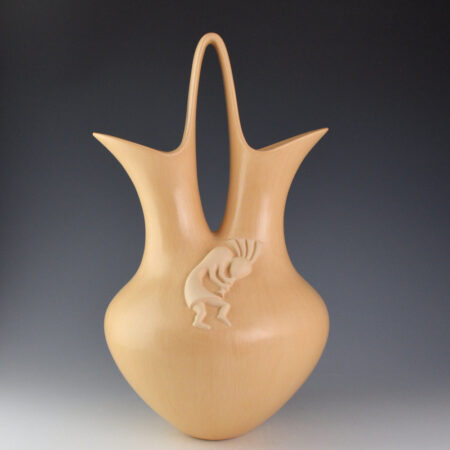

Qoyawayma, Al - 15" Wedding Vase with Flute Player (1987)

1 × $ 6,000.00

Qoyawayma, Al - 15" Wedding Vase with Flute Player (1987)

1 × $ 6,000.00 -

×

Askan, Linda & Diana Halsey - Storyteller with Plate (2 Pieces)

1 × $ 200.00

Askan, Linda & Diana Halsey - Storyteller with Plate (2 Pieces)

1 × $ 200.00 -

×

Cain, Mary and Keith Tanin - Bowl with Carved Avanyu

1 × $ 250.00

Cain, Mary and Keith Tanin - Bowl with Carved Avanyu

1 × $ 250.00 -

×

Chavarria, Denise - Jar with Mountain, River, and Cloud Designsk

1 × $ 150.00

Chavarria, Denise - Jar with Mountain, River, and Cloud Designsk

1 × $ 150.00 -

×

Borts-Medlock, Autumn - Red Clay Fox - Sitting (2025)

1 × $ 2,000.00

Borts-Medlock, Autumn - Red Clay Fox - Sitting (2025)

1 × $ 2,000.00 -

×

Patricio, Robert - "Rain at Dusk" Swirling Clouds Jar

1 × $ 2,000.00

Patricio, Robert - "Rain at Dusk" Swirling Clouds Jar

1 × $ 2,000.00 -

×

Patricio, Robert - "Pixelated" Four Color Water Jar

1 × $ 1,800.00

Patricio, Robert - "Pixelated" Four Color Water Jar

1 × $ 1,800.00 -

×

Archuleta, Anna - Bowl with 16 Carved Melon Ribs

1 × $ 350.00

Archuleta, Anna - Bowl with 16 Carved Melon Ribs

1 × $ 350.00 -

×

Patricio, Robert - "Chocolate Jar" with Rain Designs

1 × $ 600.00

Patricio, Robert - "Chocolate Jar" with Rain Designs

1 × $ 600.00 -

×

Archuleta, Mary Ester - Red Flat Top Bowl with Carved Avanyu (1960s)

1 × $ 1,400.00

Archuleta, Mary Ester - Red Flat Top Bowl with Carved Avanyu (1960s)

1 × $ 1,400.00

Collector's Corner

MISCELLANY: Various and Sundry Works by Rick Bartow

Although some consider the expression various and sundry to be a redundancy, others say that it is not since the two words do not, in fact, have the same meaning. They claim various means “varied” while sundry means “of an indeterminate number.” The term does have a nice ring to it, however, and it certainly fits the creative output of Rick Bartow whose work was certainly varied and, since he was so prolific, it is doubtful if anyone actually knows the exact number of pieces he created.

Knowing my fascination with all things Bartow, Charles Froelick, owner of the Froelick Gallery in Portland, Oregon, frequently sends me images of little known Bartow works that always pique my interest. I am often sent images of works that fit a particular theme (i.e. Bartow’s totem animals) or represent a large area of influence on his art such as ukiyo-e prints. At other times, Charles Froelick emails me a disparate mix of pieces that reflect Rick Bartow’s many interests. That was the case recently when an email contained images of Rick/Julie/?, Indians: Chief Joseph, Yaqui Deer Dancer, and Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Oaxaca.

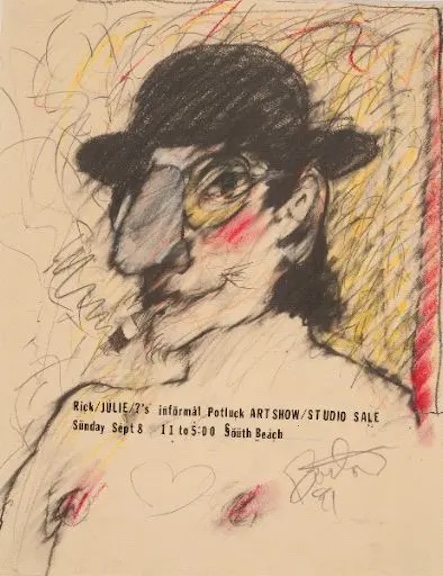

Rick/JUILIE/?’s informal Potluck ART SHOW/STUDIO SALE by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, pastel, charcoal, letter transfer, graphite on paper, 12” x 9” (1981). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

As it turns out, the actual title for Rick/Julie/? is quite long: Rick/JUILIE/?’s informal Potluck ART SHOW/STUDIO SALE. I never know what will attract me to a particular work of art and sometimes the reasons I find a particular work interesting are often downright bizarre. In the case of Rick/JUILIE/? the work intrigued me because, visually, it had the look of something you might see in a German cabaret prior to WWII.

In this work, Bartow presents himself in a bowler hat, smoking a cigarette, his large nose and iconic eyeglasses prominent. He is bare chested, his nipples a bright pink and between them he has drawn a heart. He appears to be looking slyly out at the viewer. Around his image he as made a variety of lines and squiggles, which he referred to as mark making. He also signed and dated the piece on the lower part of the page near one of the figure’s nipples. In addition to writing, “Rick/JUILIE/?’s informal Potluck ART SHOW/STUDIO SALE” across the chest of this self-portrait, Bartow also wrote the day of the week, the date, the time and the place of the sale: “Sunday September 8 11 to 5:00 South Beach.”

For some background information on this work, I emailed Charles Froelick, my source for all things Bartow:

In 1979 Rick got sober, he stopped burning his art then, and he began committing serious attention to making art. This unique drawing . . . is from 1981, among the earliest years of Rick’s career. This is also the first exhibit poster that I am familiar with Rick making, and he went on to make promotional posters for many shows over the decades. The early 1980s are when Rick began to focus seriously on making art, and his new relationship with Julie Swan blossomed. Julie was an artist, a basket weaver, they were both musicians – they began playing music together with friends in Newport. Julie was among Rick’s strongest supporters. She helped give Rick confidence in his artistic voice, and she encouraged him to treat his art professionally! They showed their art in various community spaces and commercial gallery exhibitions on the Oregon coast and Willamette Valley, and they knew how to make other selling opportunities happen . . . such as this ‘pot luck’ event. Rick knew the importance of working with galleries because that gave him more time in the studio . . . .Even after he began exhibiting internationally, he still made posters that celebrated the galleries. His posters always included combinations of drawn and painted imagery . . . with text – sometimes stenciled, stamped or handwritten gallery names and details, Maori words, Japanese calligraphy, old German script, journal entries and text fragments . . . .

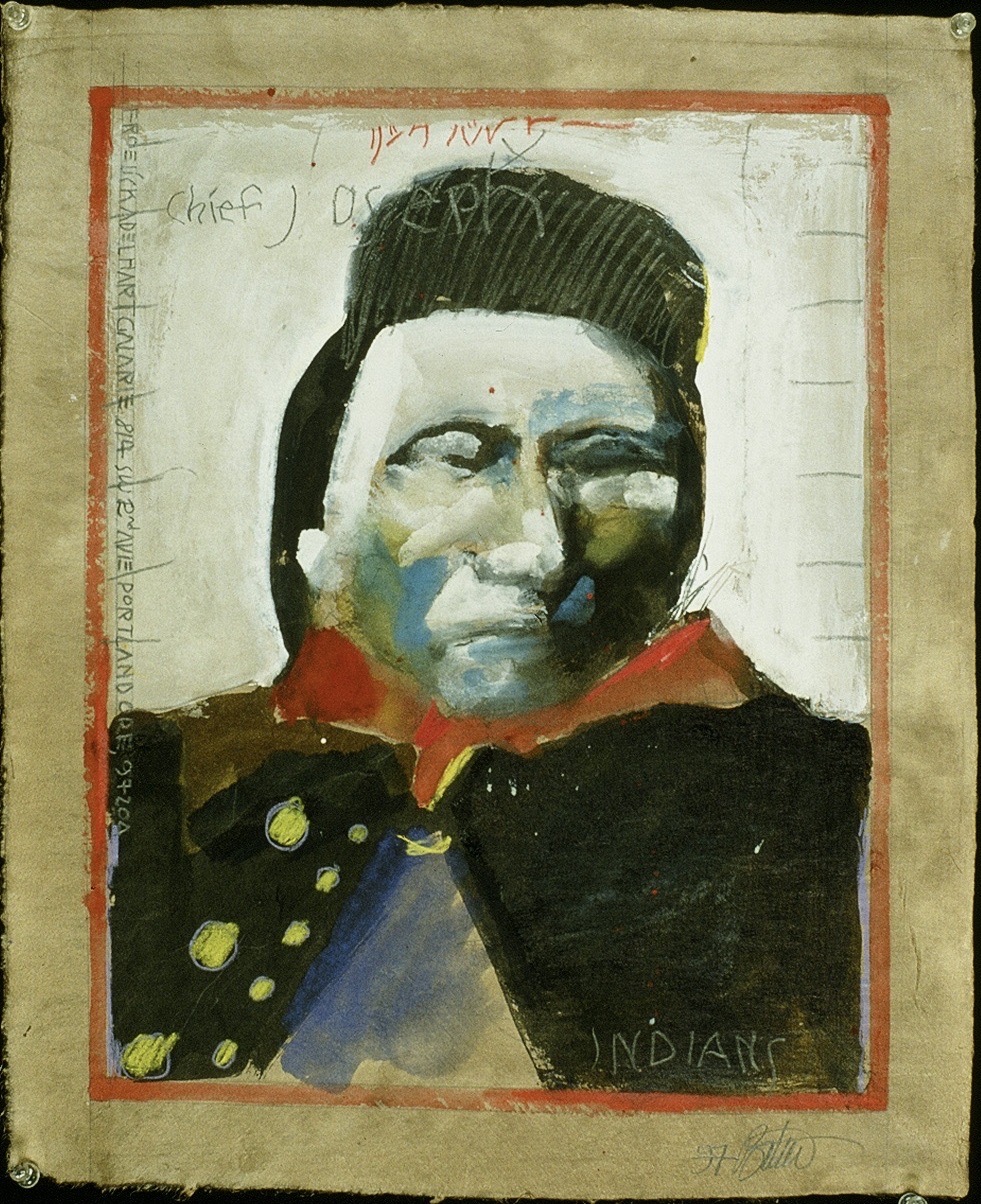

Indians: Chief Joseph (Poster) by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, mixed media on nao paper, 19” x 16” (1997). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Chief Joseph was one of the leaders of the Wallowa band of the Nez Perce Tribe. He became much admired for leading his people on an heroic flight across the Rocky Mountains in 1877. When pressured by the U. S. Government abandon their homeland in Oregon and join the other Nez Perce in Idaho, the Wallowa band refused. Violence broke out and, with the U.S. Cavalry in pursuit, the Wallowa band fled across the Bitterroot Mountains to Montana where they hoped to reach eventual safety in Canada. The tribe was decimated by constant fighting as they fled and Chief Joseph finally surrendered only forty miles from the Canadian border. At the time of surrender in 1877, many of the Wallowa Nez Perce had fled to the hills; they had no food or blankets and were freezing. When he gave up, Chief Joseph said, “I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my Chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.” The Wallowa were taken to a reservation in Oklahoma, then known as Indian Territory, and finally were sent to the Colville Reservation in what is today North Central Washington State. Chief Joseph made a number of trips to Washington, D.C. to plead for a return of his tribe to their homeland, but to no avail. He died in 1904 of what the doctor attending him said was “a broken heart.”

Clearly, the figure of Chief Joseph meant a great deal to Rick Bartow since he depicted him so lovingly. Looking pensive and sad, Chief Joseph wears a dark U.S. Cavalry jacket with a red collar scarf and prominent yellow buttons. The jacket is open, revealing a patch of blue shirt. Chief Joseph does not meet the viewer’s gaze, but appears to be looking at something only he can see. Around the image, Bartow painted an artificial frame. Within it he has not only included an image of Chief Joseph, but written information as well. At the top of the page, in red, are Japanese characters. Below and beginning slightly to the left are the words Chief Joseph, which continue into the figure’s hair. Along the the left side of the frame, Bartow has written, “Froelick Adelhart Galerie [sic]” as well as the gallery’s address. On the lower right of the page, Bartow wrote, “INDIANS,” which refers to a series he created, and below this, on the “frame” he signed his name.

Yaqui Deer Dancer (Poster) by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, mixed media on handmade paper, 31” x 13” (1997). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Rick Bartow traveled to Mexico and his work was exhibited in Guanajuato in 2002 and Oaxaca in 2005. Clearly, he was inspired by the experience. The Yaqui, a Native American tribe that inhabits parts of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, perform a ritual known as the Deer Dance in which participants wear masks and antlers and also carry rattle sticks and wooden staffs. The regalia worn by the dancers represents a transformation, a theme that is a fundamental part of Rick Bartow’s art. Much of the imagery in his work depicts humans becoming animals or the other way around. Understandably, Bartow was fascinated with the spiritual idea of transformation expressed in cultures outside his own Wiyot traditions. In a sense, through their ritualized movements the dancers become deer, a sacred animal among the Yaqui. In this way, they are able to commune with their spirit guides. One of the purposes of the Deer Dance is to honor the deer spirit and to ask for its blessing during the hunt. In Yaqui belief, the deer represents all that is good. Through the dance, the story of the deer and the flower world is told. In that spiritual realm, all animals are the friends of humans. When a deer, whom the Yaqui refer to as “Little Brother, is sacrificed it is thanked for giving up its life so that the Yaqui might live.

Yaqui Deer Dancer was the basis for a poster for an exhibit at the Yanagisawa Gallery in Urawa City, Saitama Prefecture, Japan. Bartow wrote the galleries contact information on the lower part of the page under the image. Along the left side of the page he wrote the work’s title and also placed his two personal chops. At the very top of the page there are Japanese characters and the name Bartow written in capital letters. Once again, Bartow used a “framing device” to contain the image and the information he wanted to publicize.

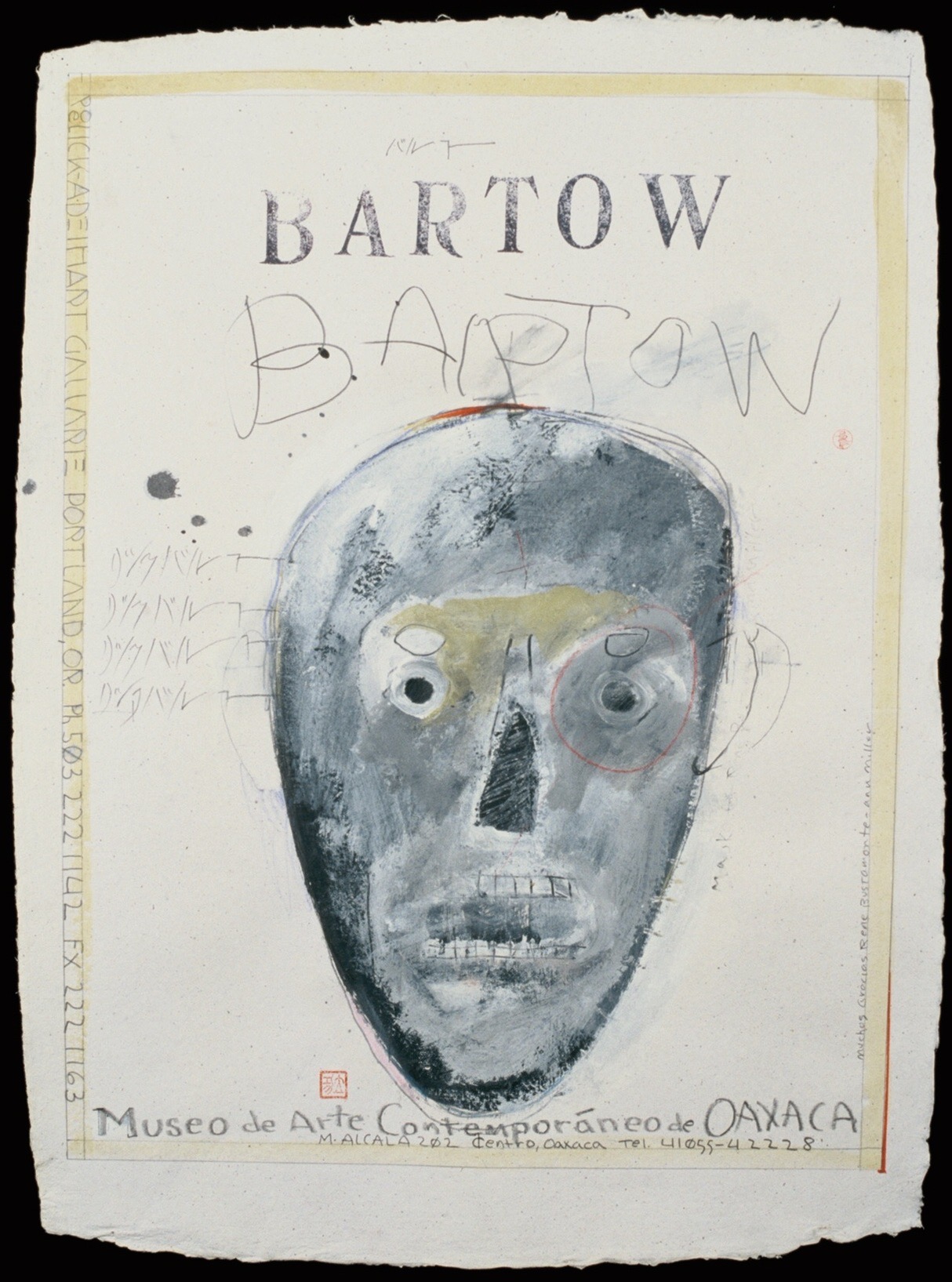

Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Oaxaca by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, mixed media on paper, 30” x 20” (1999). Image courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

The city of Oaxaca produced three of Mexicos most important artists of the 20th century: Rufino Tamayo, Rudolfo Morales, and Francisco Toledo. Considering his admiration for the work of other artists, it is more than likely that Rick Bartow visited the Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Oaxaca (MACO), especially since the museum was founded based on the wish of Tamayo and established by Francisco Toledo. MACO has collections of sculpture, painting, ceramics, photography, and graphic design and presents permanent & rotating exhibitions of contemporary Mexican art.

Bartow would also have been well aware that the City of Oaxaca is surrounded by important archaeological sites such as Monte Albán, Mitla, Zaachila, Yagul, Dainzú, and Lambityeco to name a few.

With the importance of masks and transformation in his own work, a Mexican mask is not unexpected in a work Bartow produced in honor of the Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Oaxaca. Exhibited at the Froelick-Adelhart Gallery, Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Oaxaca features a single, striking image: a skeletal mask drawn in tones ranging from grey to black with a yellowish section between the staring eyes and a mere hint of red at the very top of the skull.

In addition to the name and address of the Froelick-Adelhart Gallery, written within the work’s “frame,” Bartow also wrote “Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Oaxaca” and the museum’s address below the mask and this time only used one of his personal chops – the square one. On the left side of the mask there are four lines of Japanese characters and on the right side Bartow has drawn what appears to be the outline of an ear, making the image of the skull darkly humorous. Above the mask is the name Bartow done three ways: first is Bartow’s signature; under it is a stenciled version done in capital letters; and below that the name is also printed in capital letters. The work also includes ink splotches and what appear to be stray marks on the paper, but anyone who is familiar with Rick Bartow’s work would be well aware that they are all part of his “mark making,” an integral part of his art. In a poem, Bartow wrote the following: “I pull the marks up and use them like fish to feed my imagination. The marks are sometimes pieces to a puzzle, solutions to little mysteries that signal the completion of an image.”

Rick Bartow’s art always takes me on an intellectual journey. Over the course of many years, I have been intrigued by the artist’s images of animals; his erotic works; the mysteries contained within one particular piece; the influence of Japanese prints; depictions of various artists and musicians; references to literary works; and, of course, Bartow’s unique take on the concept of transformation as well as his use of mark making. Rick Bartow’s body of work is deeply rich and varied. Not only is it visually bold, it is also endlessly fascinating. Whenever I encounter a Bartow work that is new to me, down the rabbit hole I go into an exciting and mysterious adventure.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Charles Froelick, owner of the Froelick Gallery, for his invaluable assistance with

Qoyawayma, Al - 15" Wedding Vase with Flute Player (1987)

Qoyawayma, Al - 15" Wedding Vase with Flute Player (1987)  Askan, Linda & Diana Halsey - Storyteller with Plate (2 Pieces)

Askan, Linda & Diana Halsey - Storyteller with Plate (2 Pieces)  Cain, Mary and Keith Tanin - Bowl with Carved Avanyu

Cain, Mary and Keith Tanin - Bowl with Carved Avanyu  Chavarria, Denise - Jar with Mountain, River, and Cloud Designsk

Chavarria, Denise - Jar with Mountain, River, and Cloud Designsk  Borts-Medlock, Autumn - Red Clay Fox - Sitting (2025)

Borts-Medlock, Autumn - Red Clay Fox - Sitting (2025)  Patricio, Robert - "Rain at Dusk" Swirling Clouds Jar

Patricio, Robert - "Rain at Dusk" Swirling Clouds Jar  Archuleta, Anna - Bowl with 16 Carved Melon Ribs

Archuleta, Anna - Bowl with 16 Carved Melon Ribs  Patricio, Robert - "Chocolate Jar" with Rain Designs

Patricio, Robert - "Chocolate Jar" with Rain Designs  Archuleta, Mary Ester - Red Flat Top Bowl with Carved Avanyu (1960s)

Archuleta, Mary Ester - Red Flat Top Bowl with Carved Avanyu (1960s)