Collector's Corner

REMEMBRANCE OF ACQUISITIONS PAST: How the Work of Rick Bartow Entered My Collection

As a collector, I have very few regrets. One of my biggest, however, is never having met Rick Bartow. From the very first time I encountered the artist’s work in 2003 as part of Continuum: 12 Artists at the National Museum of the American Indian in Manhattan I knew that I was seeing something important. I became determined to learn as much as possible about the artist and his work. Fortunately, the wall texts indicated that many of the paintings on view were on loan from the Froelick Gallery in Portland, Oregon, a city I was scheduled to visit in a few weeks. The works on paper by Rick Bartow that I acquired on that trip were the first to enter my collection and I was off and running.

In 2012, Andrea Hanley, currently Chief Curator at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, arranged for me to meet Mr. Bartow at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. during the weekend that a new sculpture by the artist was scheduled to be dedicated. It was to be a weekend filled with many events relating to the artist and his work. Alas, meeting Mr. Bartow was not to be. On that same weekend the son of a very dear cousin was getting married and there was no way I could miss this family affair. Italians have a saying: La Famiglia e tutto (Family is everything.). And they mean it. Actually, it is more of a commandment than a saying, but you get the idea.

I had hoped to meet the artist, at last, in August 2016 when Rick Bartow: Things You Know But Cannot Explain, a touring retrospective exhibition of the artist’s work, opened at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe. Sadly, that meeting was not to be either. Rick Bartow died on April 2 of that year. He was one of our country’s greatest contemporary artists and more than ever, I feel that this artist’s work is among the most important in my collection.

Over the years, I have managed to add two sculptures and a small painting by Mr. Bartow to my collection, but I have particularly focused on the artist’s drypoint etchings, which I consider among his most important creations. It is difficult, if not impossible, to choose favorites from among the thirty-seven Bartow prints in my collection, but there are some that have made an indelible mark on my heart for a variety of reasons: Yanagissawa Hawk 100, Salmon Boy, Goro Kakei, Grumpy, and CH Crow.

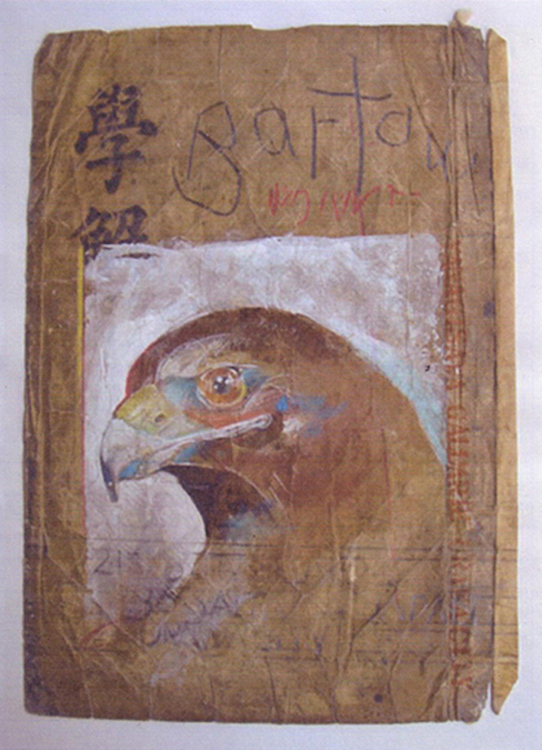

Yanagisawa Hawk 100 by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, multimedia: gouache, pencil and graphite on handmade paper, painting/drawing, 9”w x 13”h (1997). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Yanagissawa Hawk 100 is the first work on paper by Rick Bartow that I added to the collection. I acquired it on my initial visit to the Froelick Gallery. I arrived feeling unwell and the staff immediately brought me a chair and a cool glass of water. When I was feeling better they brought me a range of Rick Bartow’s works to consider, which quickly gave me an idea of the artist’s output. Although I was new to the gallery, Charles Froelick and his staff treated me as if I were a visiting potentate and I have never forgotten their kindness. Since I couldn’t afford one of Bartow’s large-scale paintings and, even if I could, they were too large for my apartment, the gallery’s staff suggested I focus on the artist’s works on paper. Yanagisawa Hawk 100, a multimedia piece, immediately caught my attention. I was not only drawn to the powerful image of a hawk, but I was also intrigued that the artist had combined gouache, pencil, graphite as well as painting, drawing and writing on handmade paper.

Over the years, I learned that Rick Bartow often employed images of hawks as a stand-in for himself in his work. In this case the artist having written his name above the hawk and the red printing underneath, which is the artist’s name in Japanese, reinforces that idea.

The word Yanagisawa in the title refers to the Yanagisawa Gallery in Saitama City, Japan where the artist had his first solo exhibit in 1994. It is believed that this unique mixed-media creation was most likely made for “Drawings: Flowers and Animals,” a 1997 exhibit at the Yanagisawa Gallery. The kanji characters in the work were already on the paper when it was given to the artist by Japanese printmaker Seiichi Hiroshima. Also curious is the use of 100. Bartow often non-sequentially numbered his pieces, but these designations do not refer to the total he has produced on a specific subject. There seems to be no apparent system to the numbering so Yanagisawa Hawk 100 might be the fifth hawk image the artist had created or the fiftieth. It is just a way of identifying a particular work.

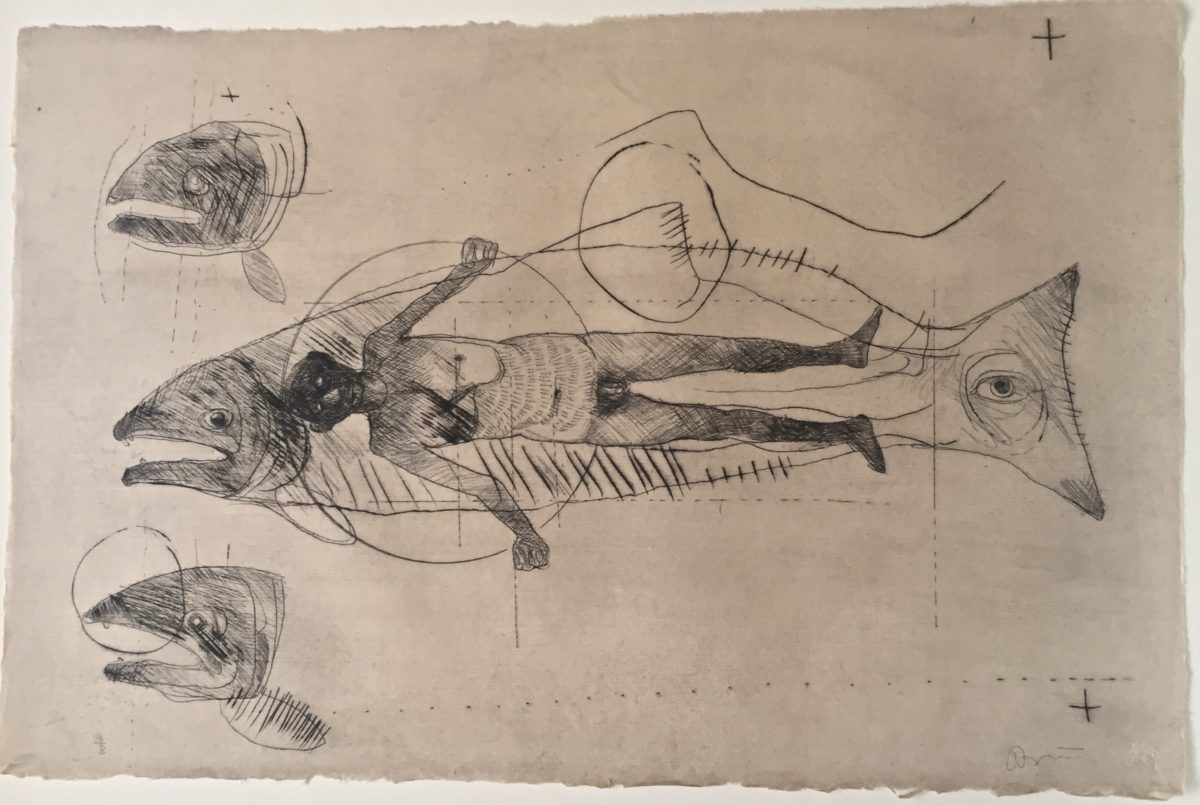

Salmon Boy by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint on handmade Matsumata paper, ed. 4/8, 15″ x 22” image and paper, (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

One day in August 2016 I arrived at the Froelick Gallery as the staff was beginning the process of installing Sparrow Song, an exhibit of paintings, sculptures, and prints by Rick Bartow. When I saw Salmon Boy, a print that was framed and lying against a wall, waiting to be hung, all I can say is that it was the collector’s version of love at first sight. As soon as I saw it, I decided that, if I could afford it, I would definitely add it to my collection. Charles Froelick explained that the year before the artist “scratched/drew . . . three drypoint images with skeletal images inside . . . . but they were not editioned until winter 2016.” He also added that, at that point, Bartow was barely speaking.

Salmon Boy is quintessential Rick Bartow. It is both surreal and deeply symbolic. It is clear that when the artist produced this work he was keenly aware of his own mortality. The print contains images of severed fish heads and a boy, perhaps a corpse, superimposed over a somewhat skeletal salmon. One side of the boy’s chest appears to be scratched out and he holds a circle. In this way, the artist associates the transience of human life with that of the salmon, which hatches, travels to the vast oceans where it spends a good part of its life, then, against great odds, travels upstream to its place of origin to spawn and finally die as the cycle begins again. In the salmon’s tail is an eye. It is a symbol that the artist has used in many works. Although it may suggest the All-Seeing Divine, it could just as easily represent the ability of artists to perceive aspects of existence that are closed to the rest of us.

|

|

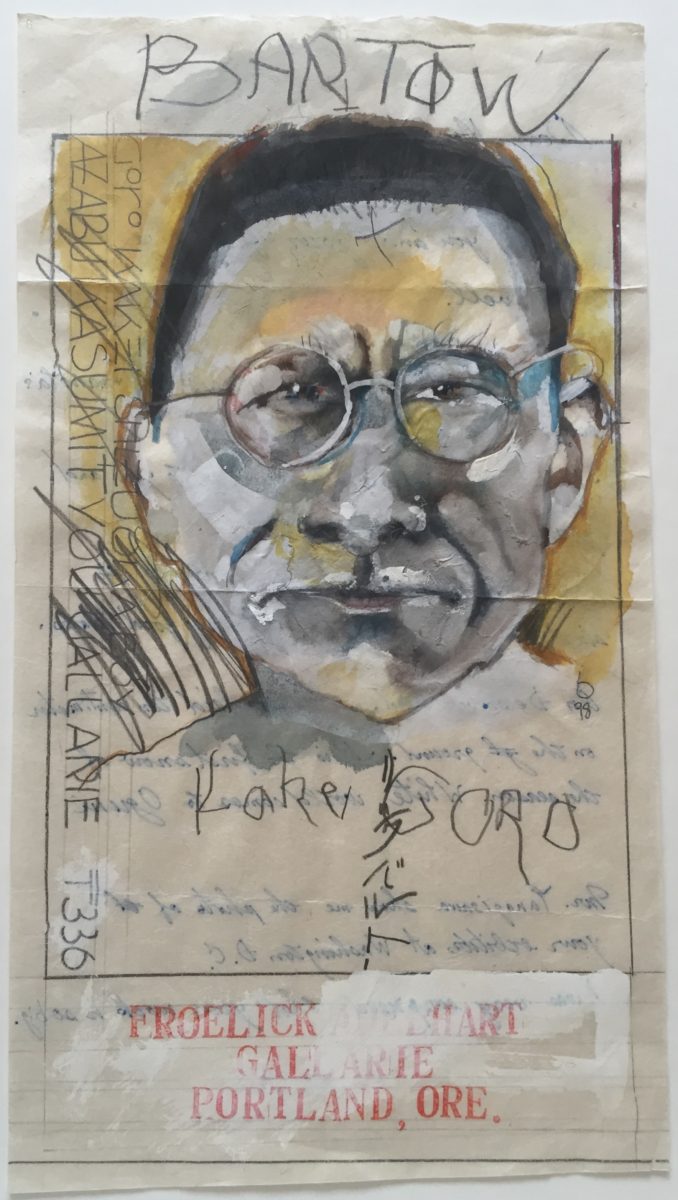

Goro Kakei by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, multimedia on paper, image: 14”x 8”; paper: 14” x 8” (1998). Note: There is a self-portrait by the artist on the reverse side as well as a personal note. Collection of E. J. Guarino.

On that same 2016 visit I acquired Goro Kakei, which turned out to be a revelation and a mystery. I had chosen the piece because I found the strong features of the portrait an interesting contrast to the delicacy of the colors utilized and the type of paper chosen. As I was looking at the work, I just happened to turn it over and, to the surprise of everyone present, on the reverse side was a self-portrait of the artist, plus an unsigned handwritten note. The piece instantly became an artistic mystery, which Charles Froelick and I were determined to solve.

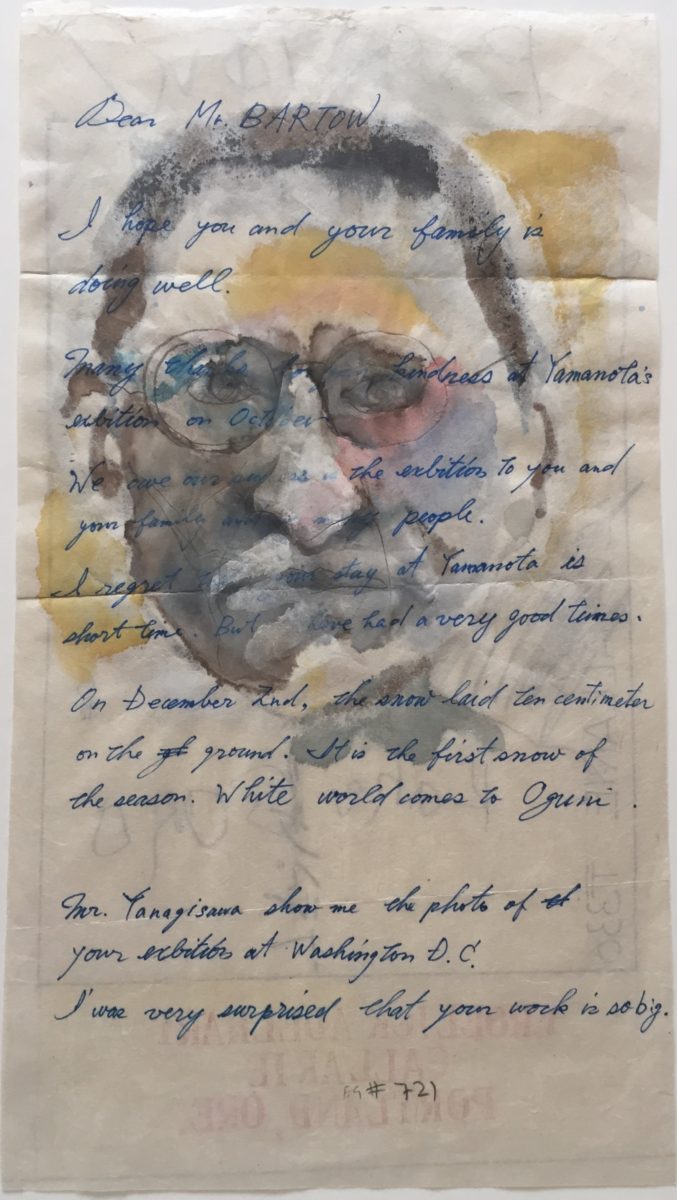

The note on the reverse side of the work reads as follows:

Dear Mr. BARTOW

I hope you and your family is [sic] doing well.

Many thanks for your kindness at Yamanota’s exhibition in October.

We owe ourselves is the exhibition [sic] to you and your family and (illegible) people.

I regret the your stay at Yamanota is [sic] short time. But (illegible) have had a very good times.

On December 2nd, the snow laid ten centimeter [sic] on the ground. It is the first snow of the season. White world comes to Oguni.

Mr. Yanagisawa show [sic] me the photo of your exhibition at Washington, D. C.

I’was [sic] very surprised that your work is so big.

Beneath the note is written #721. What that number means is anybody’s guess.

I had no idea who Goro Kakei might be so when I returned home I queried Charles Froelick about it. “Goro Kakei is a terrific artist, born 1930 in Shizuoka, Japan” he wrote. “He made many prints, sculptures, drawings. Bartow was able to meet him on one of his visits to Japan.” I also posted images of the work on Facebook, which Mr. Froelick reposted. Much to my surprise, it elicited the following response from Seii Hiroshima, a master printmaker who worked with Rick Bartow on many occasions: “What a surprise, Charles Froelick! I didn’t know Rick had drawn Goro’s portrait. I remember Rick was very much impressed by Goro’s works when I showed him them at my gallery in 1997. The letter behind Rick’s self-portrait must be from KIMURA-San from OGUNI town office.”

The mystery of who wrote the note on the reverse of Goro Kakei was now solved – sort of. If someone called Kimura-san was, in fact, the author of what is written on the back of the work, who was he? I once again contacted Charles Froelick. “Oguni town is [a] small village. . . . It’s in Niigata prefecture on the northern main island, near the Sea of Japan. . . .,” Froelick wrote back. “I think Kimura-san was someone who worked for the regional government who helped fund the Oguni community exhibit and meeting house that hosted Rick’s shows.”

Goro Kakei is a work that continues to fascinate me. When and under what circumstances was the note added to Goro Kakei? We may never know, but it is fun to ponder.

Rick Bartow often incorporated words into his work. It is an aspect of his art that I find extremely thought provoking. Grumpy is another such a work.

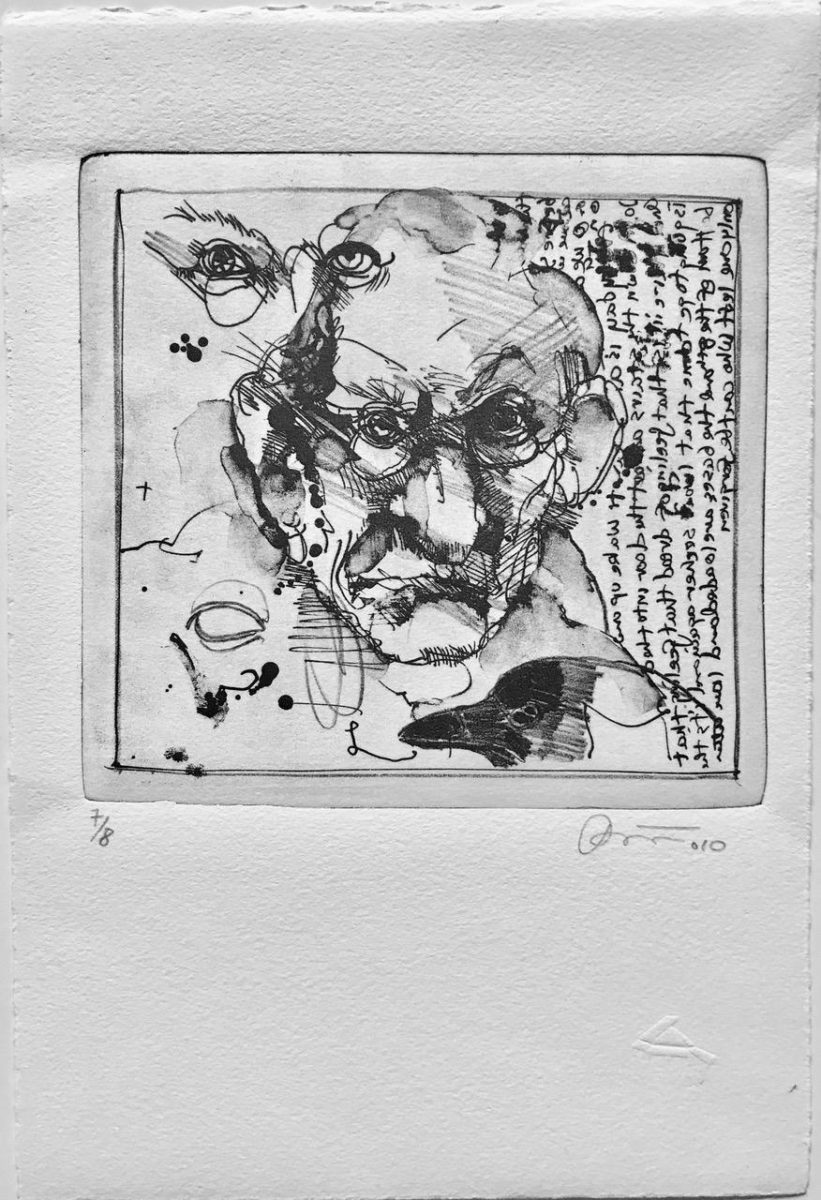

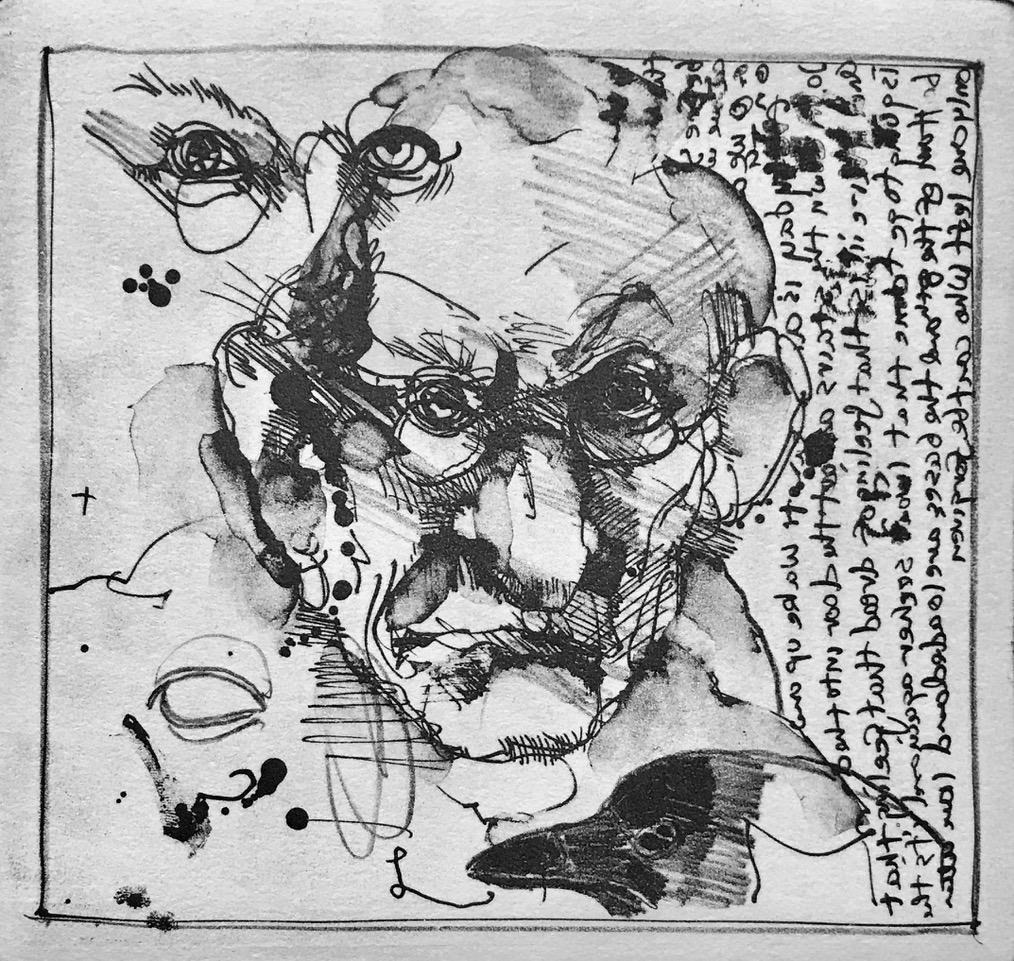

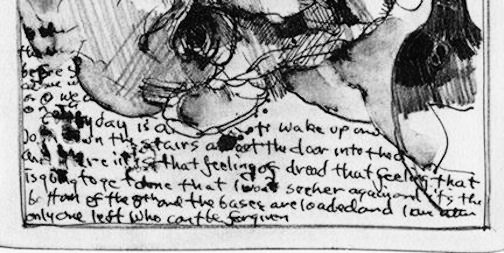

Grumpy by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, lithograph, ed. 7/8. 11.25” x 7.5” (2010). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Grumpy (detail).

Grumpy is one of the artist’s many self-portraits. The print contains a number of interesting and even cryptic elements. A bird’s head (possibly a crow or raven) appears at the bottom right of the print and when looked at closely (a magnifying glass helps) the crow, like Bartow, appears to be wearing spectacles. The artist often used animals as a sort of stand in for himself with various species representing different aspects of his personality. Both the crow and raven are regarded as mischievous tricksters and each has consistently appeared in Rick Bartow’s work.

On the bottom left of the page is another image that is even more enigmatic: an eye without a pupil, which might represent an inability to see. Eyes are another frequent symbol in Rick Bartow’s work and there are two pairs of bespectacled eyes in Grumpy. The artist’s eyes in his self-portrait look angry, while those in the partial face above it appear happy. These images may represent the artist’s moods.

Cropped and flipped image of Grumpy courtesy of Wilder Schmaltz and the Froelick Gallery.

Perhaps the most puzzling detail of Grumpy is that words are written vertically down the right side of the page. Reminiscent of Japanese prints, which had a strong influence on the artist, the writing seems to make no sense. At first I thought that what I was looking at was some sort of code. Then, it dawned on me that the words appear to have been written backwards so I held the print up to a magnifying mirror and I was able to decipher most of what the artist wrote. Some of it was obscured by ink splotches, which create a spontaneous feel. The writing begins illegibly and, then, continues as follows: “Everyday is a (illegible) Wake up and go down the stairs into the (illegible) it is that feeling of dread that feeling that is going to get done that two secher [sic] and it’s the bottom of the 8th and the bases are loaded and I am the only one left who can’t be forgiven.” This statement gives us a an insight into the artist’s emotional state at the time he created Grumpy. As I frequently do, I contacted Wilder Schmaltz, Assistant Director of the Froelick Gallery, about this aspect of the print. “This piece was executed during a residency at the Pilchuck Glass School, in 2010,” he wrote back, “the darker tone of this text,” he wrote back, “could be related to a couple of factors: That was a fairly volatile moment for Rick’s personal relationships. He didn’t particularly like working in glass. . . and what’s more, the banging, popping, roaring glass studio noise unfortunately set off his PTSD. To get away from all of that, he set himself up in the Pilchuck print shop and made a number of quite strong images, including this one.”

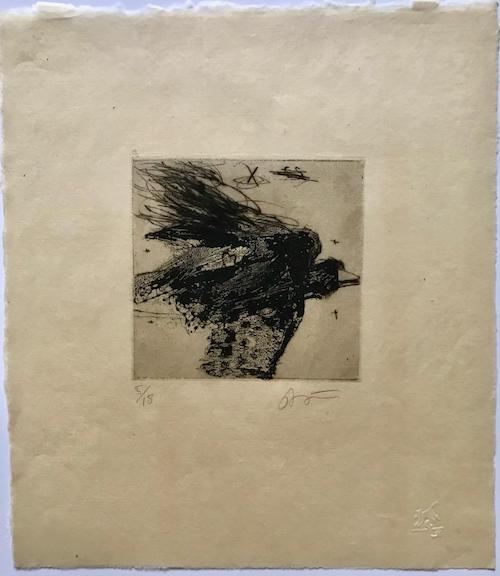

CH Crow by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, intaglio etching with some drypoint, ed. 5/18, 11” x 9.5” (2007). Collection of E. J. Guarino

CH Crow (detail).

CH Crow is another Bartow print that continues to intrigue me. It, too, contains a mystery though this one may never be solved. No one knows what the letters CH stand for in the title. I queried Wilder Schmaltz who commented as follows: ““I don’t have an idea of what CH might mean off the top of my head, perhaps a dedication to a friend, an artist? He’s being a bit obscure by using these initials. . . .”

Beyond this enigma, there is much to savor in CH Crow. The print typifies what Rick Bartow termed “mark making”. The work has an amazing textural quality as well as a sense of movement, which makes it seem as if the crow is flying across the page. In addition to the puzzling title, the work has a number of other unusual characteristics. The imprint on the bird’s lower wing as well as on part of its body resembles patterns on fabric. The upper wing, however, is made up of a series of lines as if they were scribbled on the page. This is something that the artist frequently did when drawing on the printing plate to impart a sense of spontaneity. The print also contains a number of strange marks: an X in the middle of two circles, the letters C and S scratched out, and four small crosses in various places on the page. What they signify remains unknown.

As with Yanagissawa Hawk 100, Salmon Boy, Goro Kakei, Grumpy, and CH Crow, I can return to any of the Rick Bartow works in my collection again and again and ponder some aspect I had previously overlooked. I consider them some of the most important pieces in my collection. They are mysterious, complex, intense, and visceral and reflect the concerns of an artist trying to sort out the complexities of life. Often filled with pain, rage and, sometimes, humor, Rick Bartow’s art cannot easily be confined to culturally based interpretations. It defies categorization. Over the years, Charles Froelick and Wilder Schmaltz have assisted me in acquiring works by Rick Bartow and they have also graciously given of their time to answer questions about individual works. I make no secret of the fact that I am a great admirer of Rick Bartow’s work and, in addition to acquiring his work, whenever possible, I advocate for it to be exhibited. It is the best way to keep the legacy of this major artist alive.