Collector's Corner

A VERY GOOD YEAR: Selected Works from the 1962 Annual Cape Dorset Print Collection

Every year collectors from around the world vie for the prints produced by the small Inuit hamlet of Cape Dorset. Since 1959 a print collection has been released every fall without interruption. During the earliest years of production, the prints produced by the Cape Dorset artists were considered “primitive” rather than contemporary art and each print sold for just a few dollars, a far cry from the prices Inuit prints command today. The prints were also often denigrated and trivialized by some as “airport art” because that is where they were most often exhibited and sold. The prints were also dismissed by some as “bingo art,” a snide reference to some Inuit who used a portion of their earnings from the artworks they created to play bingo.

Although it is generally accepted that Picasso and other artists of his generation borrowed heavily from African and Oceanic art, it is less well known that Andre Breton and other Surrealists owe a debt to Inuit art. The Surrealists were fascinated by the multiple perspectives, distortions, emotional intensity, and seeming spontaneity of Inuit art. When the first generation of modern Inuit artists were initially given paper they wondered what they should draw. They were simply told, “Whatever comes to mind,” or isumanivi. What the rest of the world refers to as art, Inuit have come to call isumanivi.

To a large extent, Inuit graphics have been overlooked by most major American museums and only a small number of discerning collectors and curators have had the foresight to champion Inuit graphics for what they are: contemporary art. Even when Inuit prints have been collected by American museums they have rarely, if ever, been exhibited and, when they are, they are regarded as more of an ethnographic curiosity than as contemporary art. Inuit graphics are usually presented as the product of a group rather than as the creative output of individual artists. Usually these exhibitions are grouped around such themes as Arctic animals, hunting, motherhood, shamanism, and camp life in the context of a romanticized version of how Inuit once lived a nomadic life on the land. However, from its beginning Inuit graphic art has been bold and unique. Inuit artists have always made and continue to make highly personal artistic statements. Working in a wide range of styles and genres, Inuit graphic artists have created works that reflect their world and their concerns. A number works produced by Inuit artists portray the world around them in a ways which give the impression that there is more than meets the eye in terms of what the viewer is seeing. This oddly disturbing quality is often referred to as the Inuit surreal. Although Cape Dorset community members were learning printmaking techniques for the first time in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the prints they created were highly artistic and extremely sophisticated, something that few realized at the time. One of the most exciting early annual print collections was produced in 1962.

From 1959 to 1961 the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection was made up of stone cut and stencil prints. In 1962 it was decided that the artists had progressed to the point where they could attempt two new printmaking techniques: copper engraving and line etching, which would allow the artists to draw directly onto the plate instead of the artist’s drawing being transferred and interpreted by a printer. The first Cape Dorset print artists were of varying ages, but predominantly older members of the community. A number of these artists, notably Kenojuak Ashevak, Kananginak Pootoogook, and Pitseolak Ashoona, became well-known internationally.

In 1962, all but six of the seventy prints produced were etchings all in editions of 50. Along with the prints produced by Cape Dorset artists, prints from the community of Povungnituk were also included in the catalogue for the the 1962 Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection.

Over the years, Dorset prints have generally be released in editions of 50 though a few have been in editions of 30 and rarely in editions of 100. In the early 1960s annual collections consisted of sixty to ninety prints. Today, the annual collection is usually thirty or so prints.

Untitled (Animals) by Parr, Inuit, Kinggait (Cape Dorset), etching/gravure, ed. 25/50, 12 1/2″ x 17 1/2″ (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

When I first started collecting Inuit works on paper I was shown prints by Parr and I must admit that I had no appreciation for what I was seeing. At the time, my collecting was limited by the outdated notion of “primitive art.” As I continued to acquire Inuit graphics I came to realize that what I was seeing were very sophisticated works that were often abstract and surreal. Untitled (Animals) by Parr presents creatures that the artist encountered as a hunter. I was (and still am) fascinated by Inuit perspective, which is unique and which was particularly pronounced during the 1960s and 1970s. No one told the artists, “You must do it this way,” or “You cannot do it that way.” So, the artists did exactly what they felt they should do. Whenever I look at these early works I always ask myself, “What is going on here?” With a bit of thought, it is not that difficult to understand what the artist has depicted.

In Untitled (Animals), all of the animals are recognizable, though they are stylized. In addition to two geese and a dog, Parr depicts three mammals he would have hunted. From top to bottom, there is a walrus, a seal, and a whale. The representation of the seal is particularly interesting since its face looks canine. At first, this may seem odd, however, seals, especially the pups, do have faces that resemble that of a dog. In essence, the theme of the print could easily be said to be, “These are the animals I hunt and I sometimes do so with my dog.”

Untitled (Hunters and Animals) by Saggiak, Inuit, Kinggait (Cape Dorset), etching, ed. 50, 12” x 19” (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto

Acquired in 1996, Untitled (Hunters and Animals) by Saggiak was one of the first Inuit prints to enter my collection. Like a number of works from the 1962 Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection, it portrays a hunting scene. At the time, it had not been that long since the artists creating these works had been nomadic hunters and many were still engaged in subsistence hunting. The scene that Saggiak depicts is complex: a hunter has wounded a seal with an arrow, two other men are creeping towards it and, in the meantime, the hunter has aimed his bow and arrow at what appears to be a fox to keep it away from the seal. At the same time, the hunters’ two dogs are clearly barking at the two bears in the scene. It is more likely that what is being portrayed is the hunters trying to prevent the bears from stealing their kill rather than the polar bears being hunted.

Untitled (Hunting Scene) by Timothy Ottochie, Inuit, Kinggait (Cape Dorset), 13/50, 13” x 19” (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Untitled (Hunting Scene) by Timothy Ottochie, Inuit, Kinggait (Cape Dorset), 13/50, 13” x 19” (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Untitled (Hunting Scene) by Timothy Ottochie was also acquired in 1996. The work is fascinating not only because of what is being depicted, but also how the artist has chosen to do so. In the lower portion of the print, two hunters are fishing and have been successful. The figure on the right has just caught a fish with a kakivak, or pronged fishing spear; however, the figure on the left must get his catch before it is snatched away be a canine, most likely an Arctic fox. In the upper right side of the print, two large dogs are fighting over a fish. Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the print is the hunter who looks directly out at the viewer. Behind him is what is most likely a goose. In his left hand he is holding a throwing stick, a boomerang-like weapon, and in his left an inflated seal bladder attached by cord to upright spear throwers. The throwing stick was used to hunt birds; the spear throwers had bone darts which were attached to a line that had an inflated bladder at the opposite end that acted as a buoy, keeping wounded sea mammals close to the service.

Untitled (Man with Animals) by Kiakshuk, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), engraving, ed. 44/50, 12” x 19” (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

As an artist, Kiaksuk’s intent is not simply documentation. His work has a sense of mystery, playfulness, and often ventures into the surreal. One of the most fascinating aspects of his art is that the viewer has an awareness that what is being portrayed reflects the artist’s experiences of a life lived in the Arctic landscape.

In Untitled (Man with Animals) a figure, perhaps Kiakshuk himself, boldly looks out at the viewer as a variety of animals seem to whirl around him – four seals, a whale, an Arctic fox, a small fish, a creature comprised of a goose and a mammal, and a walrus. The hunter, with a slight smile on his face, proudly holds one of his hunting tools above his head. To the right of this central figure, another figure (perhaps this same hunter or another man) has caught a seal and is holding a thin pole with a hook at one end; to the left of the central figure is a hooded figure (again, perhaps representing the hunter himself, or his wife, or another man). The hooded figure is holding an inflated seal bladder used in hunting seals. Whether or not all three figures represent one person or three distinct individuals is open to interpretation. However, it should be noted that in Inuit works on paper different periods of time may be represented in the same work. As with perspective, Inuit artists do not adhere to strict rules regarding the representation of time.

Untitled (Bird and Seal) by Lucy Qinnuayuak, Inuit, Kinggait (Cape Dorset), etching, ed. 44/50, 13″ x 19″ (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Untitled (Bird and Seal) by Lucy Qinnuayuak is clearly representational, but not realistic. The two animals represented, though not completely realistic, can be identified: a snow bunting and a seal pup. However, the creatures are not true to life since they are the same size. One of the aspects of Inuit graphics that has always fascinated me is that the rigid rules of perspective do not particularly interest Inuit artists. The artist’s intent is not merely documentation, but to show the importance of these animals. Seals provide food, clothing, tools, and fuel while snow buntings help keep the massive insect populations of summer in check. Each plays an important role in Inuit life.

Untitled by Pitseolak Ashoona, Inuit, Kinggait (Cape Dorset), engraving, ed. 37/50, 17 1/2 x 12” (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Arctic Artistry Gallery, Chappaqua, NY, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto

When I first saw Untitled by Pitseolak Ashoona in 2007 I had no idea what I was looking at. From my perspective, the work looked totally surreal. Try as I might, however, I couldn’t find anything even remotely recognizable to my eye in the image. It was only after Elaine Blechman, owner of the Arctic Artistry Gallery in Chappaqua, New York, explained to me what I was seeing did I have a better understanding of the print. As she often did, Pitseolak, as she is most commonly called, created a work with surrealistic elements that is rooted in reality.

The main focus of the print is a seal that is being kept afloat by inflated bladders employed by hunters for that purpose. One of the spear throwers used to launch the bladders can be seen in the upper righthand corner of the print. Completing the image are two bird heads that appear to emerge from the seal. One bird is eating an insect, which indicates that it is summer, the height of the insect season. It also suggests the importance of birds to control these hordes of pests that plague both humans and animals at that time of year.

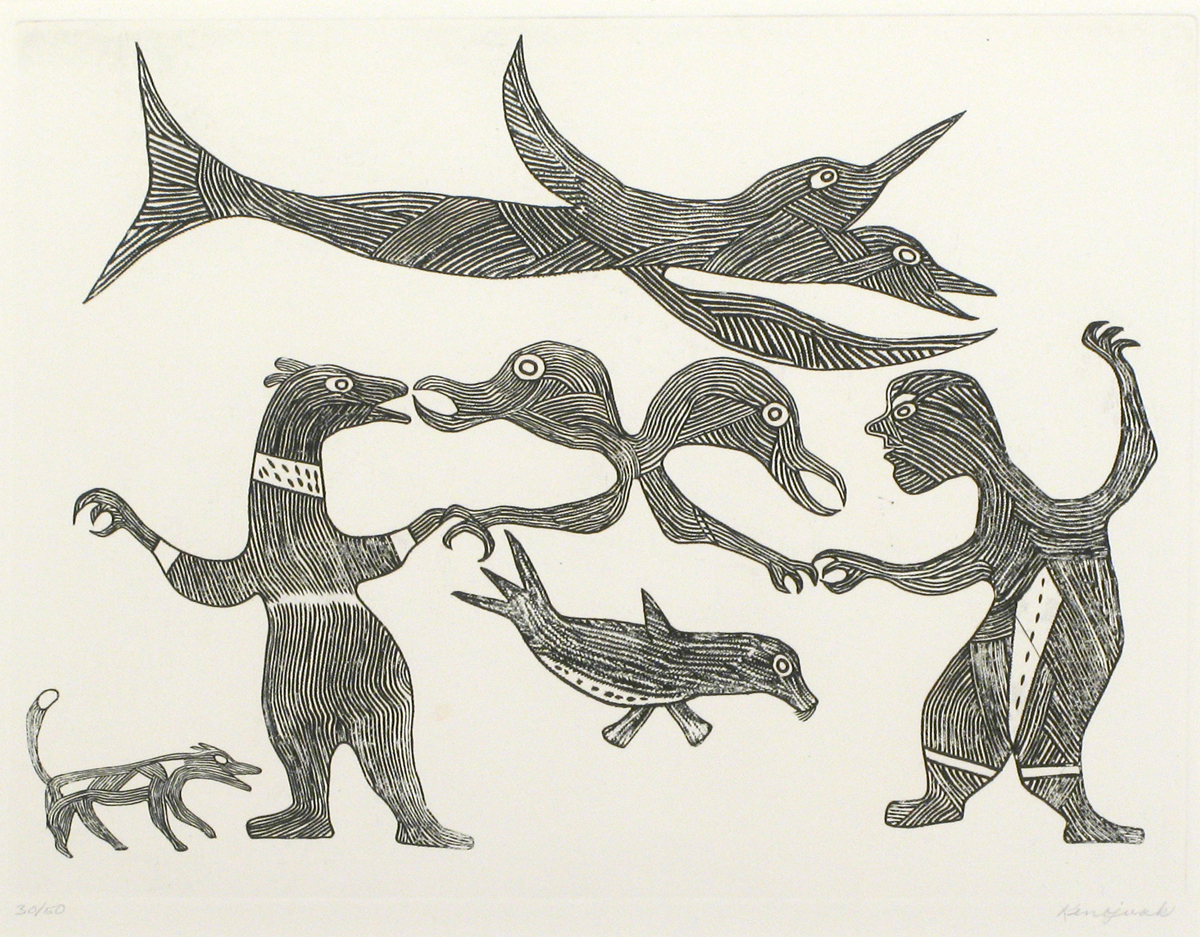

Untitled by Kenojuak Ashevak, engraving, Inuit, Kinggait (Cape Dorset) 30/50, 17” x 20” (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Kenojuak Ashevak is the most famous Inuit artist and is probably best known for her images of birds with fanciful plumage. However, her output was much more diverse. She also created works which focused on other Arctic animals and her drawings, which are little known, portrayed charming scenes of everyday life. Kenojuak also produced prints that were quite surreal, which illustrated creatures that may represent spirits or may be wholly imaginary. Clearly, Kenojuak took the concept of isumanivi. (“Whatever comes to mind”) seriously.

In an Untitled, another print from 1962, Kenojuak created a fantastical scene. A seal and a canine (either an Arctic fox or a dog) are easily recognizable as is a human figure on the right side of the print, but the rest of the scene is purely imaginary: a standing bear-like creature, conjoined bird heads with arms, and floating above is a creature that is an amalgamation of bird and fish. Clearly, Kenojuak has given free rein to her imagination in this print.

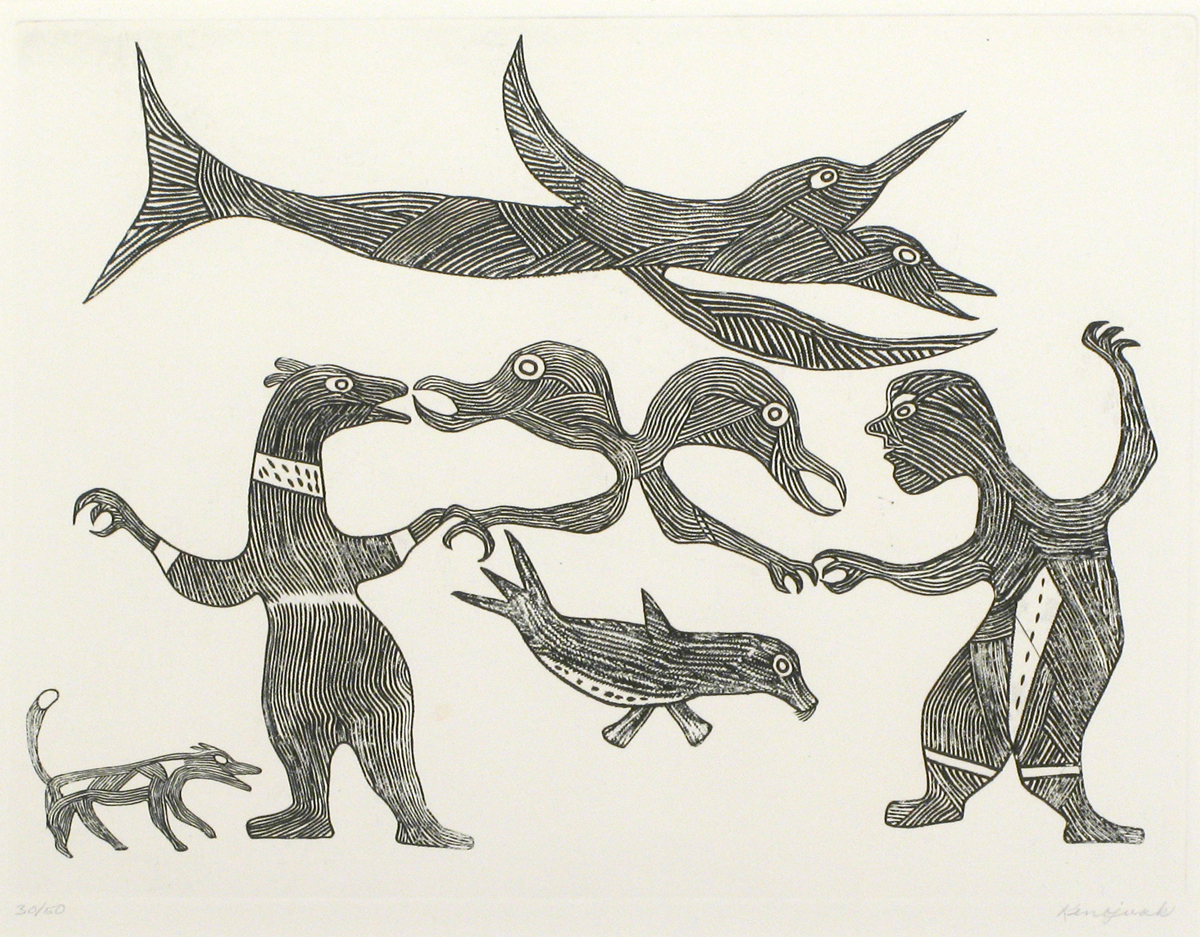

Untitled by Johnniebo Ashevak, engraving, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 34/50, 19¼” x 13¼” 1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Arctic Artistry Gallery, Chappaqua, NY, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Johnniebo Ashevak was the husband of Kenojuak Ashevak. Although they both started their artistic careers at the same time, Kenojuak became world-renowned while Johnniebo was overshadowed, so much so that in a number of cases his work was attributed to his more famous wife. Although it is not one hundred percent clear why this was done, putting Kenojuak’s name on a print may have been a marketing tool. As she became more and more celebrated, eventually becoming the most famous Inuit artist, a work with her name on it would be more likely to sell as opposed to one with her husband’s name.

Although often overlooked, Johnniebo’s work is quite wonderful. Untitled, an early print by him, typifies the Inuit Surreal. When the first generation of Inuit artists were told to put on paper whatever came into their head some created works that portrayed life as it was once lived on the land; others produced images of iconic Arctic wildlife, and a number of artists created works that had a strange, dreamlike quality. In Johnniebo Ashevak’s untitled print from the 1962 Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection, an unearthly creature resembling a merman is surrounded by nonrealistic renderings of Arctic animals, giving the piece a phantasmagorical quality. Three of the creatures are somewhat recognizable – a bird, a seal, a fox – but the fourth in the upper left portion of the print appears to be a combination of animals, a sort of bird with hands, perhaps meant to suggest transformation. Whatever the artist’s intent, he created a unique work. It is also interesting to see the similarities between Johnniebo’s work and that of Kenojuak, though we can only speculate on how they influenced one another.

Parr, Saggiak, Timothy Ottochie, Kiaksuk, Lucy Qinnuayuak, Pitseolak Ashoona, Kenojuak Ashevak, and Johnniebo Ashevak are just a few of the artists who contributed to the 1962 Cape Dorset Print Collection. These artists, who were part of the earliest Cape Dorset Annual Print Collections, have come to be known as the First Generation. Unlike other artists, Cape Dorset graphic artists work side by side at the Co-op rather than in isolation. The First Generation helped, inspired, and also influenced each other as well as younger artists. The work of the First Generation continues to inspire present day Inuit artists and is still sought after by collectors. No longer disparaged as “primitive,” the work of the First Generation of Cape Dorset graphic artists has come to be appreciated for what it is – contemporary art. This change in perspective can be credited in large part to the efforts of farsighted gallerists such as Pat Feheley (Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto), Robert Kardosh (Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver), Elaine Blechman (Arctic Artistry Gallery, Chappaqua, NY) and to Will Huffman (Dorset Fine Arts,Toronto). The early prints, as well as drawings, are now seen as sophisticated works by artists who expressed their experiences, thoughts, and feelings on paper for the first time in Inuit history.

To see the entire 1962 Annual Cape Dorset Print Collection click on the link below: