Collector's Corner

AND THE SHIP SAILS ON: More on Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s Trade Canoe Series

“They’re all trade canoes, something is being traded and in most of my political statements it’s about money being traded for quality of life.” Jaun e Quick-to-See Smith

In the summer of 2009 I visited the Indiana University Art Museum in Bloomington. When I reached the very end of Art of the Western World: Early Medieval to the Present I encountered Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s Sage and Sweetgrass. It was the first time I had ever seen the artist’s work.

Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, SAGE AND SWEETGRASS-1989-Oil on canvas -Copyright 2009, Indiana University Art Museum: Gift of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York; Hassam, Speicher, Betts and Symons Funds, 1993 (#93.6). Photographers: Michael Cavanagh and Kevin Montague.

The painting, completed in 1989, intentionally resembles a collage, the paint applied in broad strokes. A canoe, three pottery forms, a fish, and a cruciform shape similar to a Native woman’s tunic-style clothing are suggested by black outline. Of these images, the canoe seems to have been subconsciously imbedded in my mind.

Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith, Trade Canoe for Don Quixote, 2004. Mixed media on canvas, including acrylic, pencil, charcoal and oil; 60 x 200 in. Denver Art Museum: William Sr. and Dorothy Harmsen Collection, by exchange, 2005.62A-D. © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Photography courtesy of the Denver Art Museum.

It wasn’t until 2015 that I again saw more of the artist’s work – Trade Canoe for Don Quixote, a massive mixed media painting on four panels at the Denver Art Museum. This work is a powerful indictment of war, a cargo that has been transported around the world throughout history.

I was hooked and set about wanting to know in what other works the artist had used the metaphor of the trade canoe. Unlike the vessels that have always transported people and goods, and with them their concepts and beliefs, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s Trade Canoes are filled with symbols and, by extension, ideas. The concept of the trade canoes fascinated me and I wanted to learn more about them.

In August 2017 I had the privilege of meeting Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and in the fall we began an ongoing Email correspondence. We discussed many subjects, including the canoes. “I began painting a Trade Canoe in the beginning,” the artist explained, “knowing they brought small pox smeared blankets, wormy beef and moldy flour to clothe and feed my tribe. But as I thought about them, it became a metaphor for trading good things like land and culture for evil things like disease, homelessness, loss of land, loss of culture.” I also learned that the trade canoes had been created in a variety of media – mixed media paintings, drawings, prints, and sculpture – and were located in various institutions and galleries around the country. Others are still in the artist’s possession. Since I couldn’t travel to see them all, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith provided me with images and information about them.

The various Trade Canoes are a format that allows the artist to express her concerns on a wide range of subjects – historical, societal, spiritual, environmental, political – that concern her. They comprise an ongoing series.

Trade: Gifts for Trading Land with White People (1992) – Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People), 1992, oil paint and mixed media, collage, objects, canvas, 152.4 x 431.8 cm (Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia).

Trade: Gifts for Trading Land with White People is Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s response to the quincentennial of the arrival of Columbus in the Americas, which she considered a non-celebration. The immense work is comprised of two sections with the lower part consisting of three panels that form a triptych, which is a large mixed media painting. The canvas was painted in many layers, some consisting of strong brushstrokes and paint drips reminiscent of the work of the Abstract Expressionists. Although the artist used white, green, and yellow paints, the predominant color of the work is red, which is suggestive of blood, war, and anger. Collaged into the work are newspaper clippings and stereotypical images of Native Americans found on photographs, comics, advertisements, labels from fruit cartons and wrappers for tobacco and gum as well as images of deer, buffalo, and Native American men in traditional regalia as a counterpoint. Applied to these materials are patches of red, green, yellow and white paint. The final layer consists of a large, empty canoe that appears to be mired in the paint. Unlike its historical counterparts, this trade canoe is immovable. All of these elements would have been powerful on their own, but Smith added an additional wallop. Above the mixed media panels she hung a chain and suspended from it a variety of inexpensive objects that illustrate how Native Americans have been stereotyped in American culture. Smith is suggesting that these items be traded back for the land that was taken by colonists from Native tribes who received worthless trinkets in exchange.

Tongass Trade Canoe (1996) – Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Tongas Trade Canoe,1996, acrylic, mixed-media, and collage on canvas, 60” x 150,” Yellowstone Art Museum, Gift of John W. And Carol L.H. Green. Photo courtesy of the artist.

In Tongass Trade Canoe Jaune Quick-to-See Smith expresses her concerns for environmental issues confronting us. Tongass National Forest is the largest forest in the United States. Located in Southeast Alaska, it covers 17 million acres and is the only natural rainforest remaining in the state. The Tongass is rich in plant and animal life and is a calving ground for caribou that migrate there. This is suggested by the images of caribou that float across the painting. Collaged into the work are newspaper clippings that reflect the many different positions with regard to rainforests such as a chart of oil reserve rights, the children’s rhyme “Rain, Rain, Go Away,” as well as advertising slogans. Above the main section of Tongass Trade Canoe is a wooden shelf (a product of the forest) with eight colored plastic baskets (a by-product of oil). Forests around the world are under threat from both the logging and oil industries. The canoe of the title, rendered in outline form, is empty and has a ghost-like quality. It causes the viewer to wonder what exactly we are getting in trade for our natural resources.

Untitled (Trade Canoe) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, oil and acrylic on canvas, 24 feet long and 12 feel high. three panels (1999). Ridgedale Branch of the Hennepin Library, Minnetonka, Minnesota.

The painting that Jaune Quick-to-See Smith created for the Ridgedale Library reflects her love of books. This large work is about Minnesota – the land, the people, the history, and literature. “It has history” the artist stated, “like Charles Lindburgh came from Minnesota, writers like Louise Erdrich live there, I think Meridel LeSueur lived there too, she wrote A Peoples History of Minnesota.” Jaune Quick-to-See Smith also included quotes from books by the authors that are in the library’s collection. The artist acknowledged the many nationalities that contributed to Minnesota by including their languages in the work. Native Americans are honored by the use of imagery: people, animals, trees, water, transportation, and the landscape. “I researched the Chippewa canoes to paint the birchbark canoe on the painting. I wanted to make sure Indian people were accounted for in the history of Minnesota. The canoe was their important mode of travel in the land of 1,000 lakes,” Smith explained. “I put birds (the Loon) and animals, I was thinking of children,” she added, “thinking of what’s in the library… I had some funny stuff too like in the upper right hand corner is a big mosquito–I read somewhere (in my extensive research) that ‘It is said the state bird of Minnesota is the mosquito.’”

Trade Canoe: Don Quixote in Sumeria by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, oil and acrylic on canvas, 60” x 200” four panels 2005). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Created during the same era as Trade Canoe for Don Quixote, Trade Canoe: Don Quixote in Sumeria employs many of the same symbols: images from Picasso’s Guernica, a skeleton wearing a hat and riding a skeleton horse, skeleton’s throwing themselves out of the canoe, a cross, a pitchfork, a devil’s head, and Mickey Mouse’s gloved hand. This painting is also an indictment of war, in this case the War in Iraq. “Of course I was masking Bush’s name,” Smith stated, “by calling him Don Quixote and calling Iraq Sumeria.” In a further Email correspondence, the artist went on to say, “ It was an easy move . . . to the war in Iraq, especially when they were robbing the museums, setting up Pepsi factories etc. Things were bad under the dictator but I wonder about the plight of the people now.” Smith was fascinated with the idea of the Trade Canoe beached out in the sands of the desert laden with images from war, pictures going back in history as well as pop symbols that represent America.

Maquette for Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, charcoal, pencil, collage, conte, and pastel, 30” x 40” (2015). Private Collection. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, acrylic, collage and mixed media on canvas, 3 panels 40” x 60” (2015). Private Collection.

Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, acrylic, collage and mixed media on canvas, 3 panels 40” x 60” (2015). Private Collection.

Often Jaune Quick-to-See Smith creates a maquette that is used for the basis of a large-scale painting. She did this with Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights, which the artist stated “. . . is a Salish version of Noah’s ark.—with Coyote as the centerpiece because s/he is part of our creation story. Coyote helped Amotken turn on the lights (the sun) and Coyote is in charge of the welfare of the Peoples. . . . I used the Biblical story about Noah and the flood, inserted Coyote as the central figure and animals, plants and images from art history to replace the Biblical images in the story. . . . instead of the animals that Noah chose–all from the Middle East, I chose plants, fish, animals (from my reservation) and contemporary images such as Keith Haring, etc.”

Canoe by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, photoshop (2015). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Canoe by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, photoshop (2015). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith also used Canoe, a work that only exists on the computer or on paper, as a maquette for Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights. “This is completely photoshop,” Smith explained. “I gathered all the images and then asked Neal [the artist’s son] if he could manipulate them for me. . . . By the time I did an actual painting using this as my maquette, it turned into the Forty Days and Forty Nights. . . .Then this same computer maquette wasn’t done yet–it became the template for the Metropolitan commission which I revised again for the lithograph [Trade Canoe: A Western Fantasy].”

Trade Canoe: False Gods by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, charcoal, pencil, pastel, conte, 30” x 40” (2015). Private Collection. Photo courtesy of the artist.

As in other works by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Coyote, the Trickster, is the central figure in Trade Canoe: False Gods. Other imagery includes masks, skulls, a small bear, what looks like a peacock feather with an “eye”, a spider and it’s web, a totem pole, four figures that look very much like the stereotypical image of Tonto from the Lone Ranger TV series and a bird swooping down towards the canoe. Below the canoe is a fish, a staple of the Northwest Native diet, but also a symbol of Christ. On the left of the drawing, a hand reaches into the scene, rays pouring out from it.

I was curious about these images with which the artist chose to load her canoe and queried her about them.. “The figures in the canoe are masks or totems that white people would burn seeing them as dangerous or false gods,” she explained. “Yet the truth is they were images used in ceremonies to celebrate life often related to specific families thus keeping family history alive and infusing the tribe with re-acknowledgement of it’s cultural ways.” The small bear is a reference to George Caleb Bingham’s 1845 painting Fur Traders Descending the Missouri, which contains the image of a baby bear, though it looks more like a cat. The artist agreed that the four Indians are a reference to the 1950’s TV character Tonto, which reinforced the idea that Native Americans “talked baby talk and weren’t too bright.” Jaune Quick-to See Smith draws from art history as well as pop culture. She stated, “The bird in the upper righthand corner of the drawing was inspired by those found in the work of Wilfredo Lam, a Black and Chinese artist, whose works were seen as ‘primitive,’ but are now regarded as ‘high art.’” She went on to say that the spider and web are about the stories woven throughout history, including modern news reports that are slanted to favor one point of view. As for Coyote, Smith said that s/he, “. . . is loosely drawn from a possibly 5,000 year old Salish bone carving. The length of time he has been serving Salish peoples as teacher and Trickster is quite amazing. He is not a god we are worshipping, he is part of our creation story, just like Genesis is in the Bible.” Finally, what looks like a peacock feather was inspired by Surrealism. The artist said that it represents an “eye” that is watching all and “references memories, feelings and dreams with illogical images . . . .”

Since the artist once again uses the metaphor of trade in Trade Canoe: False Gods, it makes one contemplate what Native Americans received in return for giving up their traditional spiritual beliefs. In most cases, it was subjugation, disease, and violence – not exactly a fair trade. According to the Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “In stories about Europeans ‘discovering’ us, they always write about our ‘Gods’ which is a fallacy. Our tribes believe in a Life Force that flows through everything even rocks and mountains. And they refer to the spiritual world. But of course if its not Christianity, it doesn’t count for anything and it’s sinful.”

Trade Canoe: Adrift by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT acrylic on canvas, 2 panels 40” x 60” each (2015). National Museum of the American Indian Collection.

The immediate impression the viewer gets from Trade Canoe: Adrift is a sense of chaos. Multiple bright yellow, whirling suns hang over the scene and the water beneath the canoe seems streaked with blood. Masses of people are crowded together in the vessel and the expressions on the large figures seem angry and frightened. We are presented with a world out of balance and in turmoil. The viewer is asked to consider what we have traded for the world in which we now live. The aptly chosen title suggests that, as a species, we are drifting aimlessly, ignoring the consequences of doing so.

Before creating Trade Canoe: Adrift, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith had been visiting her friend who is the Duwamish Tribal Chair. They discussed the thirty year struggle to receive Federal recognition for her tribe without which they cannot fish for salmon, one of the mainstays of their culture. At the same time, immigrants from Syria and throughout the Middle East were losing their lives crossing the Mediterranean in an attempt to reach Europe. “I was documenting both plights in this one painting,” Smith stated. “So yes, that’s why its so crowded. That’s also why there’s intense sun. I combined all the tribal peoples suffering at the hands of oppressive governments.”

Maquette for the lithograph Trade Canoe: A Western Fantasy by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT charcoal, pencil, collage, conte, 30” x 40” (2015). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Trade Canoe: A Western Fantasy by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, lithograph, 18/40; printed by Landfall Press, Santa Fe, NM; published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in conjunction with the exhibition The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, 21” x 30” (2015.).

Trade Canoe: A Western Fantasy is filled with references to the paintings of George Caleb Bingham, Frederic Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt as well as posters for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, Hollywood movies, literature, Davy Crockett Almanacs, comic books, and especially Tonto and the Lone Ranger. The artist stated, “I added some images and issues that concern me such as oil barrels (before Standing Rock) and a cactus bed to signify climate change with an elk and bison to represent endangered wild life.”

Central to Trade Canoe: A Western Fantasy is an image of a coyote, a trickster who plays an important role in Smith’s work. In an Email correspondence, Smith went on to explain more aspects of Trade Canoe: A

Western Fantasy: “In my lithograph, the clusters of lines become a frame for my curious Western fantasy, which of course never happened, but then neither did most written histories nor the historical painted images either. I even added an alien, since our congress makes laws about ‘aliens’ that are really Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This proves they don’t know their history either. So perhaps my version might have more truth.

Trade Canoe: Starry Starry Night by June Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, charcoal, 30” x 40” (2016). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Anyone familiar with art history immediately gets the reference to Vincent Van Gogh’s painting The Starry Night in Jaune Quick-To-See’s Trade Canoe: Starry Starry Night and, for people of a certain age, the title also alludes to “Vincent (Starry, Starry Night)” a 1971 song by Don McLean. The artist said that she used Van Gogh’s title to convey the idea of traversing the unknown. She also stated she had read Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki and Aku-Aku and other books about “the mariners in the Pacific who navigated by the stars and an object of woven sticks (a star chart I think it’s called.) The Indigenous peoples also used the salinity of the water to guide them. This canoe, filled with samples of Native humanity and teaching stories, is like a Noah’s ark too.”

Trade Canoe: The Garden by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, charcoal, 30” x 40” (2016). Photo courtesy of the artist.

As with all of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s work, Trade Canoe: The Garden is filled with striking imagery. Crowded into the vessel are a giant rabbit, skulls and Coyote pointing the way as he says something indecipherable. The canoe moves through waves that resemble wings, while behind it a salmon leaps from the water. Behind the canoe is the outline of a cactus plant. In the sky above another rabbit stands on a crescent moon on a whirlwind, while a Divine hand points downward. A brown, smiling face looks on while a green star, resembling depictions of the Star of Bethlehem shoots across the scene. Nearby is an American eagle and a winged figure.

In an Email correspondence the artist spoke in detail about the drawing. “The Garden,” she stated, “(as in Adam and Eve) but like Noah’s Ark, they are carrying plants in order to survive somewhere else–the trade is that with Glyphosate and other poisons and pesticides our native plants are dying. Also waterways that have been altered are causing Indian peoples to lose their foods (like salmon) and livelihoods–like Salt River Pima’s willows for their basket making and the Juncus Reed in California, same thing– have disappeared due to development. My Salish tribe had an indigenous trout in Flathead lake but we have an invasion of an alien fish (from Asia) that is killing our trout.”

Rabbit petroglyph Peterborough Site, the Canadian Shield. Photo courtesy of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.

I was particularly curious about the giant rabbit that dominates Trade Canoe: The Garden and queried the artist regarding it. It is a figure that appears often in the artist’s work. “The rabbit,” Smith explained, “is the Giant Rabbit, Nanabozho, part of the creation story for the Ojibwe, Chippewa, Cree: He is a trickster. In the Southern U.S., rabbit is a trickster too. Br’er Rabbit is patterned after the Native rabbit but African Americans say they brought Br’er Rabbit from Africa. It may be both. Anyway in Hollywood, Coyote became Wily Coyote, Rabbit either became Br’er Rabbit or “What’s up Doc?” the waskilly wabbit, the all knowing, carefree, Bugs likely based on Trickster Rabbit, Nanabozho, Giant Rabbit, Br’er Rabbit.” The artist went on to state, “There are standing rabbits pecked into petroglyphs at the Peterborough Site in Canada on the Canadian Shield that have been there since before the last ice age. . . . I have Cree ancestry from Canada, so I’ve used the rabbit sometimes with the Coyote that is part of the Salish creation story. Their jobs are to take care of the people.”

Trade Canoe for the North Pole by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, acrylic, collage, and oil crayon on canvas, 60“ x 160“ three panels (2017). Missoula Art Museum Collection.

Environmental issues are a driving force behind Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s work. In Trade Canoe for the North Pole she addresses her concerns about what is happening to the planet. “With climate change comes flooding, melting glaciers and changes in vegetation,” the artist stated. “Here a canoe is loaded with plants and animals that might be suited to the warming climate in the Arctic. It could be that palm trees and tropical life will find a comfortable zone there. Coyote is enjoying the sun and the moon drifting along like the tumbling tumbleweed. Trade Canoe for the North Pole has palm trees and cactus to plant, It’s also carrying an iceberg or a glacier much needed there.”

Maquette for A Trade Canoe for the North Pole by June Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, drawing/collage, charcoal, pencil, ink, 30” x 13” (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist.

A Trade Canoe for the North Pole (green state) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, lithograph ,15” x 22” (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist.

A Trade Canoe for the North Pole (red state) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, 3 color run lithograph, 15” x 22” (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist. Collection of E. J. Guarino

The same year she created the mixed media painting Trade Canoe for the North Pole, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith returned to the theme of climate change, producing a maquette for a lithograph titled A Trade Canoe for the North Pole as well as two versions of the print: a green state as well as a red state with a large red sun looming over the image. This canoe is also loaded with plant and animal life associated with southern climes, but which might one day survive in the Far North – palm trees, a serpent, a frog and a buffalo. As is often the case in Smith’s work, Coyote is a dominating presence.

Detail: A Trade Canoe for the North Pole (red state) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, 3 color run lithograph, 15” x 22” (2017).

On the right side of the Maquette for A Trade Canoe for the North Pole as well as the two prints based on it there is the image of a woman. To my eye, this figure looked very much like Jaune Quick-to-See Smith so I queried the artist about this possibility and she stated the following: “I think you’re right, I hadn’t thought about it, but I think it’s a common thing for an artist to draw or paint themselves into their work. I’ve seen that often, an artist does a portrait of someone else and it winds up looking just like the artist. I think we do it without realizing it. So sure, I’ll accept your observation

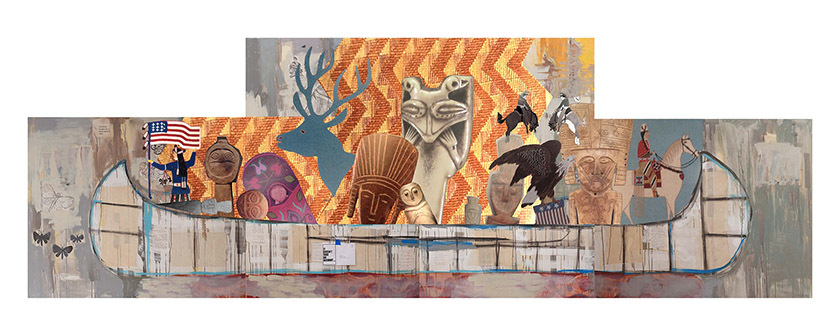

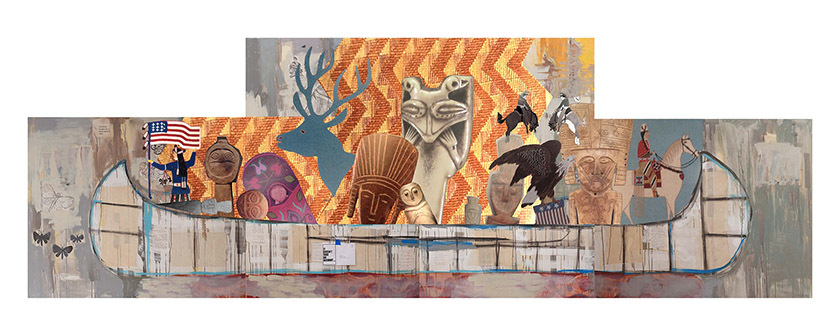

Ghost Trade Canoe by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, oil and acrylic on canvas with collage, pencil, pastel, oil crayon, 217″ long, 72″ high, four panels, the two end panels are 50”x 60″ and the two mid panels are 48”w x 72″h each. (2017/18). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Following in a long line of artists, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s mixed media painting Ghost Trade Canoe was inspired by the legend of the Flying Dutchman, a ghostly ship that appears and reappears on the sea, but is doomed never to make port. This tale, which may have originated sometime in the 1600’s, has been the inspiration for works as desperate as Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1797 – 1798 poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Washington Irving’s 1855 story “The Flying Dutchman on Tappan Sea,” Richard Wagner’s 1843 opera The Flying Dutchman, the 1951 film Pandora and the Flying Dutchman and TV shows such as Fantasy Island. In particular, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith cites Albert Pinkham Ryder’s 1887 painting Flying Dutchman as the inspiration for Ghost Trade Canoe. The artist considers the story that she is telling in her painting to be a particularly American one. “. . . like the Flying Dutchman, with reported sightings, this story keeps reemerging and then disappearing as it is kicked under the carpet. There are disappearing buffalo, peoples, Indians in the media (Tonto) and the traditional coyote Trickster is replaced with the modern white people’s Trickster, Wile E. Coyote. There’s also the disappearing bees and butterflies (to reference the changing environment).”

Trade Canoe: We’re All in the Same Canoe by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, charcoal, ink, collage, pencil acrylic, 20”x15” (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Trade Canoe: We’re All in the Same Canoe is a drawing/collage that became the basis for We’re All in the Same Canoe, a print that was done in a run of twenty. To produce the edition a photo litho plate was made from the drawing, then the artist added hand coloring and wrote “swear words” (*#+XX###&&??) in the bubbles. According to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “The title refers to the fact that we all breathe air, need water, need to be able to grow food, etc. The numbers in the right hand corner are part of a Bingo paper. I was able to get a few used ones from a casino, which I’m not supposed to have. I copy them and use them in my art especially when I want to show that something is a gamble.” Shortly after the print was produced the artist stated, “Climate change affects everyone, so do floods, a hole in the sky, political unrest and government oppression. But we all suffer together no matter whether we are red or blue.”

Trade Canoe: The Dark Side by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT acrylic, collage and charcoal, 160″ long x 40 inches high in three panels that are each 40” x 60” (2017/18

With it’s giant heads, George Armstrong Custer’s on the left and a Native American’s on the right, Trade Canoe: The Dark Side suggests the influence of the work of Robert Crumb and Phillip Guston, two artists who are sources of inspiration for Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. The left side of the painting is painted in dark colors while the right has a much lighter palette. Above the canoe is an eclipse from which a dark beam projects down to Custer from the blackness. As the sun emerges it shines a rainbow onto the Native figure. The work is clearly a reference to the Battle of Little Big Horn and the legacy of Custer who, until the 1960’s, was considered a hero in popular lore mostly through the efforts of his widow who, almost immediately, set about casting her husband as a soldier who had died valiantly fighting savage warriors. The Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes had a very different view of the battle and of Custer. The three books Elizabeth Bacon Custer wrote on the subject were extremely popular and influential. The image she promoted of her husband was popularized by “Buffalo Bill” Cody and Pawnee Bill in their Wild West shows. In 1912 the story first became the subject for film, but it wasn’t until the late 1950’s that the Native American perspective of the battle began to be presented in the medium. Custer is also responsible for the Washita Massacre, a surprise attack on a Cheyenne village in which women and children were used by Custer’s men as human shields and then killed. This was the era of Manifest Destiny and the U.S. Government was not going to allow Native Americans, whom it considered an impediment to the development of the railroads and of the settlement of the west, to stand in the way of what it considered progress. One tactic was to destroy the Indian’s food, shelter, and means of travel. The choice was surrender or die of starvation. The Government was determined to gain control of the western lands, even if it meant the extermination of the Indian.

The artist explained that Trade Canoe: The Dark Side was inspired by the eclipse in the summer of 2017. “I had been thinking,” she stated, “that something needed to connect these two guys but not like two friends. I did have a rainbow drawn across there, which just didn’t fit. But the eclipse fit perfectly with light rays shining on Tonto and the opposite side with Custer is the dark side of the eclipse. The canoe looks to be filled with decorative elements but when you look a little closer you see the elements are bones and picto-skeletons. There are lots of petroglyphs and pictographs in the Plateau area that show figures with bones sometimes called X-Ray Figures.”

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith went on to explain: “‘The Dark Side’ has two meanings–one is about the eclipse but the other is about the glorification of Custer in American history and very little truth about him and the U.S. military, the Cavalry and the government. This is the dark side of our history as its stands today. I use Custer as a symbol of all that.”

Trade Canoe with Bison by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, acrylic, collage and charcoal, plus flashlight and chain, 160″ long x 40 inches high in three panels: the two end panels are 50” x 60,” the middle panel is 40” x 60” (2018).

Before their mass extinction in the 1800’s, the bison population in North America numbered in the tens of millions, but by the end of the century less than 100 remained in the wild. The bison were were killed by white hunters for their skins and tongues while the rest of the animal was left behind to rot. Later, the bones were collected and shipped to the East where they were ground up to be used as fertilizer. In addition, the railroads advertised excursions for “hunting by rail.” Hundreds of bison were shot from moving trains as sport, leaving the bodies of the animals where they fell. Native Americans, on the other hand, used every part of a bison they killed. Trade Canoe with Bison presents a canoe laden with bison skulls under a fluorocarbon sky. (One title for the work originally under consideration was Trade Canoe: Fluorocarbon Sunset). Jaune Quick-to-See Smith said that she got the idea for Trade Canoe with Bison from an old photograph of a man standing in front of a mountain of bison skulls. “When the government was trying to get rid of us,” the artist stated, “one way was to get rid of all the buffalo and hope we starved to death and if that didn’t work then another reason was to keep us from hunting, which was an important part of our culture, in other words to keep us confined at the fort or to keep us imprisoned so they could control us.”

In Trade Canoe with Bison Jaune Quick-to-See Smith presents the viewer with bison skulls as literal mountains. Dominating the painting is a fluorocarbon sky: of blazing reds, pinks, oranges, and yellows. “The flashlight hanging on the painting,” the artist explained, “is a symbol to shine a light on this piece of our history. But the flashlight also was used by Jasper Johns not with the same meaning, I reference art history by using a symbol from art history. The fluorocarbon sky also needs a light shone on it, that’s a threat to our ozone layer.”

Frybread Canoe by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish, Kootenai Nation, MT, and Neal Ambrose-Smith Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, Metis-Cree, sculpture, wood, frybread, artificial waxed sinew, 141″ (11 feet) 20″ wide, 15″ high (2018). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Frybread Canoe is an exquisitely built sculpture that contains actual frybread. The piece is a collaboration between Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Neal-Ambrose-Smith, the artist’s son who is also an artist. According to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, this piece fits with Ghost Trade Canoe, Trade Canoe: The Dark Side, and Trade Canoe with Bison, three of the artist’s most recent works. “The Trade Canoes brought moldy flour upriver to our tribe,” Smith stated, “and we made fry bread out of it. Now it contributes to diabetes and heart disease. . . . I figure with this trade canoe I am returning the favor.”

I was curious about a technical aspect of Frybread Canoe: Doesn’t the frybread get moldy over time and, if so, how is that addressed? When I Emailed Jaune Quick-to-See Smith about this she replied, “. . . the grease hardens up and the frybread becomes like shoe leather. It petrifies.

Trade Canoe: Making Medicine by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish, Kootenai Nation, MT, and Neal Ambrose-Smith Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, Metis-Cree, sculpture, pine, sinew, water bottles, styrofoam trays, fast food coffee cups with plastic lids, wood crosses, hypodermic needles and red ochre paint, 12 feet long and 2-1/2 feet wide (2018). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Before it reached its final state Trade Canoe: Making Medicine had a few earlier incarnations and titles as Jaune Quick-to-See Smith worked out what she wanted this piece to express. The artist once again collaborated with her son, Neal Ambrose-Smith, who constructed the canoe by splicing wood, soaking it to bend it, and tying it with sinew and glue. The original plan for the sculpture was for it to contain figures made of muslin and linen thread and stuffed with recycled plastic bags. In the course of creating the piece, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith decided against this approach, removed the figures and, instead, thought she would fill the canoe with sweet sage, which “. . . will smell in the gallery . . . .” the artist stated. Eventually the artist decided against this approach as well, loading the canoe instead with water bottles, styrofoam trays, fast food coffee cups with plastic lids, wood crosses, hypodermic needles and painting it ochre red.

According to the Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, the idea for this piece came from learning about the now extinct Beothuk Tribe of Newfoundland who used to paint themselves their canoes, their household goods, their conical houses and their musical instruments with red ochre in the springtime. When the artist and her son attended Medicine Lodge ceremonies with their family in the summertime at Badger Creek, “the medicine people would paint our faces and hands with red ochre and we would also have red ochre on our blankets, clothes and personal items. Knowing that these ceremonies are about the renewal of life, we felt that using the Trade Canoe to trade plastic bottles, Hefty styrofoam, drug paraphernalia and Starbucks coffee cups for clean water and a clean environment would be making good medicine.”

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s interests are wide ranging and inform her work: art, music, literature, history, politics, and pop culture to name a few. In addition to the Indigenous art of the Americas, other influences are the work of George Caleb Bingham, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, Emanuel Leutze, Phillip Guston, Picasso, Kandinsky, Klee, Miró, Dubuffet, as well as art movements such as Surrealism, Cubism and Constructivism. Smith’s art is highly symbolic and contains stylistic elements of both abstraction and representation. She detailed her artistic process saying, “I work on multiple paintings at one time. Then, by going back and forth to each one, not in any order, and only when I can see what needs to be added, do I make any progress. This is what takes so long. . . . Sometimes a painting will sit for years. The oversized Ghost Trade Canoe, sat from 2010 to 2018. I kept it sitting in the studio, then I would take it down for awhile, then put it back so I could see it. . . . . I would work on it a bit but it just didn’t seem to be willing to come into this world and when it did, it came roaring, even the color changed.”

Although she has created paintings, mixed-media works, drawings, prints, and sculptures that explore a broad range of themes, there is nothing in the canon of American art history quite like the artist’s Trade Canoe Series. These unique works allow Jaune Quick-to-See Smith to fill her vessels with symbols that transport important ideas to the viewer. The trade canoes are clearly an important metaphor for the artist, who continues to create them, as well as for the audience she is addressing.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith for generously providing such a wealth of information about her art.