-

×

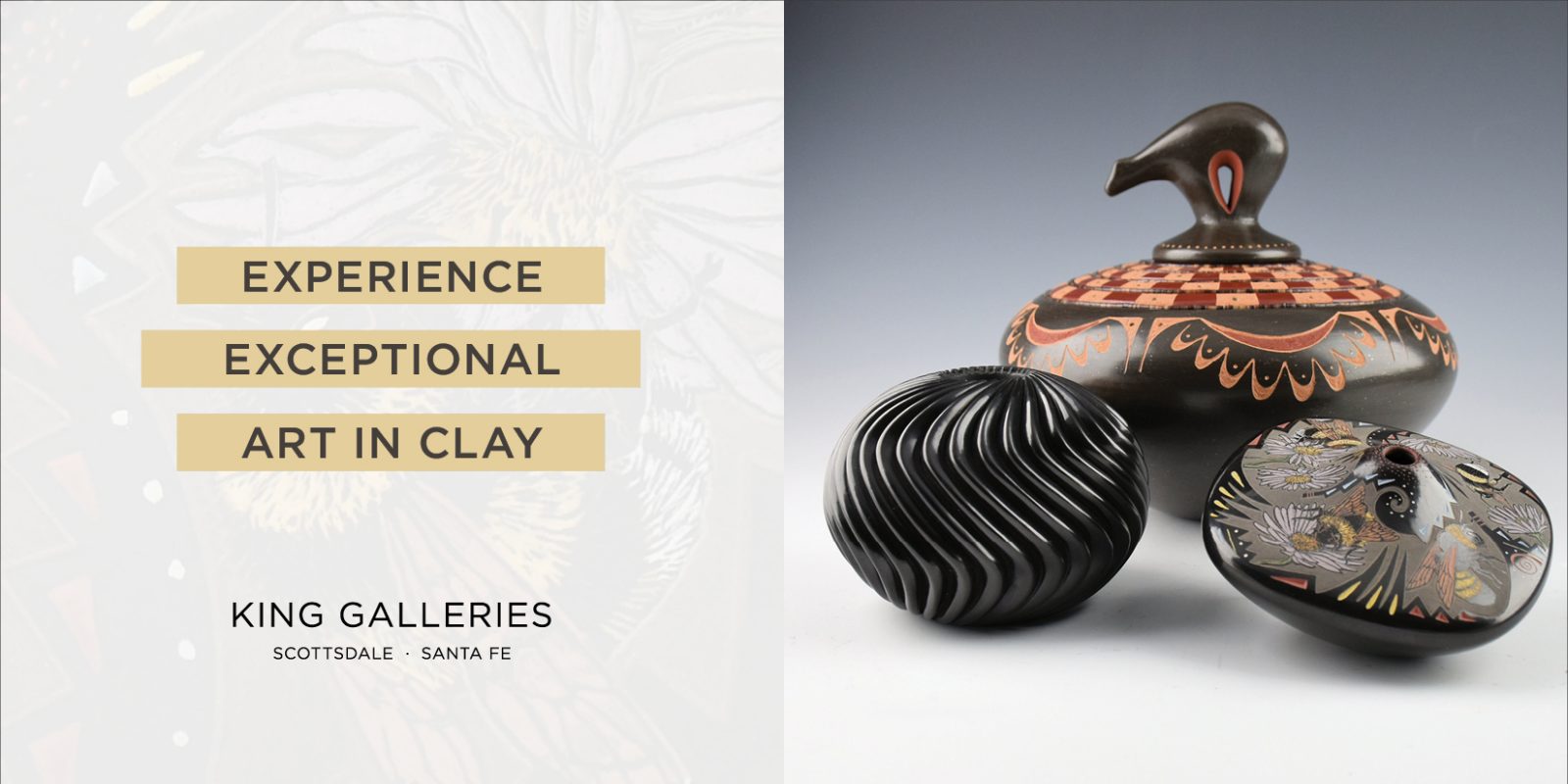

Borts-Medlock, Autumn - Golden Skies "Chaco Parrot", 12/35

1 × $ 9,600.00 -

×

Cain, Billy - Bowl with Carved Avanyu (1980s)

1 × $ 200.00

Cain, Billy - Bowl with Carved Avanyu (1980s)

1 × $ 200.00 -

×

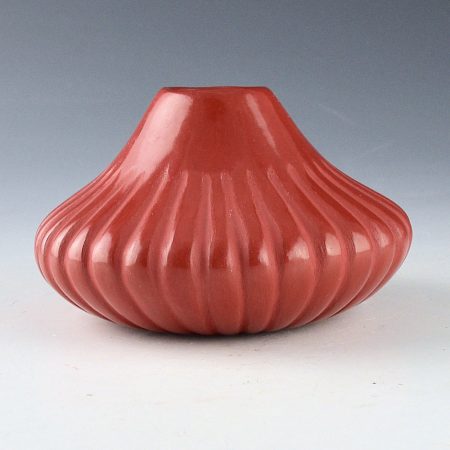

Baca David - Red 32 Rib Melon Jar

1 × $ 425.00

Baca David - Red 32 Rib Melon Jar

1 × $ 425.00 -

×

Madalena, Reyes - Jar with Lightning Designs

1 × $ 150.00

Madalena, Reyes - Jar with Lightning Designs

1 × $ 150.00 -

×

Vigil, Minnie - Polychrome Long Neck Jar with 30 Feathers (1980s)

1 × $ 325.00

Vigil, Minnie - Polychrome Long Neck Jar with 30 Feathers (1980s)

1 × $ 325.00 -

×

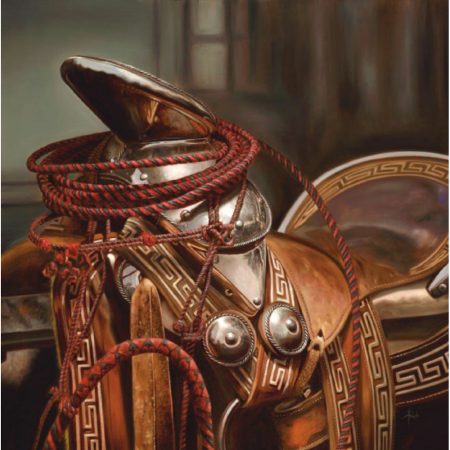

Roda, Andrew - "Cisco Kid", Oil on Canvas, 26"w x 26"

1 × $ 8,200.00

Roda, Andrew - "Cisco Kid", Oil on Canvas, 26"w x 26"

1 × $ 8,200.00 -

×

Gutierrez, Julie - Seedpot with Flowers

1 × $ 150.00

Gutierrez, Julie - Seedpot with Flowers

1 × $ 150.00 -

×

Tafoya, Camilio - Large Seedpot with Rabbit Hunters (1973)

1 × $ 800.00

Tafoya, Camilio - Large Seedpot with Rabbit Hunters (1973)

1 × $ 800.00 -

×

Gonzales, John - Bowl with Four Heartline Bears and Turquoise (1994)

1 × $ 775.00

Gonzales, John - Bowl with Four Heartline Bears and Turquoise (1994)

1 × $ 775.00 -

×

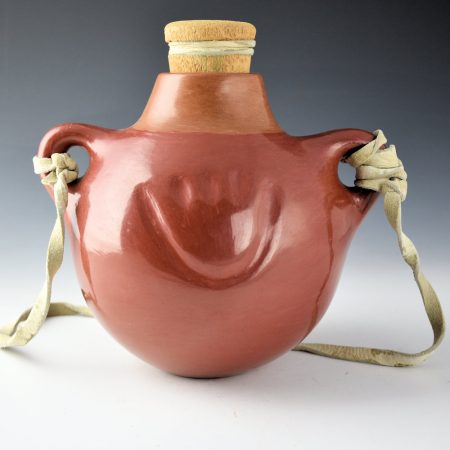

Tafoya, Margaret - Red and Tan Canteen with Bear Paws (1980s)

1 × $ 7,000.00

Tafoya, Margaret - Red and Tan Canteen with Bear Paws (1980s)

1 × $ 7,000.00 -

×

Manygoats, Larrisena - Bowl with Horned Lizard and Basket Design

1 × $ 90.00

Manygoats, Larrisena - Bowl with Horned Lizard and Basket Design

1 × $ 90.00 -

×

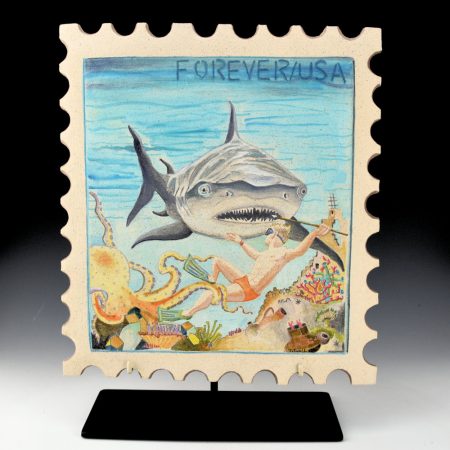

Folwell, Susan - "Danger of the Deep" Forever Stamp Clay Tile Series

1 × $ 1,650.00

Folwell, Susan - "Danger of the Deep" Forever Stamp Clay Tile Series

1 × $ 1,650.00

Collector's Corner

CANNON BEACH: Beyond Nature’s Beauty

Cannon Beach is one of the most beautiful places on the Oregon Coast. Because of its proximity to Portland, which is a seventy-nine-mile drive that takes about an hour and a half to two hours, this beach town is popular with day-trippers, tourists, and those who own or rent beach houses. In a sense, it is the Oregon version of the Hamptons on New York’s Long Island. It is definitely high-end. Despite its being pricey, people flock to Cannon Beach for its natural beauty. However, long before it became a beach mecca for those wanting to escape the big city as well as an arts colony, the area was home to Native Americans who lived off the natural bounty provided by the land and the ocean. When the Lewis and Clark Expedition arrived in the area in the early 1800s a Tillamook village called NeCus’ stood in the area that, in less than 100 years, would see the emergence of what would become today’s resort town of Cannon Beach. However, for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, various Native tribes lived along the Oregon Coast and NeCus’ was a crossroad where various tribes interacted.

According to archaeological evidence and oral history, the ancestors of the Tillamook inhabited this beachside land since the 1400s. The Clatsops, a neighboring tribe, lived approximately thirty miles to the north and frequently visited NeCus’ to trade, socialize, and intermarry. Until the mid-1800s, in addition to the Salish speaking Tillamooks, Oregon’s northern coast was also inhabited by a wide range of Chinook speaking peoples. The area was part of an expansive trade network, which extended inland to the Columbia River as well as to The Dalles and even beyond. Members of the coastal tribes lived in cedar plank longhouses, which often sheltered extended families. Their skill in canoe-making allowed them to travel up and down the coast as well as inland via numerous rivers. Because of the area’s bountiful natural resources and their ability to travel far inland, the coastal tribes had a high standard of living. When the Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered the Native people of the Oregon Coast in 1806, William Clark described them as “mild with good sense, loquacious and inquisitive, king traders that held their own with the expedition.” However, Lewis and Clark were not the first to encounter the tribes of the Oregon Coast. The first contact took place in 1788 when Captain Robert Gray sailed a trade fleet along the Oregon coast. During the 1800s Russian traders also had intermittent interactions with Oregon’s coastal tribes. However, long before these events, Oregon’s Native people’s encounters with Europeans and Euro-Americans arrived on their coast as traders, fur trappers, woodsmen, and even survivors of shipwrecks. These newcomers unknowingly brought their diseases with them.

Thus, smallpox, malaria, the common cold, and many other illnesses were introduced into the Native populations, which had no immunity to these diseases. The results were catastrophic. From the late 1700s to the mid-1800s, epidemics frequently ravaged the Oregon Coast, which reduced the tribal populations significantly. It has been estimated that European diseases wiped out ninety to ninety-five percent of the Native population.

In 1841, Oregon Trail settlers, as they have come to be known, arrived on the Oregon Coast. This resulted in conflicts over land and resources as well as the outright murder of the Natives, further decimating their numbers. In 1856, more than twenty coastal tribes were forcibly relocated to the Siletz Reservation, which was established by executive order of President Franklin Pierce.

Within a relatively short period of time, life on the north Oregon Coast was transformed. Where once Native villages once stood up and down the coastline, this was no longer the case. By the mid-1800s, these villages, which were the site of feasts, rituals, trading, marriages, and other social events, were no more. Such communities were once found in what is now Cannon Beach as well as to the north and south.

In the late 1800s, a settler village was constructed near the beach were the Native village of NeCus’ had once stood. It was called Elk Creek. In 1898, a cannon was recovered from a shipwreck and position in the area of what is Arch Cape, which is located between present-day Cannon Beach and Manzanita. In 1910, another post office was opened and it was called Ecola. However, the U.S. Postal Service required that the name be changed in 1922 because it was causing confusion since it was too similar to the Eola Post Office near Salem, Oregon. It was then decided to change the name of Ecola to Cannon Beach.

Today, the town’s Native history is all but unknown. Once nearby dense forests of fir, pine, spruce and cedar offered coastal tribes building materials; the coastal plains abundant game, berries, and edible roots; the rivers, streams, and lakes provided salmon, sturgeon, trout and other freshwater fish; and the ocean offered halibut, rockfish, cod, sole as well as shrimp, crabs, claims, and mussels. Built mostly on landfill, Cannon Beach is the playground of affluent beach enthusiasts, artists, and tourists, its Indigenous history all but forgotten. Rated as “one of The World’s 100 Most Beautiful Places” by National Geographic Magazine in 2013, it is no surprise that tourists, day trippers, weekenders, renters, and homeowners flock to Cannon Beach for its spectacular natural beauty as well as for its plethora of restaurants, art galleries, and a wide variety of one-of-a-kind shops.

Of course, for the modern visitor, Cannon Beach’s biggest draw is its gorgeous sandy beach, stretching nearly four miles north and south of downtown. At night, the beach in front of numerous properties is illuminated by scores of bonfires as visitors enjoy sunset and beyond.

This section of Oregon’s coastline is noted for its dramatic rock formations, the most specular of which is Haystack Rock, standing 235 feet tall. One of the area’s most famous landmarks and an icon of Cannon Beach, twice a day when the tide is out, scores of people gather around the intertidal pools at the base of this monolith to observe barnacles, crabs, mussels, and colorful sea stars and giant green anemones. High above on the massive rock Tufted Puffins, Western Gulls, Pelagic Cormorants, and Pigeon Guillemots fly about, their cries carried on the wind. Other birds that might be seen at Haystack Rock include Black Oystercatchers and Harlequin Ducks while occasionally Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons visit to prey on the vast number of birds that nest on the rock. Though highly unusual, a cougar visited Haystack Rock in July 2023, probably in search of prey.

Beyond the breathtaking scenery, high end lodgings, and great seafood, Cannon Beach can offer rich historical rewards for the inquiring visitor. All one has to do is to make a little effort.

Sadly, the rich history of Cannon Beach has been obscured by the paraphernalia of contemporary life. However, place names are reminders of the first inhabitants of Cannon Beach – Ecola, Neacoxie, Necanicum, Skipanon, and Clatsop. For anyone willing to take the time to inquire, there is a great deal to uncover about the first inhabitants of Cannon Beach. Doing so is well worth the effort.

Except where noted, all photographs are by E. J. Guarino.

Note: See also the following:

“Just Below the Surface: Life on the Oregon Coast Before Westward Expansion,” June 1, 1919.

“Digging Deeper: More About Life on the Oregon Coast Before Westward Expansion,“ February 25, 2023.

Borts-Medlock, Autumn - Golden Skies "Chaco Parrot", 12/35

Borts-Medlock, Autumn - Golden Skies "Chaco Parrot", 12/35  Cain, Billy - Bowl with Carved Avanyu (1980s)

Cain, Billy - Bowl with Carved Avanyu (1980s)  Baca David - Red 32 Rib Melon Jar

Baca David - Red 32 Rib Melon Jar  Madalena, Reyes - Jar with Lightning Designs

Madalena, Reyes - Jar with Lightning Designs  Vigil, Minnie - Polychrome Long Neck Jar with 30 Feathers (1980s)

Vigil, Minnie - Polychrome Long Neck Jar with 30 Feathers (1980s)  Roda, Andrew - "Cisco Kid", Oil on Canvas, 26"w x 26"

Roda, Andrew - "Cisco Kid", Oil on Canvas, 26"w x 26"  Gutierrez, Julie - Seedpot with Flowers

Gutierrez, Julie - Seedpot with Flowers  Tafoya, Camilio - Large Seedpot with Rabbit Hunters (1973)

Tafoya, Camilio - Large Seedpot with Rabbit Hunters (1973)  Gonzales, John - Bowl with Four Heartline Bears and Turquoise (1994)

Gonzales, John - Bowl with Four Heartline Bears and Turquoise (1994)  Tafoya, Margaret - Red and Tan Canteen with Bear Paws (1980s)

Tafoya, Margaret - Red and Tan Canteen with Bear Paws (1980s)  Manygoats, Larrisena - Bowl with Horned Lizard and Basket Design

Manygoats, Larrisena - Bowl with Horned Lizard and Basket Design  Folwell, Susan - "Danger of the Deep" Forever Stamp Clay Tile Series

Folwell, Susan - "Danger of the Deep" Forever Stamp Clay Tile Series