Collector's Corner

ECLIPSED: The Graphic Art of Tikituk Qinnuayuak

After more than thirty years of collecting Native American and Inuit art, I can honestly say that it is not about how much I can amass. For me, the great joys of being a collector are the thrill of meeting artists whose work is in my collection and frequently becoming friends with them, and discovering the work of an artist that is totally unknown to me. One such example is Inuit artist Tikituk Qinnuayuak. I had never heard of him and had never seen any of his art. That changed when I saw a number of his prints and drawings. I was fascinated by this artist who could create realistic images on the one hand and on the other those that were quite dreamlike and surrealistic.

I wanted to know more about Tikituk Qinnuayuak, but relatively little has been written about him. However, this much is known: Tikituk was married to Lucy Qinnuayuak; it was an arranged marriage when Lucy was still a teenager; Lucy and Tikituk had nine children, only four of which reached adulthood; the couple also adopted two children and took care of the five orphaned children of Tikituk’s brother, Niviaqsi; Tikituk and Lucy mostly led a traditional nomadic life, finally settling in Cape Dorset; Tikituk was a sculptor and a graphic artist; Lucy also became involved in the Cape Dorset arts program and gained renown for the thousands of scenes she created depicting the role of women in traditional Inuit culture as well as stylized images of Arctic birds. Although the work of Lucy Qinnuayuak and others of Tikituk’s generation became well-known, his did not.

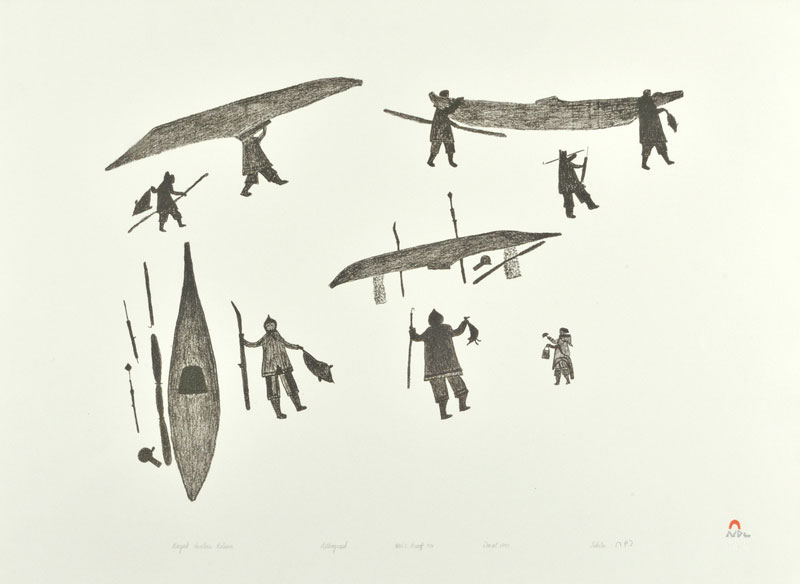

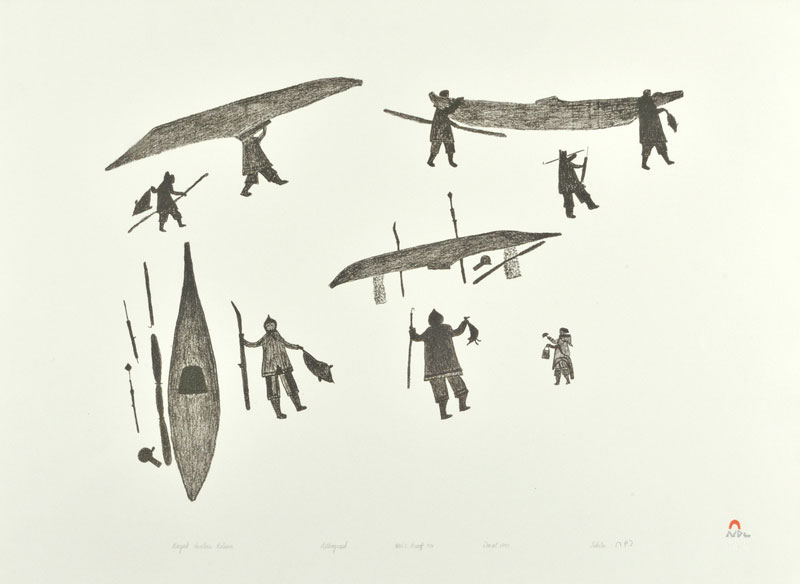

Kayak Hunters Return by Tikituk Qinnuayuak, Cape Dorset, Kinngait, lithograph, 22” x 30” (1990). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

The first images I saw of Tikituk’s work were highly representational – hunters, people walking to camp, caribou, and birds. For the most part, these works are straightforward. Among them is Kayak Hunters Return in which kayaks are being brought back to the land after a hunt at sea. Some of the kayaks are right side up while others are upside down; a number of the hunters’ weapons have been placed on the ground next to one of the kayaks, while others have been leaned against another of the vessels. However, most of the hunters stand with a weapon in hand. Four of the men hold what could be their catch. On the other hand, some may be carrying an avataq, an air filled seal bladder used to prevent catches from sinking. The figures in the print are of various sizes, perhaps suggesting distance. However, in general, Inuit graphic artists do not rigidly adhere to realistic perspectives. The smallest figure in the print is a woman, which may suggest that the male hunters were regarded as the most important persons in traditional Inuit society.

Composition (Three Figures) by Tikituk Qinnuayuak, Cape Dorse(Kinngait), graphite and ink, 20 1/8” x 25 3/4” (1991). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

At first glance, Composition (Three Figures) appears straightforward and innocuous. However, upon closer examination, things may not be quite what they seem. The work has a mysterious, surreal quality.

In the background stands a man holding a hunting tool. He appears to have no obvious relationship to the man and woman in the foreground who seem to float, their feet pointing downward. These figures may, at first, be assumed to be a husband and wife. However, that might not be the case. Although the male is in the center of the drawing, the viewer’s eye is drawn to the image of the woman who is holding a club and pulling her hair. Her face has a disturbing, frightened expression, her mouth drawn into what appears to be a forced smile. The man, however, looks as if he is actually smiling. Although he is wearing Inuit clothing he also has on a cap that is of European origin. This may be a clue as to whom the figure represents. He may be a whaler who has donned Inuit clothing for warmth. The difference in expressions between this man and the woman in the drawing may suggest what has taken place: The woman may have just been traded by her husband for supplies. Inuit women were often forced into marriage and had no say when their favors were bartered by their husbands to White men in exchange for goods. Europeans were fascinated, titillated, and scandalized by Inuit mores, which did not promote monogamy; exchanging one’s wife for needed supplies was simply considered practical and merely an exchange of goods.

Whether or not this interpretation of Composition (Three Figures) is correct is obviously open for debate. Generally, works are sent south without titles from Arctic communities to galleries where they are either labeled as “Untitled” or given a title by gallerists.

My New Handbag by Tikituk Qinnuayuak, Cape Dorset (Kinngait), /50 lithograph, 22.25” x 15” (1991). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

My New Handbag is another intriguing work by Tikituk Qinnuayuak. Based on the title, one would assume that the theme is rather mundane. As is frequently the case with Tikituk’s work, there is more going on than the viewer might, at first, realize. As he was often wont to do, Tikituk includes odd elements in what otherwise appears to be a rather ordinary situation. In My New Handbag a woman is either receiving a handbag as a gift from a man or she may be proudly showing it to him. Curiously, however, a female face appears on the front of the pocketbook. The viewer is left to wonder if the image is that of the woman’s face that is somehow being reflected or if it is the result of something supernatural. That is only one of the strange aspects of this print.

The two figures in My New Handbag have strangely elongated bodies, which adds to the peculiarity of the print. However, in addition to her odd shape, the female has an unusual hairstyle that, combined with the position of her face, resembles the body of a fish. Could Tikituk be suggesting that she is the sea goddess Sedna in human form? There is no way of knowing, but the fact that My New Handbag has so many unusual aspects makes it fascinating.

Composition (Man Dreaming of Animals) by Tikituk Qinnuayuak, Cape Dorset (Kinngait), graphite. 20” x 26” (1959-69), verso top right ‘TIK’. Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

Although Composition (Man Dreaming of Animals) is the accepted title, I have also seen this work listed as Composition (Man Dreaming of Bears), suggesting that the gallerist who titled it did not really look closely at the work. Although there are, in fact, three bears in the drawing, the animal that is at the top of the page is most definitely not a bear. Since Inuit artists generally do not title their work, though rare, mistakes on the part of gallerists do happen, especially if the person doing the titling is not familiar with Arctic animals. The fourth animal in Composition (Man Dreaming of Animals) could possibly be a seal or sea lion. However, based on the length and shape of the tail, that seems doubtful. The creature is more likely a sea otter.

The bear at the bottom right of the page is unexpected. It is standing, humanlike, on two legs, which bears can do for short periods, but it has been drawn much smaller than the other bears. This might suggest that the figure is a bear spirit rather than an actual bear. The discrepancy of size might also be the artist’s way of suggesting the distance of this bear in relation to the other animals.

Floating serenely in the middle of it all is a man with a smile upon his face. One can only conjecture that he is a hunter and is happily dreaming of the animals he pursues. Overall, Composition (Man Dreaming of Animals) has an ethereal quality bordering on the surreal. It is yet another of Tikituk’s works that causes the viewer to pause and ponder.

It is unfortunate that Tikituk Qinnuayuak’s work is not as well known as it deserves to be. Not only did he produce captivating realistic works, he also created more than a few that are quite cryptic and require the viewer to be more than just casually engaged. Although he did not achieve the fame of his wife Lucy Qinnuayuak or others of his contemporaries such as Kenojuak Ashevak and Pisteolak Ashoona, nonetheless Tikituk is an important and unique voice among Inuit artists. His work deserves to be seen and appreciated by collectors, curators, and the public. It is hoped that this happens sooner rather than later.