Collector's Corner

EVEN AFTER I AM DEAD: The Graphic Art of Pitseolak Ashoona

Known simply by her first name to curators and collectors worldwide, Pitseolak Ashoona typifies the first generation of Inuit artists: she had been born on the land; had lived nomadically for many years; and only became an artist late in her life. Born in 1904, Pitseolak spent her childhood moving from camp to camp. She married a man named Ashoona and bore seventeen children, only six of whom survived to adulthood. When her husband died during an epidemic at age forty, Pitseolak, determined to provide for her family, traveled over 100 miles through the Arctic landscape with her six children to Kinngait (Cape Dorset) where she settled and eventually taught herself to draw. In the early 1960s residents of Cape Dorset were introduced to drawing and printmaking, particularly the process of creating stone cuts. “To make prints is not easy,” Pitseolak was quoted as saying in Pitseolak: Pictures Out of My Life, an illustrated biography of the artist. “You must think first and this is hard to do,” she continued. “But I am happy doing the prints. After my husband died I felt very alone and unwanted; making prints is what has made me happiest since he died. I am going to keep on doing them until they tell me to stop. If no one tells me to stop, I shall make them as long as I am well. If I can, I’ll make them even after I am dead.“

By the 1970s Pitseolak was world-famous for her prints and drawings, which portrayed Inuit life before contact with Europeans. Much of Pitseolak’s work is autobiographical, depicting the “old ways” and drawn from early childhood memories. Along with images of life, as it was once lived on the land, Pitseolak also produced works populated by demons, spirits, and monsters, which have a dreamlike quality. Even her realistic works often contain elements of the surreal. Her work appeared in every Annual Cape Dorset Print Collection from 1960 until her death in 1983.

Pitseolak Ashoona was among the first generation of modern Inuit artists who, when given paper and crayons, were simply told to put down on paper whatever came into their head. These artists had no outside influences and no preconceived notions about art. In fact, Inuktitut, the Inuit language, has no word for art. Instead, Inuit use the word isumanivi, meaning “your own thoughts” or “whatever comes to mind”.

In 1996, shortly after I first encountered Inuit art, I acquired Mother and Children, aka Untitled (Woman with Changelings), which I found delightfully strange.

Mother and Children by Pitseolak Ashoona, engraving on paper, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 31/50, #40 in the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection, 12 5/8” x 18 1/8” (1962). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Arctic Artistry Gallery, Chappaqua, NY, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto

At first glance Mother and Children seems to be a portrait of a woman holding her two offspring. On closer inspection, the mother, whose mouth is twisted in what could be a smile or a scream, is struggling to hold on to her two offspring who appear to be only part human. Their lower bodies are covered with fur, which may or may not be clothing. There is a deliberate note of ambiguity in the imagery. Is the work a representation of shamanic transformation or a wry

comment on motherhood? Perhaps it is both. Adding to the surreal quality of the work is the fact that the figures seem to “float” on the page.

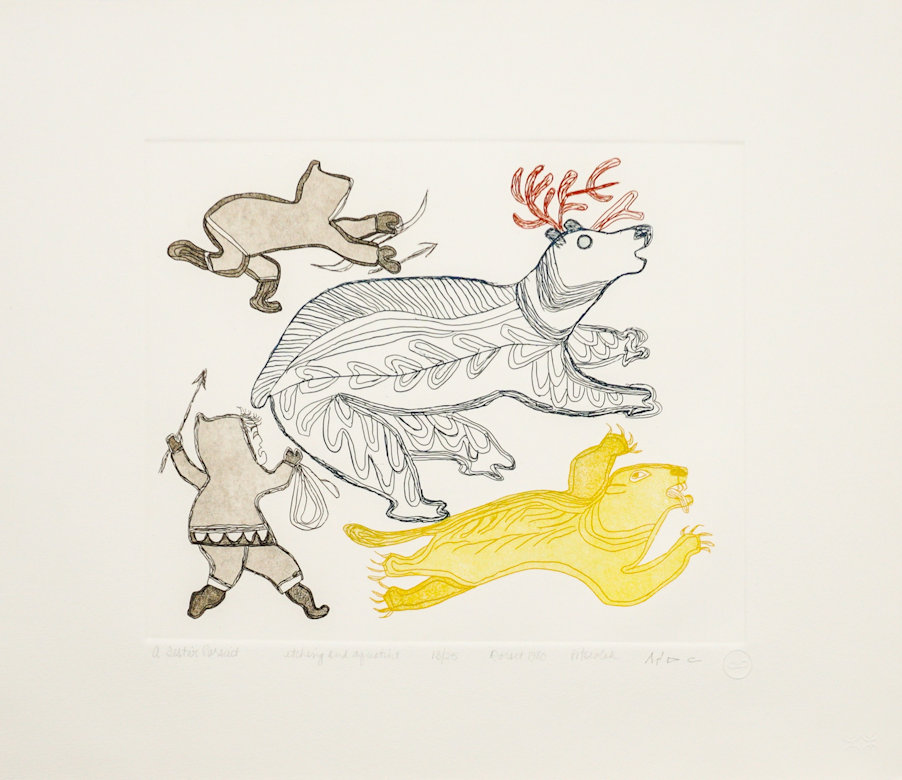

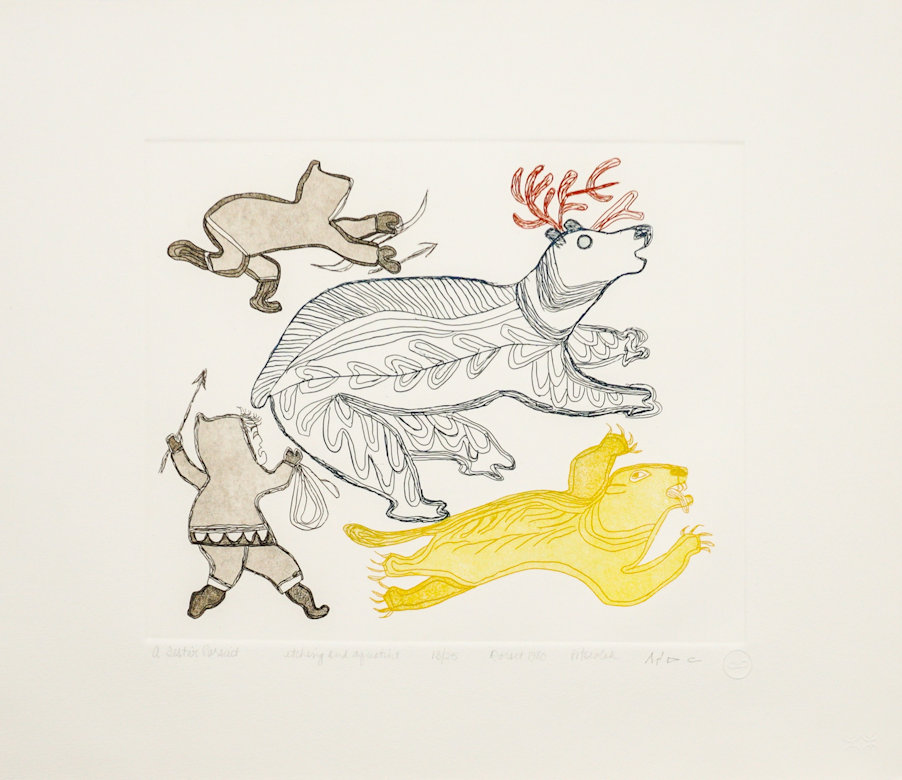

A Festive Pursuit by Pitseolak Ashoona, ed. 13/25, etching & aquatint15 1/2” x 18” (1980). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

In A Festive Pursuit, Pitseolak has again combined the realistic and the fantastic to produce a delightful and somewhat surreal work of art. The hunters in the scene are in pursuit of an animal that seems to be covered in tattoos. This creature looks like a bear with antlers. Lying nearby is what appears to be a yellow bear. (There are, in fact, yellow polar bears in the Arctic whose fur has been discolored by pollution.) This strangely colored animal may also represent the spirit of the strange tattooed beast. As with much in Pitseolak’s work, what the imagery ultimately means is open to interpretation. It is important that the work is titled A Festive Pursuit because, in past times, the killing of large animals, such as caribou and bear, meant food and clothing for the hunters and their families. Animals were not killed simply for sport and bringing down a large animal such as a caribou, seal, walrus, or whale ushered in a time of plenty, which didn’t last for very long. For well into the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Arctic peoples alternated between feast and famine. In A Festive Pursuit, Pitseolak chose to depict what appears to be a successful hunt. This was a happy memory for the artist. It was a time of communal feasting when no one, not even the sled dogs, went hungry.

Hide and Seek by Pitseolak Ashoona, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), ed. 13/25 etching & aquatint, 16” x 18” (1980). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Pitseolak’s representations of her childhood memories of life as it was once lived on the land made her work popular with Canadian, American, and European collectors who saw such depictions as somehow exotic and romantic. Later generations of Inuit graphic artists have sought to de-romanticize and demystify life in the Arctic. Hide and Seek shows a game popular with children the world over. Amid a dry, barren landscape stand skin tents and fish or, perhaps, pelts drying on wooden racks. Two children and their dog are lying in the foreground. Where are the other children? It is necessary for the viewer to look carefully at the openings in the tents in the background. To the right, standing on a mound is a creature that seems to be sticking its tongue out. Perhaps it is a bird, or it may be one of Pitseolak’s fantastical creations added for humor. It is such details that make Pitseolak Ashoona’s work so enjoyable.

The print has been rendered in shades of brown, adding to the work’s nostalgic tone, which is reminiscent of old sepia photographs. The little dog, the bird-like creature, and the drying fish stand out because they are white. Through Pitseolak’s remembrances, so carefully presented in Hide and Seek, the viewer is given a window into what life was like in the Arctic in the early part of the twentieth century.

Snow House of My Youth by Pitseolak Ashoona, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), ed.13/25, etching & aquatint, 18” x 20” (1980). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

With Snow House of My Youth Pitseolak once again returns to her memories. By the time she created this print, Pitseolak had lived in Cape Dorset for some twenty years and was living in a Western-style house. However, the print evokes a time when she was living a nomadic lifestyle. Snow houses (igluvijaq in Inuktitut,) were constructed during the long winter months and could house one or more families. A snow house is surprisingly warm since the flame from a qulliq (also written as kudlik), or oil lamp and even just the body heat of the occupants can keep the home comfortably heated. These structures were also built by hunters who traveled long distances and the word iglu (Igloo in English) refers to a shelter made of any material.

Snow House of My Youth is rich in details. There is a dead seal atop blocks of snow, which a dog is trying to reach; another dog is jumping up against other blocks of snow; two men are working on their fishing gear, and there is a woman with a child in her amauti (parka). The scene is lovingly rendered as befits a cherished recollection.

During her lifetime, Pitseolak produced nearly 9,000 drawings, 233 of which were made into prints. However, despite producing so many drawings, Pitseolak is best known for her prints. There is a simple reason for that. Until fairly recently, Inuit drawings had one purpose: to be the basis for prints. Whether selected to be made into a print or not, very few drawings were available to museums and collectors. Instead, they were archived. Those from Cape Dorset were placed at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario where they could be photographed, documented, and exhibited. A relatively few of Pitseolak’s drawings, which were created to be the basis for her prints, have been released to galleries for sale. It has only been within that last twenty-five or so years that Cape Dorset drawings have been created for their own sake. In that time, they have garnered a large collector base thanks to the efforts of gallerists Patricia Feheley, owner of Feheley Fine Arts in Toronto, and Robert Kardosh, director/curator at the Marion Scott Gallery in Vancouver. In addition to her own creative legacy, Pitseolak Ashoona was the matriarch of an artistic dynasty. She was the mother of several Cape Dorset artists: Ottochie Ashoona, Komwartok Ashoona, Kaka Ashoona, Kiawak Ashoona, and Napatchie Pootoogook as well as the grandmother of famed contemporary artists Annie Pootoogook, Shuvinai Ashoona, and Siassie Kenneally. For the residents of Cape Dorset and among collectors of Inuit art, Pitseolak Ashoona is one of the most revered artists.