Collector's Corner

GLOBAL AWARENESS: Artist Qavavau Manumie Looks Beyond His Kinngait Home

Though geographically isolated on Dorset Island in Nunavut, Canada, the small hamlet of Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset) is known worldwide for its artistic output and many of its artists are so celebrated that collectors and curators simply refer to them by their first name. Qavavau Manumie (also written as Kavavaow Mannomee and Qavavau Mannomie) is among the Kinngait artists whose work has an international collector base. Although Manumie is probably best known for complex works that are fanciful, somewhat surreal, and often populated by tiny persons resembling elves, his large body of work reflects a wide range of interests and themes: Inuit myths and legends (often presented in a humorous way); scenes of contemporary Inuit life; images of Arctic wildlife; whimsical works portraying an Arctic world populated by tiny people, known to the Inuit as the Inuralaat; portraits of other Kinngait artists (a little known aspect of the artist’s work); the landscape around Kinngait; environmental issues; and an awareness of international events.

Although Qavavau Manumie’s portraits of other Kiinngait artists are not as well known as they should be, his works that deal with global issues are also relatively unknown.

Starving Ethiopian by Qavavau Manumie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), colored pencil & ink, 12 7/8” x 10” (1995). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

In an interview on May 19, 2020, Qavavau Manumie said the following about his drawing Starving Ethiopian: ”This was about the time when the African people were starving in Ethiopia. The Inuk man is trying to help the man who is dressed in the traditional Ethiopian style. Behind him on a table is food that has been gathered for the starving people.”

Until fairly recently in their history, Arctic peoples were isolated from what was happening outside the area in which they lived. Radio brought in some information, but it was TV that became a window to the rest of the world and, of course, later the Internet. During the 1990s Qavavau Manumie became aware of the famine in Ethiopia through humanitarian aid TV commercials. Although the worst of the famine occurred between 1983 and 1985, Ethiopia’s people continue to be stalked by hunger. Inuit communities, having experienced famine themselves less than a generation before, donated heavily to the cause.

Qavavau Manumie was so moved by the plight of the Ethiopians that he created a drawing about it. Although the imagery of Starving Ethiopian is disturbing, it is also tender and compassionate, reflecting our common humanity: An Inuk man looks at the emaciated and nearly naked Ethiopian he holds in his arms.

The Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster by Qavavau Manumie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), colored pencil & ink, 20” x 26” (1995). Private Collection. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

The Challenger disaster occurred on January 28, 1986. It was a shocking event. A large portion of the world’s population looked at their TV screens in horror when, seventy-three seconds into its launch, the Space Shuttle broke apart. All seven crew members were killed. For many, what was particularly touching was that one of the crew was a civilian – a humble middle school teacher. NASA’s Teacher in Space Project was looking for a gifted teacher who would communicate with students during the Space Shuttle’s orbit and, from more than 11,000 applicants, Christa McAuliffe was chosen to be the first civilian to fly into space.

Nine years later, Qavavau Manumie was inspired to create The Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster, a drawing about this tragic event. In the same interview conducted on May 19, 2020, Manumie said the following regarding his drawing about this tragedy, “This is about the American space shuttle that broke apart and crashed in 1986. There were seven astronauts on board who were killed, and so there are seven crosses in the drawing to mark the graves.” The imagery Manumie chose is simple but powerful: mountains (representing Earth); the Challenger Space Shuttle taking off; an American flag; seven crosses symbolizing the seven lost astronauts; and, above it all, Jesus, beams of light emanating from his head, standing with open arms and holding a cross.

On September 11, 2001, the world was again shaken, this time by attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City in which 2,763 people died. Although he lives 1,622 miles from Manhattan, Qavavau Manumie was once again moved to respond artistically with two drawings: Composition (World Trade Center Homage) and Composition (World Trade Center Homage with Birds). I contacted Pat Feheley, owner of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, for comment on these two striking drawings. “Qavavau Mannomie has always been interested in global events,” she stated. “Best known for his images depicting climate change and environmental issues in the Arctic, he has also referenced important international events, such as the 9/11 bombings in New York City.”

Composition (World Trade Center Homage) by Qavavau Manumie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), colored pencil & ink, 20” x 26” (2001). Private Collection. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Composition (World Trade Center Homage) shows the moment when the second plane is about to fly into the South Tower of the World Trade Center; the North Tower has already been hit. The three crosses represent those who were killed while the American and Canadian flags reflect the close ties between the two countries as well as the fact that at least twenty-four Canadians died in the attack on the World Trade Center. Pat Feheley further commented on Composition (World Trade Center Homage): “ Shortly after this disaster, Qavavau Manumie did a series of drawings of the buildings such as this one. One tower is on fire and a plane is aiming for the second tower. In the foreground, three graves signal the tragic loss of life on that day. While this drawing is true to the event, he also did a series of drawings in which the planes turned into birds and veered off, missing the buildings. This is typical of the artist as he does not turn away from stark depictions of death but often will imagine a more optimistic world.”

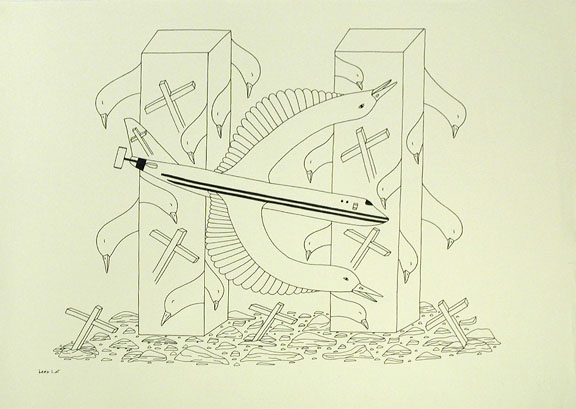

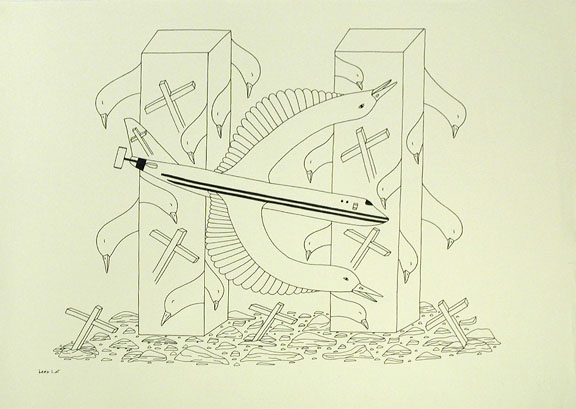

Composition (World Trade Center Homage with Birds) by Qavavau Manumie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), ink, 20” x 26” (2001). Private Collection. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Qavavau Manumie is considered an expert on birds and frequently includes them in his prints and drawings. Some are transformation scenes while others are explorations of abstraction, using bird forms as his inspiration. In Composition (World Trade Center Homage with Birds) Manumie uses birds in a number of ways: the plane’s wings are birds, suggesting the souls of those lost in the disaster are being taken to heaven; there are birds on the two buildings, some seem to have wrapped themselves around each tower, while others appear to be looking downward. These, too, may suggest the souls of those who were lost on 9/11. Both of the towers bear crosses and their angle may suggest the people who were forced to jump from the buildings. On the ground in front of the towers, there are three more crosses, again symbolizing those who died in the 9/11 attack.

The fact that Qavavau Manumie created multiple drawings about the attack on the World Trade Center is a clear indication that he was deeply moved by this event.

Despite living in a hamlet with a population of under 1,500 and geographically isolated from most of the rest of the planet, Qavavau Manumie is deeply affected by events in other parts of the world. Remoteness has not prevented Manumie from expressing his concern for his fellow humans through his art. Such works defy the assumptions of many collectors who expect Inuit art to present iconic images of Arctic wildlife or a romanticized version of life as it was once lived on the land. Rather than reinforce such outmoded ideas, Qavavau Manumie’s work reflects the concerns and interests of a 21st-century artist.

The author would like to thank Pat Feheley, owner of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Elyse Jacobson, gallerist at Feheley Fine Arts, for their invaluable help with this article.