Collector's Corner

FROM THE HEART OF THE SEA: The Ceramic Art of Courtney M. Leonard

Much of Courtney M. Leonard’s work is a response to the maritime influences that shaped the lives of her ancestors. She is a member of the Shinnecock tribe whose ancestral lands are located on the southeastern shore of what is today Long Island, New York. The 750-acre Shinnecock Indian Reservation is located about 3 miles west of the Village of Southampton, which is one of the richest areas in the United States. The land that is now Southampton, real estate worth billions of dollars, once belonged to the Shinnecocks, but was stolen from them through a forged document in the mid-1800s. In the past, Shinnecock men carved out large trees to make canoes that were sturdy enough to carry them far beyond their island home to Atlantic waters where they fished and whaled.

Ironically, the Shinnecocks, whose name means People of the Stoney Shore, can’t use the local beach (once tribal land) unless they pay $300.00 for a town permit or $40.00 for a one day parking fee. It is from her knowledge of the Shinnecock’s seafaring past that Courtney M. Leonard draws inspiration for her ceramic art.

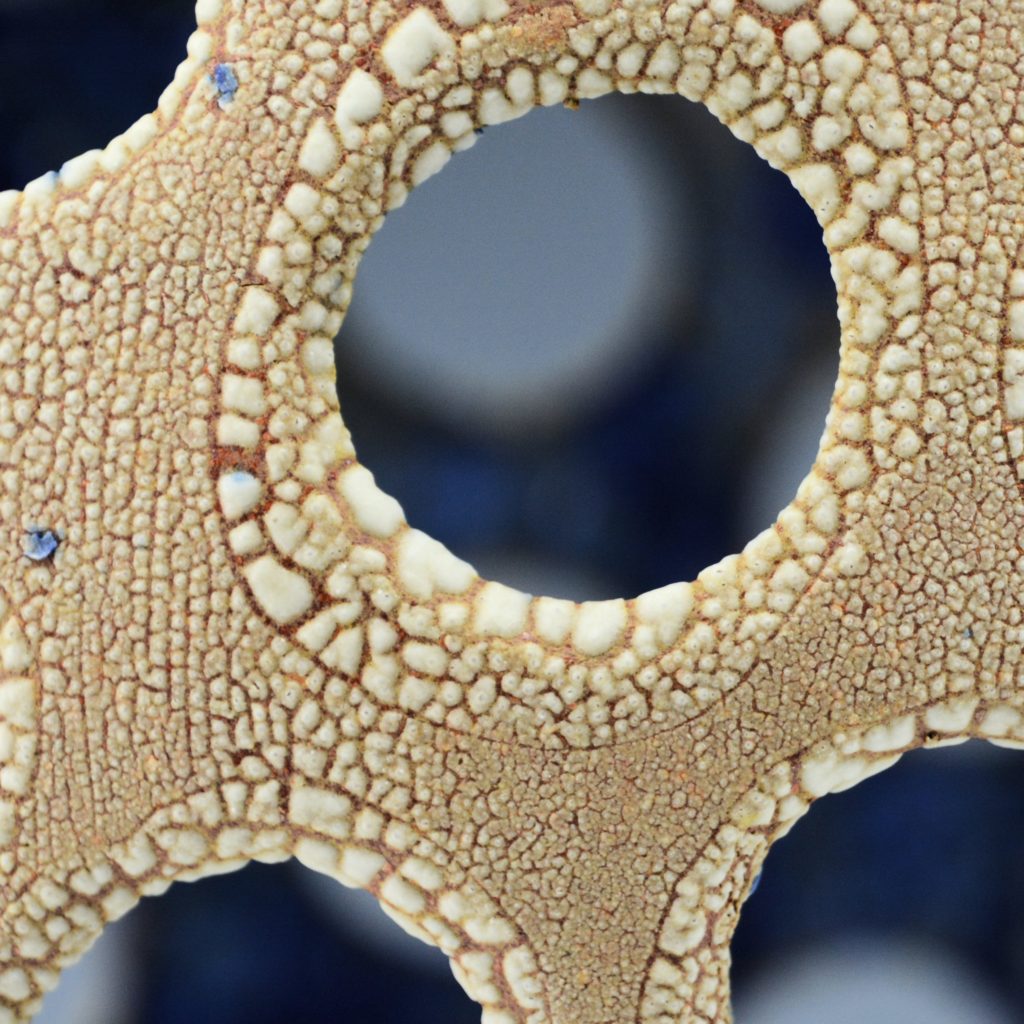

The first time I saw one of the vessels from Leonard’s Breach Series, I didn’t know what to make of it. I had seen ceramics with multiple holes in them before (the work of Hubert Candelario comes to mind), but this was something different. Although I had put a moratorium on buying pottery, since I have so much of it that it is now walking across my living room floor, I couldn’t resist acquiring what I believe is an important work of art. The vessel appears to be made out of coral or bone, giving it a disquieting, yet compelling quality. One of the most fascinating aspects of the piece is that it is designed to sit either on its end or its side, but what intrigues people most is the textual quality of the piece, so much so that they can’t resist touching it. (I’ve had to put a small sign in front of it reading “Do Not Touch.”) According to Charles King, “This multi-holed vessel is inspired by the structures made for reviving coral growth. The use of mica clay can be seen just under the surface of the piece. The surface is created with her own hand-made glazes and the inside is glazed with a blue slip. The mixture of the blue inside and the rough textured surface is striking. . . . The holes actually give the piece a strong structure. This piece . . . is an exploration of historical ties to water and whale; imposed law; and the current relationship of material sustainability.”

The very title of the clay baskets created by Courtney M. Leonard suggest a time of plenty for the Shinnecock people. Unfortunately, those who currently live on the reservation live a meager existence in sharp contrast to their ancestors’ abundance from farming, fishing, and whaling. Leonard’s Abundance baskets, which are in shades of blue, evoke a time when such utilitarian objects might be filled not only with corn and squash, but with fish as well. The blue coloration of these ceramic works also suggest the sea, which was a source of great abundance for the Shinnecocks in the past. “What makes these so dynamic,” Charles King wrote, “are first the glazes she [Leonard] creates. The colors are beautiful and the surface often textural. The way the coils are woven actually creates strong clay vessels. The way they are made they can sit on a surface, or much like they are in the fishing villages, they are hung on the wall when not in use.”

Path We Share is a series of clay sperm whale teeth decorated with various designs. Some teeth have blue and white areas that mimic delft ware for which Dutch colonizers of New York were famous. By referencing these ceramics Leonard acknowledges the Shinnecock’s interactions with the first colonizers of Long Island as well as her ancestor’s renown as whalers.

|

|

Other clay whale’s teeth in the Path We Share Series are allusions to the art of scrimshaw, which was a popular pastime of whalers from between 1745 and 1759 until the ban on commercial whaling in 1982. Scrimshaw consists of pictures and lettering, often highlighted with pigment, most commonly engraved on the bones and teeth of whales. Leonard’s stylized whale’s teeth, created out of clay, pay tribute to the complex connections between her ancestors and those who colonized their land. Charles King has stated that Courtney M. Leonard “has long been exploring those fraught relationships – between Native and non-Native people, between Native people and their traditional practices, and between all people and the natural balance of the world.”

Although I have only recently become aware of Courtney M. Leonard’s art, I find the artist’s exploration of the complicated connections between past and present, Native and non-Native people, environmental sustainability, and the Shinnecock’s historical relationship to water and whaling to be extremely thought-provoking. “Her pottery,” Charles King commented, “is meticulously crafted to contain historical and cultural references, but also to make the viewer reflect on their own relationship with nature and sustainability.” Leonard’s work typifies the best of what constitutes contemporary ceramics – flawless technique combined with a provocative concept.

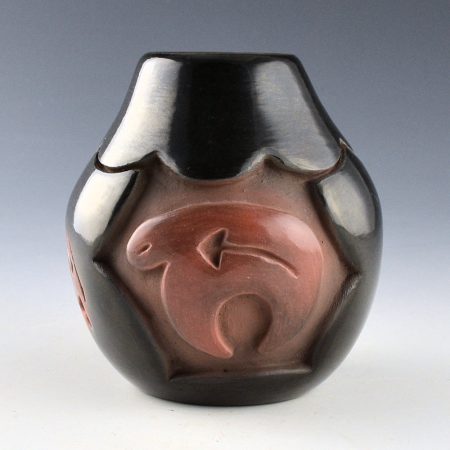

Suazo, Anita - Black and Sienna Jar with Bears and Bear Paws

Suazo, Anita - Black and Sienna Jar with Bears and Bear Paws