Collector's Corner

ISUMANIVI, OR WHATEVER COMES TO MIND: The Graphic Art of Ikayukta Tunnillie

From its inception, a surrealistic strain has run through Inuit art and continues to do so. Such works contain multiple perspectives, distortions, emotional intensity, seeming spontaneity and, often, strange creatures. However, many pieces were given prosaic titles by the co-ops or by gallerists that lend themselves to an anthropological or ethnographic interpretation rather than an artistic one and the artists may or may not have had any input. It should be noted that Inuit artists were not influenced by European Surrealists. It was, in fact, the other way around. Early on, when Inuit artists wondered what exactly they should draw they were told, “Whatever comes to mind,” or isumanivi in Inuktitut. In spite of having collected Inuit Art for almost thirty years, I am still often surprised by what I don’t know. One revelation was the work of Ikayukta Tunnillie, which was totally unknown to me. However, as soon as I saw some of her prints, I was immediately captivated. Her response to the idea of isumanivi is one of the most fascinating aspects of her art. Here was an artist with a unique voice and I knew nothing about her.

Ikayukta Tunnillie was nomadic for most of her life, traveling by dogsled and living in skin tents. In 1970, Tunnillie settled in Kinngait (Cape Dorset). At the time, she was fifty-nine. A year later, Tunnillie was one of the artists whose work was part of the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection. Two of Ikayukta Tunnillie’s children, Kakulu Sagiatuk and Qavaroak Tunnillie, also became artists. Kakulu, one of her daughters had begun drawing in the early 1960s and it was she who encouraged her mother to take it up as well. Ikayukta Tunnillie once remarked, “. . . I can’t really draw very well . . . I can’t draw like the others do.” At the time, she was working alongside Kenojuak Ashevak, Pitseolak Ashoona, Kananginak Pootoogook, Lucy Qinnuayuak, and Kingmeata Etidlooie – all major Inuit graphic artists – so it is understandable that she might feel somewhat intimidated.

Four works by Ikayukta Tunnillie immediately caught my attention: Birds, Birds Around Fox Skin, Timiat Qimiklu (Birds and Dogs), and Catching Birds. These prints typify what has come to be known as the Inuit Surreal and, in addition, they are decidedly humorous. Although the titles of these works might seem mundane, even banal, the works themselves are striking and thought-provoking, revealing the distinctive artistic vision of an artist who was quite humble about her work.

Birds by Ikayukta Tunnillie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), lithograph, Ed. 11/50, 15” x 19” (1978). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Despite its rather commonplace title, Birds is one of Ikayukta Tunnillie’s most intriguing prints. It is certainly not what most people have come to expect from Inuit works on paper and the viewer is hard pressed to fathom this most unusual image. The birds depicted are certainly none that exist in Nature. Clearly, they were conjured from the artist’s imagination. Two birds walk in opposite directions and each has two heads. On closer inspection, the image is even more bizarre. Located in the anal area of each bird is what might be another, unformed head. Then, too, there is something growing out of the space between each bird’s two heads. It appears to be plant-like, but it also resembles an antenna. From each head, as well as the strange shape in the anal area, there appears to be something orange in color dripping out. Tunnillie has used this device in a number of her works, particularly in her 1978 lithograph Feeding Dogs, which makes the meaning clear: it represents either flesh or blood. Birds is a work that is at once disturbing and somewhat humorous.

Birds Around Fox Skin by Ikayukta Tunnillie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), stonecut & stencil, Ed. 35/50, 16 1/2” x 23 3/4” (1979).

Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

What to make of Birds Around a Fox Skin? At first glance, the image is truly strange. In addition to having a whirling quality, the print leaves the viewer wondering if the image represents eight birds or one single bird with eight heads. The use of lines in the print, as well as the printmaking technique of stone-cut & stencil, creates the perception of feathers in the eye of the viewer. In the middle of this image is an orange fox. Again, the viewer is left to ponder the meaning of its placement. Based on iconography Ikayukta Tunnillie used in other works, the orange “drops” at the mouth of each bird head indicate the act of feeding. What the viewer may discern as some sort of droplet may actually represent pieces of flesh torn off the body of the fox. The print may, in fact, represent birds who are surrounding and scavenging a dead fox.

Timiat Qimiklu (Birds and Dogs) by Ikayukta Tunnillie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Ed. 38/50, lithograph, 13 3/4” x 19 1/4” (1978). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Timiat Qimiklu is another of Ikayukta Tunnillie’s prints that is rather perplexing. Once again, the viewer is not quite sure what exactly is being presented and what to make of it. The title of the work was given in Inuktitut and I was curious as to what it might mean so I checked with Elyse Jacobson at Feheley Fine Arts in Toronto. I was not particularly surprised with the response I received since the overwhelming majority of Inuit works on paper have titles that can best be described as mundane. Although the imagery of Timiat Qimiklu is rather strange, the title simply means Birds and Dogs, which isn’t all that helpful in trying to understand exactly what the artist is trying to convey. Each of the birds has an odd tail and what each has eaten seems to appear in its stomach so the viewer can see it. The largest bird has eaten what is possibly a fox; the middle bird has eaten another bird; and the third, perhaps, a fish. Not only are they of varying sizes, but the birds are individually delineated in such a way as to indicate different species. Both the birds and the dogs have Tunnillie’s signature symbol for feeding – an elongated orange drop at their mouth. What is being depicted in the print is most probably based on events that the artist witnessed when she lived a nomadic life on the land. However, it has been filtered through the artist’s idiosyncratic vision, producing a work that is decidedly surreal.

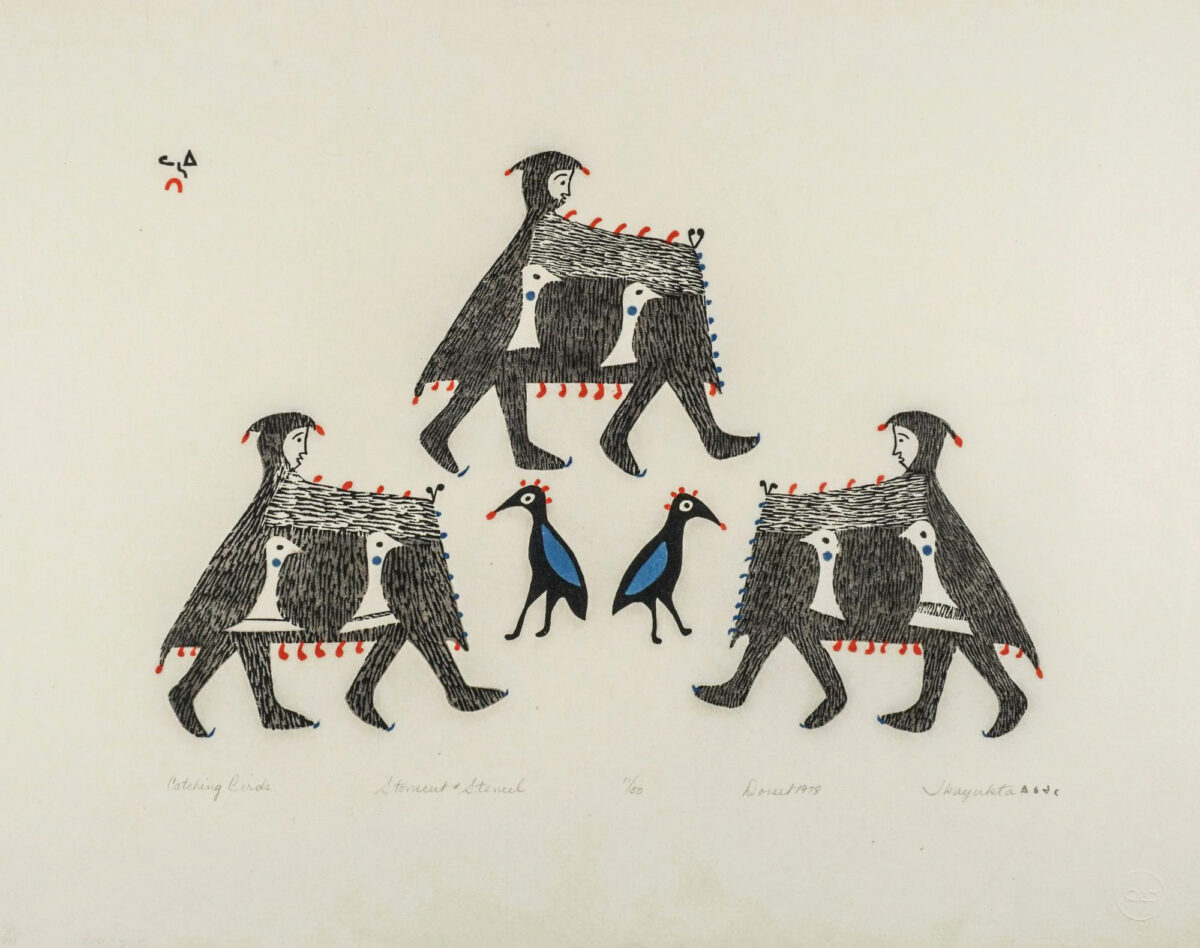

Catching Birds by Ikayukta Tunnilli, Inuit, Kinngait, Cape Dorset, stonecutter & stencil, 22” x 27 3/4” (1978). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

The first time I saw Catching Birds the print brought an immediate smile to my face. The figures struck me as resembling cartoon characters. Each hunter is individualized, though subtly so, and has a rather inscrutable look on his or her face. Catching Birds, like other works by Ikayukta Tunnillie, is both surreal and humorous since the figures appear to have four legs. Of course, the reality of the situation might simply be that two people are hiding under a cloth so as to catch the birds. Another possibility is that the three figures represent different time periods. Inuit artists do not feel constrained with regard to time and space, often depicting events that happened at different times in the same work. This may very well be the case in Catching Birds. Of course, the imagery is most probably based on an event Ikayukta Tunnillie experienced. Nonetheless, she presents it in a fanciful way, forcing the viewer to see the world through her eyes.

I am always delighted when I encounter an artist whose work is totally unknown to me. Looking at the artwork they have produced becomes a voyage of discovery. I had never heard of Ikayukta Tunnillie and came upon her work quite by accident. It was one of those fortuitous circumstances that sometimes happens to collectors. As I studied a number of Tunnillie’s prints I became more and more astonished that she is not particularly well known, though she should be. Modest with regard to her drawing skills, Ikayukta Tunnillie had an uncommon artistic vision: She allowed the world to see her Arctic homeland in a new and unusual way. Tunnillie is a fascinating artist who is worthy of more investigation. While outsiders might refer to some aspects of her art as surrealistic, the artist most probably felt that she was simply drawing whatever came to mind.