Collector's Corner

RE-SEEING THE WEST: Collecting Ledger Drawings

February, 2014

The American West is instantly recognizable to people around the world because, for generations, it has been portrayed in countless works of art. Paintings, novels, plays, operas and, most recently, movies and TV have presented it as a wild and violent place. However, over the last century the West has been seen through decidedly non-Native eyes. As the United States expanded, our nation’s concept of what constituted the West grew as well, pushing farther and farther from the East Coast until reaching the Pacific. Most people tend to get their ideas about the West and about Native Americans from motion pictures and television, which usually present an inaccurate and Eurocentric view. Though not as known or as influential as the mass media, the ways in which Native people have recorded their life experiences from their own point of view do exist – in stone, on hide and, when it became available, on paper.

Although I have been collecting Inuit graphics since 1996, acquiring Native American works on paper has been a relatively recent endeavor. At first, I strictly limited myself to work produced by Pueblo artists but, within a few years, the parameters were expanded to include graphics by artists from a wide range of Native American groups. Without exception, however, all the works I collected were by living artists. That changed when a long delayed wish was fulfilled: I acquired a ledger book drawing.

Rare and often expensive, ledger drawings can be so hard to acquire that adding one to my collection became an idea that I simply put out of my mind. However, in January 2013 I attended the METRO Show in Manhattan, an art fair where scores of galleries from around the country offered ethnographic, tribal, Native American and fine art to a wide range of collectors. I had no intention of buying any art and had just planned to see what was available. That changed when I came to H. Malcolm Grimmer, which was presenting pages from the recently discovered Macnider Ledger Book. Still, I hesitated. Tom Cleary, an associate at the gallery, was kind enough to speak to me at length about the drawings and showed me additional pages from the Macnider Ledger Book that were not on display and, together, we were able to find one that I could afford and, more importantly, one to which I was drawn. I began to realize that this might be the opportunity for which I had been waiting. Mr. Cleary was so personable, knowledgeable and willing to work with me to find a suitable work for my collection that he erased all doubts and I was able to acquire my first ledger book drawing.

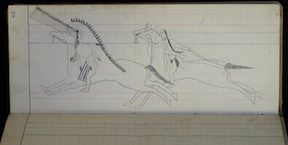

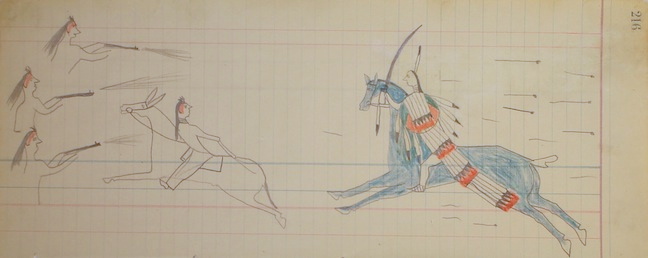

- Galloping Rider Under Fire, a battle scene, Page 51 from the Macnider Ledger Book, Sioux, graphite and color pencil on ledger paper; 14.5”w x 5.75”h (circa 1880). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The drawing I chose is probably not what most collectors would have selected since it lacks a great deal of color, something that is highly prized by those who collect this type of art. Nonetheless, what attracted me was the work’s inherent drama and sense of movement. Although created before the advent of movies, like many ledger drawings Page 51 from the Macnider Ledger Book has a cinematic quality. What Page 51 lacks in color it certainly more than makes up for by the drawing’s sense of action – a lone horseman rides away from his enemies, attempting to reach cover in the vegetation on the left of the page. Partially seen on the work’s right side are the faces of six men who are firing riffles at the fleeing rider. The fact that the figures are mostly obscured from the viewer may be suggestive of an ambush. Who these attackers are is unclear though they are most likely Crow warriors. Below and to the left of the horse are marks representing bullets. They may be those that have missed the rider or may indicate that he may have comrades hiding in the brush, firing back to protect him. In either case, the subject of the drawing’s narrative is galloping through a hailstorm of bullets.

Seeing pages from the Macnider Ledger Book and actually acquiring one of the drawings inflamed my imagination. I wanted to learn more.

When Europeans re-introduced the horse into the Americas Native life changed forever, perhaps nowhere more so than on the Plains. Hunting bison, warfare and migrations now all involved the horse. For Plains Indians the buffalo was Life itself, providing food, clothing, shelter as well as hide “canvases” on which they could express themselves visually. In the 1800s as a means of subduing Plains tribes who refused to submit to the takeover of their ancestral lands, the United States Government encouraged the mass slaughter of the bison. Herds that once numbered in the millions were reduced to less than 200 animals. With the loss of the bison, Plains people were forced onto reservations and leaders were imprisoned, sometimes thousands of miles from their homelands.

With the almost complete demise of the bison, Plains Indians no longer had a medium on which to record the world as they saw it. However, as White settlers and businessmen moved west so did paper, pens, pencils, crayons and watercolors. With access to these new materials, many Plains Indians began to create what has come to be known as “ledger art,” since account ledger books were among the most common sources of paper on the Plains in the 1800s. However, drawings in sketchbooks, albums and on brown paper are also considered ledger art. The antecedents of this new genre were paintings on hide and, earlier, rock art. Traditionally, among Plains Indians females created works with geometric designs while males created representational images. Ledger drawings, which are representational and narrative, were produced exclusively by men. Although scenes of warfare predominate, there are also drawings of hunting parties, courtship practices, religious rituals, as well as of dreams and visions. These artists were not only recording their remembrances of pre-reservation life but also creating works reflecting the changes wrought by the material culture and new technologies brought by European-Americans as they advanced westward. Some of the most coveted drawings are those with images of parasols, trade blankets, metal pots and pans and other non-Native goods. In a short time, ledger books were sought-after by government agents, anthropologists, missionaries and tourists.

Since all three of the ledger drawings I eventually acquired come from the Macnider Ledger Book I became extremely curious about it. In a phone interview, Tom Cleary said that the book was found at the bottom of a box of dictionaries at a small auction held at an informal yard sale. Cleary added that “the naming of ledger books is somewhat arbitrary and often a name is chosen that will make a book stand out.” In the case of the Macnider Ledger book, the name derives from “John Macnider,” which is written on the cover of the book. Mr. Cleary went on to say that research indicates that the Macniders were most likely a family of merchants living in the Dakotas.

I also wondered about who decided whether to keep the pages of a ledger book together or sell them separately. Mr. Cleary said, “It is up to the discretion of the owner as to whether to keep a book intact or sell pages individually.”

Drawn by possibly as many as three Sioux men in the 1800s, the Macnider Ledger Book reflects a time of great change on the American Plains and is, according to Tom Cleary, a “personal narrative of Plains life.” The more I looked at images from this particular book, the more intrigued I became and decided to buy a second drawing. It, too, was an unconventional choice as ledger pages go.

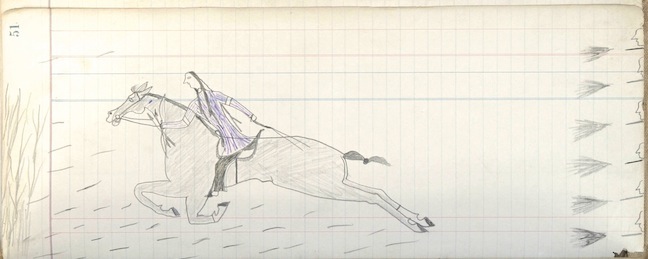

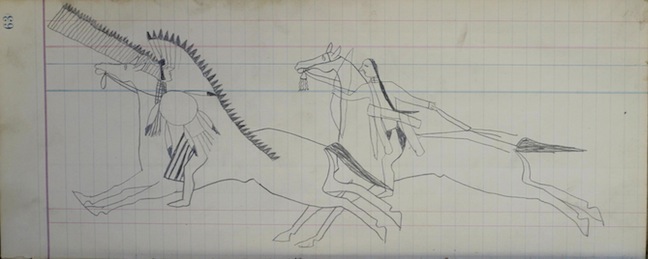

- Page 63 as it originally appeared in the Macnider Ledger Book.

Page 63 of the Macnider Ledger Book is clearly identified as unfinished for a number of reasons. The artist had yet to complete a number of the lines and the work is totally lacking in color. Perhaps more importantly, according to Susan Zeller, associate curator of Native American Art at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the two figures do not have any tribal indicators, especially with regard to the Crow warrior’s shield. Nonetheless, I feel this ledger page is important because it is a work in progress. It shows a ledger artist’s process. I was also attracted to the drama portrayed in the drawing. Even though it is devoid of color, Page 63 is rife with dramatic tension. As part of my collection, it serves as a bridge between the first ledger drawing I purchased, Page 51, and the third I acquired.

When I first saw Page 216 of the Macnider Ledger Book it was marred by a coffee stain but that was subsequently removed by a professional paper restorer, making the drawing much more desirable. As with the first two ledger pages I acquired, Page 216 is extremely dramatic, showing a Sioux warrior pursing his Crow enemy directly into a Crow firing line. According to Tom Cleary in his excellent article “The Macnider Ledger Book: Coloring the Plains,” “Sioux warriors . . . preferred to recount their successful exploits against their archenemies, the Crow. In the Macnider ledgers, the Crow are shown with red faces and their distinctive cow-lick hairstyles. To emphasize their inferiority, they are often depicted with less color. The effect is psychological. Visually, they seem insignificant on the page – particularly when compared to the colorful and elaborately dressed Sioux.”

With three drawings from the Macnider Ledger Book now in my collection I had a number of questions. Having recently seen “Stories Outside the Lines: American Indian Ledger art,” at the Heard Museum North as well has having attended numerous exhibits about ledger art in the past, I wondered if the “action” in all such works always moved from right to left since I couldn’t recall any in which the narrative went from left to right. In an Email correspondence, Tom Cleary stated, “Almost all pictographic scenes in Plains art that I am aware of proceed from right to left. This finds its roots in rock art and was passed down over the centuries through hide painting. Action proceeds leftward.”

My curiosity was also aroused because two, perhaps even all three, of the the drawings I owned seemed as if they could have been produced by the same hand. Once again, I consulted Tom Cleary who said, “I wouldn’t quote myself as having the final word, but I think your pages were done by two or more artists. . . . As ledger scholarship goes, there is some thought that an artist would proceed in one direction through the book (backwards on every odd page, for example). So, the fact that the Macnider book contains drawings at one end (on even pages), a blank middle section and drawings at the other end (on odd pages) suggests, by this logic, the possibility of there being at least two artists involved. You now own pages 216, 63, and 51 – not only are these from different areas of the book, they are also a mixture of odd and even. I think pages 63 and 51, with the elongated horses, SEEM to be by the same hand. Unfortunately, . . . this is merely conjecture on my part.”

As I studied Page 216 and images of other ledger drawings on the Internet, it struck me that often horses were depicted with unnatural colors, such as blue, and wondered why this might be so. Once again, Mr. Cleary came to the rescue. In a phone conversation, he explained that odd color choices may or may not have significance but that it was most likely governed by artistic expression rather than the limited availability of a variety of colors. “Plains Indians did have access to natural pigments,” he said, “so color may have been a conscious choice.” With the arrival of White settlers, crayons, pencils and watercolors afforded Plains artists new materials with which to express themselves. “However,” he added, “in the past, blue and red dyes were not easily accessible so the odd use of these colors may be honoring a tradition and is probably indicative of the mysticism associated with horses and the reverence with which they were regarded by Plains Indians.”

Ledger drawings have always fascinated me because they provide a window into a world so different from my own. Owning ledger pages from the same book has afforded me the opportunity to consider them as works of art in detail and marvel at their artistry. As with artists from every era and culture, those who created what has come to be known as ledger art drew upon their experiences at a time of great change, thereby allowing us to see what they encountered through their eyes. Ideas about the American West have long been established by iconic, though misinformed, images created by European and American artists and by the mass media. Ledger drawings offer us an opportunity of re-seeing the West from a Native perspective – something long overdue.

All photographs courtesy of H. Malcolm Grimmer, Santa Fe.

The author would like to express his gratitude to Tom Cleary for his invaluable help with this article.

To view an online database of archived ledger books go to https://plainsledgerart.org/

To read the full text of Tom Cleary’s article “The Macnider Ledger Book: Coloring the Plains” go to www.metroshownyc.com/essays-1/the_macnider_ledger_book

A bibliography on ledger art suggested by Tom Cleary:

Berlo, Janet. Plains Indian Drawings, 1865-1935: Pages from a Visual History. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1996.

Maurer, Evan M. Visions of the People: A Pictorial History of Plains Indian Life. Minneapolis, MN: The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1992.

Calloway, Colin. Ledger Narratives: The Plains Indian Drawings of the Lansburgh Collection at Darmouth College. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

Afton, Jean et al. Cheyenne Dog Soldiers: A Ledgerbook History of Coups and Combat. Niwot, CO: University of Colorado Press, 1997.

Bates, Craig et al. The Cheyenne/Arapaho Ledger Book: from the Pamplin Collection. Portland, OR: Dr. Robert Pamplin Jr., 2003.