Collector's Corner

WONDERS IN STONE: Collecting Inuit Sculpture

Since the earliest times, the Inuit have created sculptures. However, being a nomadic people, these works were small so that they could easily be transported. The Contemporary Period of Inuit sculpture is said to have begun in 1949, when John Huston introduced this art form to collectors in southern Canada and the world beyond. The sculptures were sold through The Canadian Handicrafts Guild in Montreal, and by the 1950s and 60s, Inuit-owned and operated co-operatives had also been established in Arctic communities. Inuit sculpture attracted international interest, but there was an insufficient amount of walrus, narwhal, and whale ivory, the traditional carving medium. Instead, soapstone was obtained from local quarries as well as imported from Brazil. However, contrary to what many believe, most Inuit carvings are not made from this type of stone. Many artists choose to work with harder stone such as peridotite and serpentine.

Although most Inuit art is representational, a number of artists, including sculptors, produce minimalist, abstract, and surreal works. As a collector, I have been attracted to all of these artistic forms of expression as well as works that are controversial.

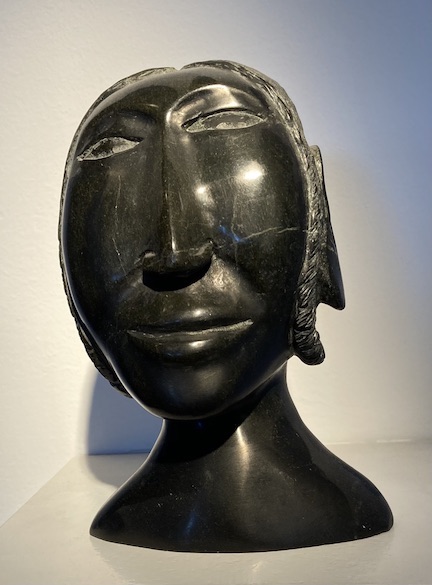

For the most part, because of space considerations, I have collected Inuit works on paper rather than sculpture, though early on in the 1990s, I did acquire a number of Inuit sculptures. Among my favorite pieces are Bear and Walrus by Charles Inukpuk, Figures by Lucy Tasseor Tutsweetok, Torso by Oviloo Tunnillie, Mother Superior by David Ruben Piqtoukun, a portrait bust titled Inuit Woman by Kelly Pishuktee, and Transformation Spirit by Eli Salualuk. At the time, I knew almost nothing about Inuit art and acquired work based simply on intuition, something I still do for the most part.

|

|

| Bear and Walrus by Charles Inukpuk, Inuit, Inukjuak, soapstone, 7” x 5” x 3¾” (1998.). Collection of E. J. Guarino | Figures by Lucy Tasseor Tutsweetok, Arviat (1995). Collection of E. J. Guarino |

|

|

| Torso by Oviloo Tunnillie, Inuit, Cape Dorsetm serpentine, 7”h and 4”w at the base (2003). Collection of E. J. Guarino |

Mother Superior by David Ruben Piqtoukun, Paulatuk, N.W.T., 10” tall (1997). Collection of E. J. Guarino |

|

|

| Inuit Woman, bust by Kelly Pishuktee, Igaluit, Nunavut, 7” tall (1992). Collection of E. J. Guarino | Transformation Spirit by Eli Salualuk, Soapstone, Povungnituk, N.W.T., 9” tall (ca. 1982). Collection of E. J. Guarino |

Perhaps because the archival boxes in which I keep works on paper are becoming full, I recently decided to revisit the collecting area of Inuit sculpture. I hadn’t looked at or considered adding Inuit sculpture to my collection in many years. I simply felt that I had no space for it. However, I was still collecting Native American pottery and finally realized that if I could find space for pottery, which is generally larger, I could find space for Inuit sculpture.

Autoerotic Asphyxia by Pitseolak Qimirpik, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Sculpture in stone, antler, artificial sinew, 8” x 6” x 2” (2021). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Autoerotic Asphyxia by Pitseolak Qimirpik, which I acquired in 2023, is the first Inuit sculpture that I added to the collection in almost thirty years, and it is truly extraordinary – in common parlance, a doozie. It is not to everyone’s taste and is somewhat shocking as it deals with a sexual fetish. Some seeing this sculpture might be a bit perplexed. It is not terribly difficult to figure out what the figure is doing, but the question becomes why? Erotic asphyxiation, whether practiced solo or with another person, is not part of the average person’s sexual repertoire. However, this sexual activity has been practiced in many cultures over time. It is employed in the belief that the intentional restriction of oxygen to the brain heightens arousal and pleasure. One should not assume, however, that because Pitseolak Qimirpik created this piece that he practices this fetish. Despite the fact that he lives in the Arctic, the wider world is available to him via TV, movies, and, perhaps more importantly, the Internet. In terms of proclivities one can Google anything on the sexual spectrum from vanilla to heavy duty kink. It is also possible that the artist knew of someone who died as a result of autoerotic asphyxiation, which is often a result of this practice.

Clumsy Hunter by Andrew Palongayak, Inuit, Uqsuqtuuq, (Gjoa Haven), Stone, antler, 7” x 7” x 4” (2013). Collection of E. J. Guarino

I was first attracted to Clumsy Hunter by Andrew Palongayak because of the mottled stone that the artist used. However, the more I looked at the piece the more I realized that, rather than being deadly serious, the piece was more likely intended to be darkly humorous. The hunter, who is being tossed over the back of a musk ox, has clearly made a miscalculation. Muskoxen are massive animals, and a clumsy hunter would definitely be at a disadvantage. Muskox wool, called quviut in Inuktitut, is highly valued for its softness, length,h and insulating qualities. The Inuit hunt the muskox, called umingmak in Inuktitut, under a quota system with the Canadian government setting harvest numbers to protect the species. Not every musk ox hunt is successful and Clumsy Hunter may refer to one that had a less than desirable outcome.

Two Figures by John Pangnark, Inuit, Arviat, stone, 5” x 3″ x 3 1/2” (circa 1960s). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Although representational art appeals to me, I find that, more and more, I am frequently drawn to work that is minimalist and abstract. I tend to gravitate to the work of artists who are willing to take risks, experimenting with unique and even radical forms that might not immediately be embraced. Two Figures by John Pangnark certainly meets that criteria. The sculpture presents two individuals in close proximity, who are rendered in a minimalist fashion. Who the figures represent is left up to the interpretation of each viewer. The sculpture may portray a parent and child, two lovers, or two friends. Even the sex of the figures is left up to each person to decide. It is a fascinating way for the artist to engage his audience in an unexpected way.

Over time, Pangnark’s artistic aesthetic shifted from realism to abstraction, with the forms he created being less defined and his figures no longer having limbs. The human form almost exclusively became the focus of the artist’s work with radically simplified shapes and minimally worked stone so that figures sometimes were reduced to what simply appears to be a rock. Pangnark’s non-representational style is at once enigmatic and powerful. His sculptures are as much about medium, form, line, and mass as it is about the subject matter. John Pangnark’s sculptures offer a sharp contrast to that of much contemporary Inuit sculpture, which tends to be representational and naturalistic. Inuit art scholar George Swinton referred to Pangnark as the “Brancusi of the North.”

Animal by Andy Miki, Inuit, Arviat, stone, 5” x 4 1/4” x 2” (1975). Collection of E. J. Guarino

As with Two Figures by John Pangnark, Animal by Andy Miki is equally minimalist, abstract, and ambiguous. The piece may depict a bird, a dog, or neither one of those creatures. As a collector, I found the roughness and ambiguity of the piece intriguing.

While other sculptors from the Arctic community of Arviat were depicting the human form in minimalist and abstract ways, Andy Miki carved out a niche of his own. He focused on creating minimalist, small-scale works that depicted animals. Rather than concentrating on the torso and limbs of his pieces, Miki focused on the head. The creatures he produced – usually birds, dogs, caribou, and bears – were often recognizable by their nose. However, much of Miki’s work is intentionally ambiguous. The artist’s inspiration came from personal observations of Arctic wildlife as well as his imagination.

Carvers from Arviat use soapstone, also known as steatite, which is extremely hard, making it difficult to carve and polish. Often in such works, the marks of the sculptor’s tools can be seen on finished pieces as in Miki’s Figure. There are those who believe that the demanding labor required to sculpt soapstone contributes to the rough-textured sculptures produced by carvers from the Arviat region.

After so many years of not acquiring Inuit sculpture, I am finding it extremely interesting to add to this portion of my collection once again. In addition to collecting the work of well-established sculptors, it has been exciting to learn about the work of emerging artists. As with all of my collecting, it is an ongoing journey.