Collector's Corner

I DID IT MY WAY: The Unapologetic Art of Sheojuk Etidlooie

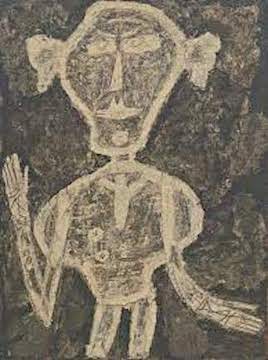

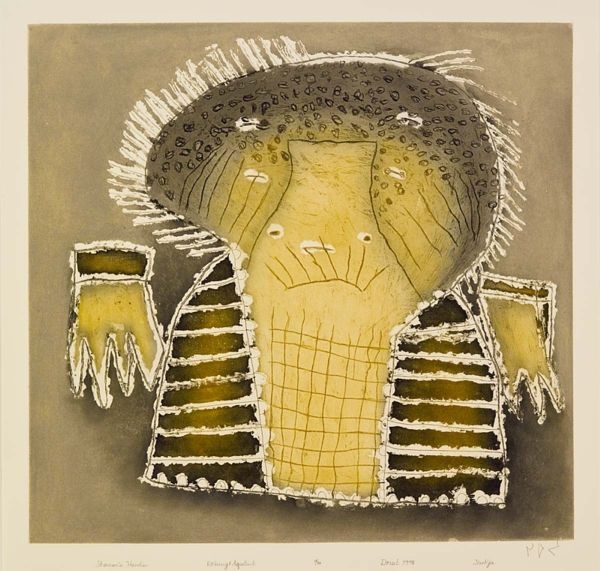

As I was standing in front of Jean Dubuffet’s painting Portrait of Henri Michaux, on a recent visit to the Museum of Modern Art, I was immediately struck by the notion that it had a familiar quality, but I couldn’t quite determine what it was. Not long after, I had a eureka moment. (Well, anyway, I thought it was). There was something in Dubuffet’s painting that reminded me of some of Inuit artist Sheojuk Etidlooie’s works. I’m sure that neither artist influenced the other, nor had they even heard of one another, but it seemed to me that there was an aesthetic affinity between their work. In particular, Dubuffet’s Portrait of Henri Michaux and Etidlooie’s Shaman’s Hands has a number of artistic qualities in common.

Sheojuk (as gallerists, collectors, and curators usually refer to her) had a dynamic artistic sense; she did not allow her vision to be swayed by accepted conventions and did not allow others to dictate what her drawings and prints should be. Through her bold style, she created a visual language unlike that of any of her contemporaries. To some, Sheojuk’s imagery might appear to be childlike or naïve, but they are the result of a mature artist grappling with specific artistic problems. Sheojuk’s art exemplified a straightforwardness and appearance of spontaneity that many European artists, Dubuffet among them, worked to achieved. Often, artists wrestling with the same artistic concerns come up with similar solutions. Perhaps this phenomenon could be termed Convergent Creativity, or Parallel Inspiration since it results in analogous outcomes.

Portrait of Henri Michaux by Jean Dubuffet, French, oil on putty, pebbles, and sand on canvas, 51 1/2” x 38 3/8” (1947). Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Dubuffet’s work is informed by naïve art and graffiti, which he termed Art Brut, or “raw art”. As an artist, he was reacting against art produced by academically trained artists, which he considered stultifying. He wished to create art that was raw, not filtered through ideas of what people thought art should be. He turned for inspiration to the work produced by children, prisoners, the insane, and self-taught artists. Dubuffet challenged the concept of what constitutes fine art.

Shaman’s Hands by Sheojuk Etidlooie, Inuit, Cape Dorset, etching & aquatint, 32” x 31 1/4” (1998). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Sheojuk’s Shaman’s Hands is a remarkable work. The shaman depicted is a strange being, delineated with odd marks. He doesn’t seem quite human. Is he in the midst of transforming into or back from being an animal? The work’s title indicates the importance of the shaman’s hands, but we do not know why. They look claw-like and one of them does not appear to be attached to the shaman’s body. His head is covered with bristly hair that could be fur and, rather than having two eyes, the shaman appears to have four or, even, six. His face seems snout-like and it looks as if he is bursting out of his clothing or skin. With the use of just three colors – brown, gold, and off-white – Sheojuk managed to create a mysterious, almost mystical work and the techniques of etching & aquatint add a visual impression of texture to the print as well.

Although her artistic career lasted only seven years, Sheojuk Etidlooie was a singular voice among Inuit artists. In her brief career, she produced some 460 drawings and forty-four prints. Sheojuk had a distinctive style (some might use the word eccentric to describe it), which is not comparable to that of any other Inuit artist. The colors she employed seem to glow and she ignored the conventional rules of representation and, instead, depicted her world in her own unique way, preferring minimalism and abstraction to realistic depictions. In a sense, her work can be said to be “raw” since she did not allow accepted practices to stand in the way of her artistic vision.

In spite of the fact that Sheojuk Etidlooie did not create her first drawing until she was in her mid-sixties, she left behind an impressive, highly personal body of work.

Born in 1929 at an outpost camp not far from Kinngait (Cape Dorset), like most Inuit at the time, Sheojuk’s family led a nomadic life, which was governed by the availability of food. These early experiences later informed Sheojuk’s art, though in a most unusual way.

When she married, Sheojuk and her husband moved to Ikpiarjuk (Arctic Bay), then to Iqaluit, and in the 1990s she returned to Kinngait. Sheojuk’s artistic career begin in an unusual way in 1993: At the church Christmas games, she made a drawing of a quilliq (a seal oil lamp), which won first prize. This was particularly meaningful since it was awarded by Kananginak Pootoogook and Paulassie Pootoogook, two of the most highly respected artists in Kinngait.

Sheojuk Etidlooie had great admiration for the other Kinngait artists, many of whom had gained national and international fame. She worked diligently on her art, producing drawing after drawing. In an interview with Pat Feheley, owner of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, in July 1998, Sheojuk stated, “I started out drawing by accident . . . and ever since then I have gained confidence. I have to think about a drawing for a while before I start to make it. My drawings are from me, they are my own but it is not easy to make them.”

The other artists at the Kinngait Studios did not understand Sheojuk Etidlooie’s vision; her minimalist and abstract drawings often elicited whispers and sniggers. However, this did not deter Sheojuk. She simply went to another room and worked in private, producing multiple drawings each day. In 1994, her drawings were made into prints for the first time and from that year on she was represented in every Cape Dorset spring and fall graphics collection until 1999, the year of her death.

Although Sheojuk Etidlooie explored themes common in Inuit Art, she did so in a style that was highly personal. Her drawings and prints of humans, birds, fish, bears, and other Arctic creatures are unlike anything produced by her contemporaries. What Sheojuk created was often blob-like and ambiguous, which is what makes her work so fascinating. Unlike other Kinngait artists of the period, she was not interested in documentation. Her work evokes an emotional response from the viewer, if nothing other than a curiosity about what exactly it is that they are looking at.

Nurraq (Young Caribou) by Sheojuk Etidlooie, 1/50, lithograph, Cape Dorset, #22, 22 1/2” x 30” (1998). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

In her print, Nurraq (Young Caribou), Sheojuk did not belabor her depiction of the animal. She was not interested in producing an exact replica; photo realism was not her artistic concern. Instead, with an economy of line, she created an image that captures the essence of a caribou and is easily identifiable to the viewer. The animal’s body resembles that of a child’s plush toy while its spindly legs end in triangular shaped hooves. Attached to the caribou, by what appear to be strings, are two balloon-like objects that appear to be floating above it. It is anyone’s guess as to what they are, though they may very well represent ears. Such a creature could only come from the mind of Sheojuk Etidlooie.

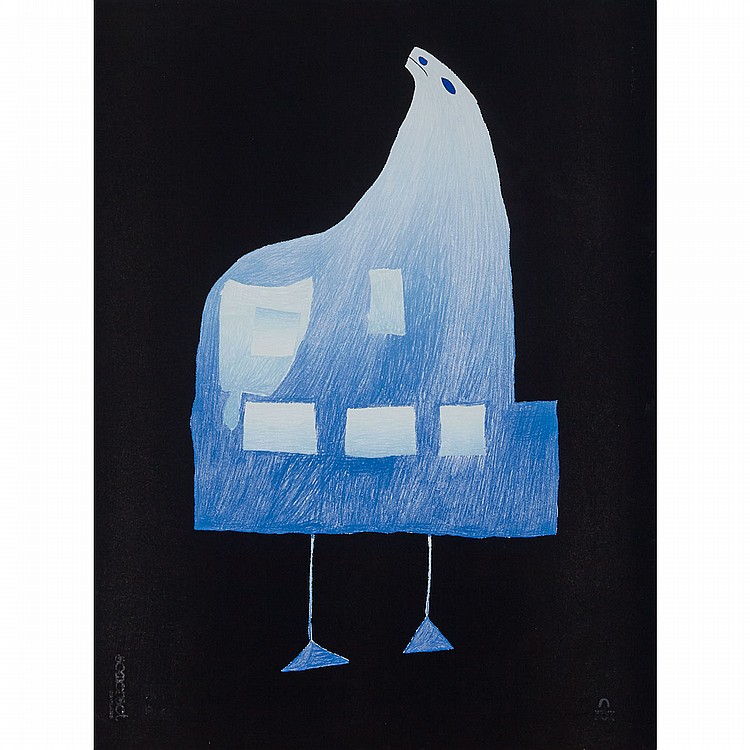

Bird in Winter Night by Sheojuk Etidlooie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), lithograph, ed. 50, #29 Annual Cape Dorset Print Collection, Printmaker: Pitseolak Niviaqsi R.C.A., 30” x 22.25” (1999). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Looking very much like a blue piano that has been turned on end, Sheojuk Etidlooie’s Bird in Winter Night is a strange, but amusing work. The artist has pared down her portrayal of a bird and the darkness of an Arctic winter night to the bare essentials. Sheojuk centered the subject of her print on the page (a common practice among Kinngait artists), but any resemblance to the work of her contemporaries ends there. The background is a stark black. The bird itself is minimalist in its presentation and, although the viewer is most probably unable to identify to which species the bird belongs, the generic word bird is used in the title, perhaps indicating that the kind of bird depicted is irrelevant. As with her portrayals of other animals, Sheojuk gave her bird triangular feet. It is rendered in shades of blue with lighter hues representing feathers, which are simply suggested. Sheojuk’s print certainly gives the viewer a great deal to ponder.

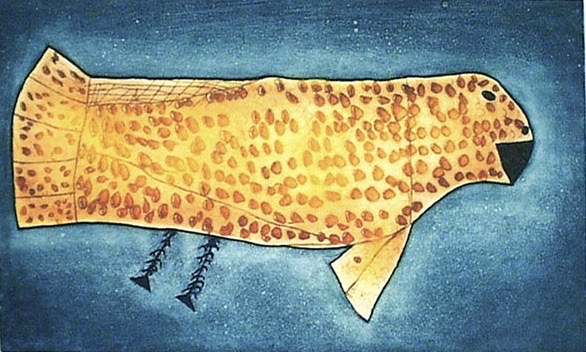

Puigi(Sea Beast) by Sheojuk Etidlooie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), etching & aquatint, 26 3/4” x 39 1/4” (1999). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Puigi (Sea Beast), also translated as Creature from the Sea, is yet another curious Sheojuk work. Once again, the artist has used a triangular shape to indicate the creature’s feet. However, stranger still are the its legs. At one and the same time, they look like metallic rods with protrusions as well as plantlike stems with shoots. The sea beast itself looks very much like one of Sheojuk’s birds and could easily be mistaken for one. As befitting such an underwater setting, the background is in shades of blue with the lighter areas outlining the sea beast and becoming darker in the outer areas of the page. The creature itself is presented in bright yellow with a dark black mouth and one black eye showing. Scales are suggested by splotches of gold. Once again, Sheojuak produced a fascinating and mysterious image with an astonishing economy of line.

Searching Bird by Sheojuk Etidlooie, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), lithograph 22 1/2” x 30 (1998). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto

Some of Sheojuk’s most unusual images are of birds and her print Searching Bird is no exception. The subject of the print is delineated in a simple, straightforward manner. Once again, the artist doesn’t seem to be particularly interested in depicting a specific type of bird, but in exploring the very nature of this type of animal. Sheojuk employed just three colors: yellow, which dominates the print; green; and shades of brown. The green lines on the brown background appear to bleed through onto the yellow of the bird, giving the print an enigmatic quality. The bright yellow bird is one of the artists blob-like creations and, as such, is somewhat humorous, resembling a bird you might encounter in a cartoon. Sheojuk indicates that the bird is searching (for what we don’t know) by simply having its head pointed upward. Once again, the viewer is drawn into the artist’s unusual perspective on her world.

Although Sheojuk Etidlooie came late to art making, she took her work seriously, never allowing others to impose their ideas on her. In spite of the fact that her work is treasured by many collectors, she has not achieved the legendary status of some other Kinngait artists who were her contemporaries. In many ways, Etidlooie’s art was avant-garde and, in terms of what was being produced by other Inuit artists of the period, it was revolutionary. Many, including collectors, curators, and fellow artists of the time, did not “get” what Etidlooie was doing. Over time, more and more people have come to understand and appreciate Etidlooie’s accomplishments. Sheojuk Etidlooie’s work is not as well known as that of many of her contemporaries, but it deserves to be.