Collector's Corner

UKIYO-E: The Influence of the Floating World on Rick Bartow’s Prints

Discovering what inspired an artist to create a particular work or why he or she used a particular style is always fascinating. In the case of Rick Bartow the influences are many and intriguing: his Wiyot heritage, Vermeer, Klimt, Chagall, Max Beckmann, Francis Bacon, Odilon Redon, Horst Janssen, Edward Hopper, Hieronymus Bosch, Expressionism, and Surrealism. In addition, more than a few pieces contain literary or musical allusions. As a collector, I recently focused on one influence in particular: Japanese prints.

Referred to as Ukiyo-e, this genre of woodblock printmaking was particularly popular in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868). During this time, Edo, what is modern-day Tokyo, was the capital of Japan. The merchant class, which profited from the city’s rapid growth, was able to indulge in pastimes that their new-found wealth afforded them – the kabuki theater, courtesans, and geishas. Ukiyo-e illustrated scenes from the “floating world.” Uki translates as floating, yo as world, and e as picture.

Ukiyo-e presented subjects such as female beauties; wakashu, beautiful male youths considered a “third gender,” which occupied a distinct position in during the Edo period; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; illustrations of Japanese classic literary works such as The Tale of Genji; travel scenes and landscapes; fauna and flora; and erotica known as shunga. Originally a Buddhist term meant to convey the concept that earthly life is ephemeral, ukiyo-e became associated with the fleeting diversions of Edo’s licensed pleasure districts and the theater.

Ukiyo-e was a collaborative art form. Artists rarely created their own woodblocks. Instead, they worked closely with a carver, who cut the images into wood; a printer, who inked and pressed the woodblocks onto paper; and a publisher, who distributed and promoted the artist’s work. Like his Ukiyo-e counterparts, Rick Bartow worked with Japanese printers, papermakers, as well as gallerists who exhibited and promoted his work: master papermaker Naoaki Sakamoto, master printer and gallery owner Seiichi (Seii) Hiroshima, and gallery owner Toshiaki Yanagisawa.

As with Manet, Degas, Monet, Van Gogh, and Toulouse-Lautrec before him, Japanese prints made a strong impression on Rick Bartow. Many of his prints show the influence of ukiy-o, some in obvious ways, others subtly. In some of Bartow’s Japanese inspired prints, such as Eros, Hypnotist, and Otsu-e, the references are apparent. In Bertolt Brecht (3 Penny Opera), the effect is understated while in both versions of Nach Hopper the connection is suggested by line or color choice.

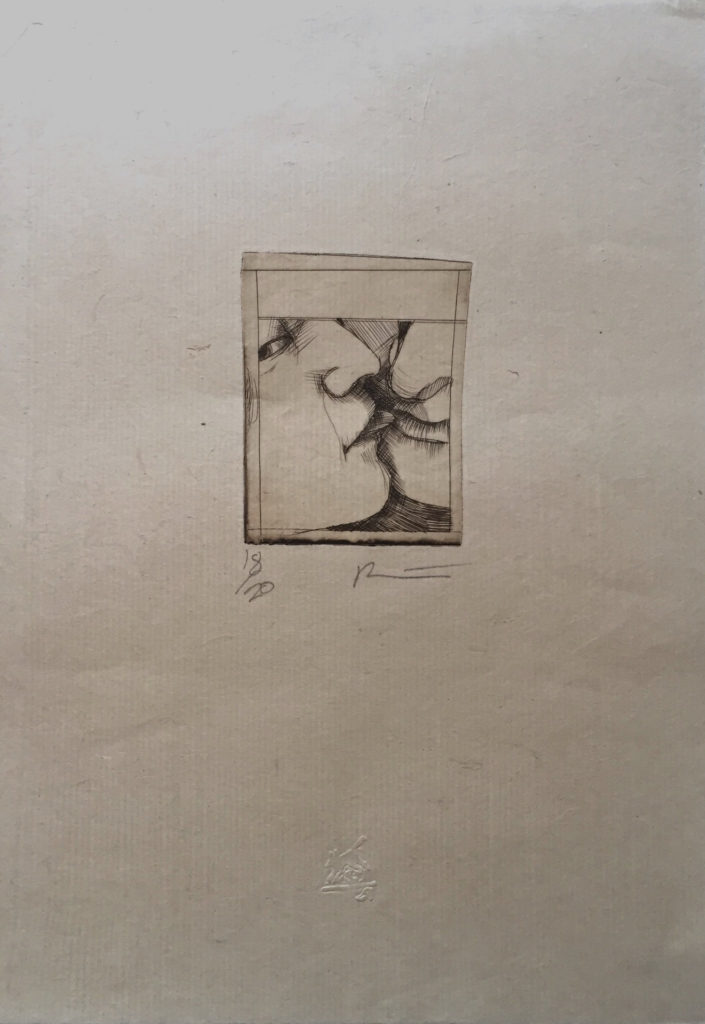

Eros by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, ed. 18/20, 4” x 3” (2000).

Collection of E. J. Guarino

Eros (detail)

Rick Bartow did something quite interesting with regard to his creation of Eros, a work that draws heavily on the traditions of shunga prints. Erotic works in this type of Ukiyo-e are quite explicit, showing partners performing various sexual acts with the genitalia of the male often greatly exaggerated. Bartow, however, takes a different approach that amounts to the difference between a long shot and a close up in cinema. The focus of Eros is not on the bodies of the participants, but on their faces. The sexual nature of the couple’s encounter is evoked through a simple gesture – the extension of the female’s tongue towards the male’s lips. The choice not to use color is another difference between the Bartow print and shunga works. Instead, Eros consists of black lines on off-white paper, adding to the piece’s muted eroticism.

There are also other intriguing aspects to the print. The female’s eye seems to be giving a side glance, suggesting she is looking at the viewer rather than her paramour. This detail draws any observer into the sexually charged atmosphere of the work. The depiction of the male figure is even more curious. Little of his face can be seen and what is apparent resembles the artist’s own features, intimating that this print may portray some sexual encounter Bartow experienced during the Viet Nam War. Also, despite the print’s Japanese allusions, it’s title references Greek mythology since Eros was the god of sexual love. In English, the deity’s name is a term for physical love, giving us such words as erotic and eroticism. As an artist, Rick Bartow packs a great deal of meaning into even his small prints. Their size belies their importance.

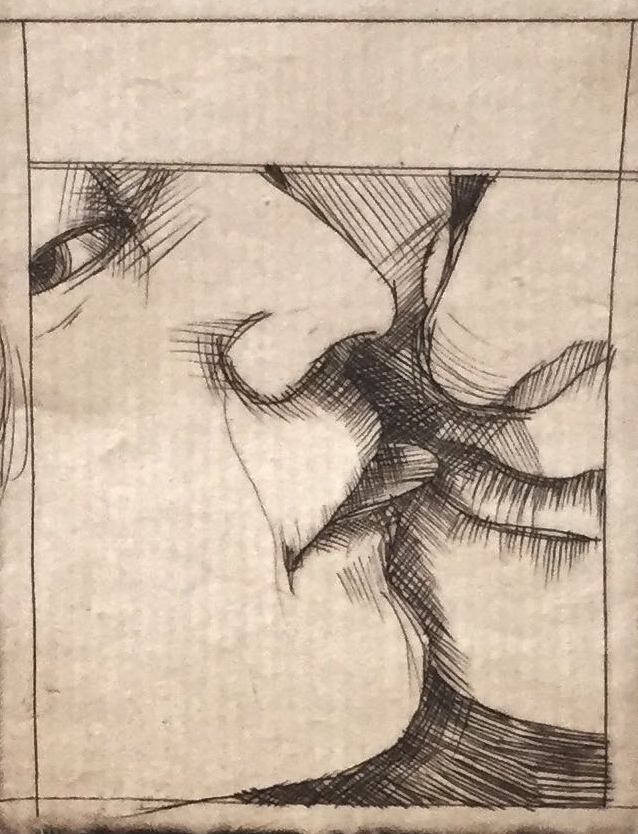

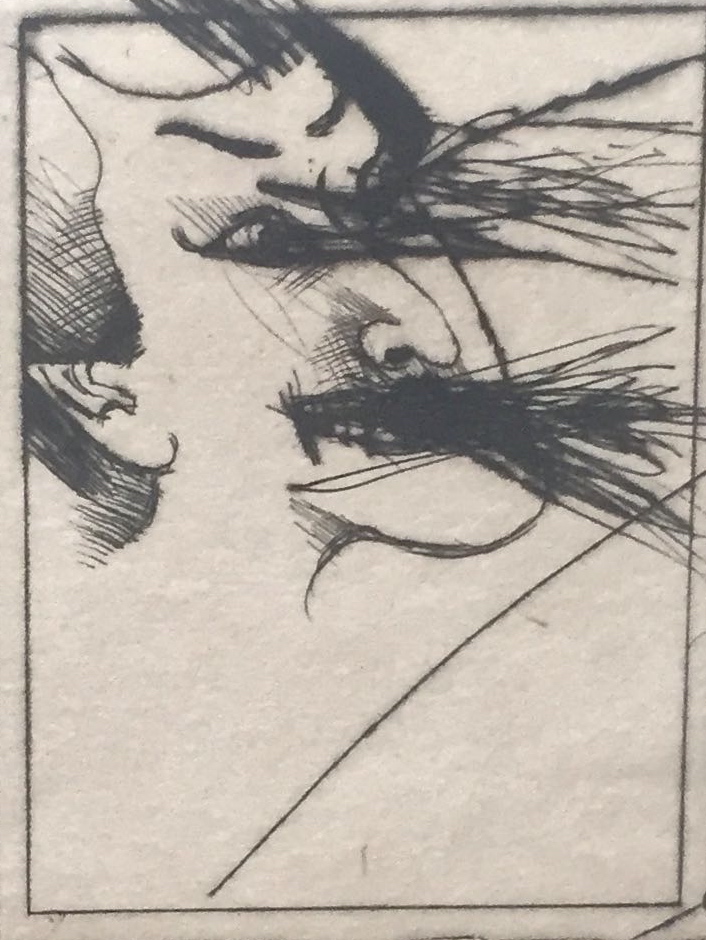

Hypnotist by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching on Japanese paper, ed. 6/10, 4” x 3” (1998). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Hypnotist (detail)

Hypnotist, like Eros, has a decidedly ukiyo-e quality yet, at the same time, the execution is quite modern. Once again, the artist has chosen to employ black lines on an off-white page rather than the bold colors one might expect in a work inspired by Japanese prints. Graphic artists, much like movie directors, focus the viewer’s attention. What they don’t want their audience to see is as important as what they do want them to see. As in Eros, Rick Bartow has chosen to employ what is, essentially, a close-up. Rather than seeing the hypnotist’s full body and clothing and the setting in which this character might exist, we are directed to look solely at the face. The figure is clearly Japanese and drawn very much like one might expect to see in a traditional ukiyo-e print. However, Bartow has added an element that is artistically shocking and quite contemporary: the addition of scratch marks across the hypnotist’s eyes and mouth. At first one might assume that the artist was, in essence, trying to cross out his creation. However, mark making was extremely significant to Rick Bartow and it is important to see how the lines were drawn. These streaks appear to be radiating outward from the figure’s face, symbolically suggesting the hypnotist’s power.

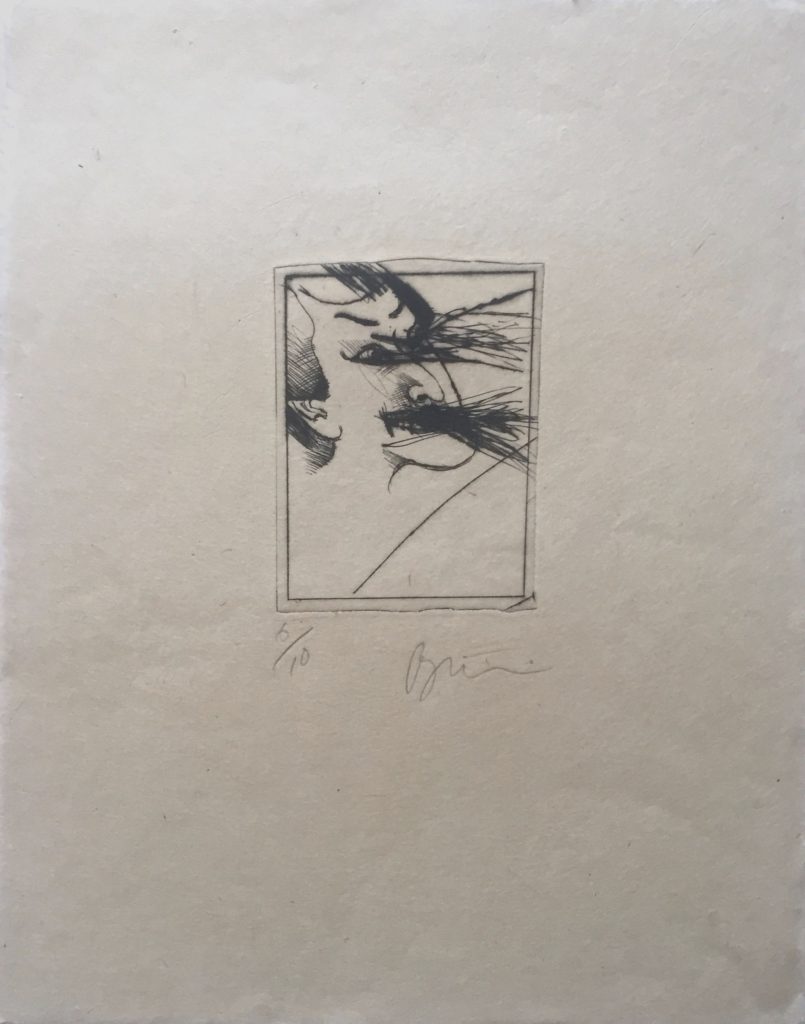

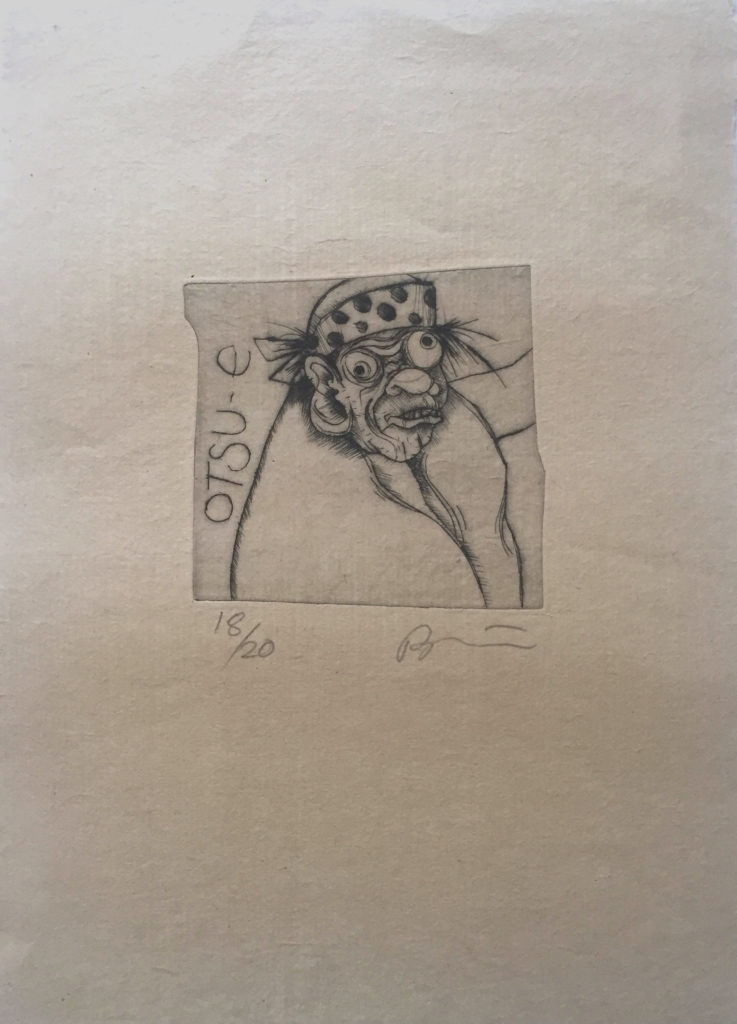

Otsu-e by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, ed. 18/20, 4” x 4” (1999).

Collection of E. J. Guarino

Otsu-e (Detail)

When I first saw Otsu-e I didn’t quite know what to make of it except that I liked it. Looking very much like a traditional ukiyo-e print, this Rick Bartow work struck me as humorous and a bit scary. I had no idea what the word Otsu-e meant, but thought that it might be the name of the figure that was portrayed. In doing some research, I discovered that I was wrong. Otsu-e, meaning pictures from the town of Otsu, became a sort of cottage industry in 17th century Japan. Located on the Tokaido Road, which connected Edo and Kyoto, the town of Otsu was a port on Lake Biwa and a crossroad for trade. During the 1600s this route allowed merchants and other travelers access to the most important cities of the time: Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka. Taking advantage of the busy foot traffic, local people developed a type of folk art similar to ukiyo-e, but less artistic. Sometimes entire families collaborated in producing otsu-e. These unsophisticated prints could be produced quickly and inexpensively and were sold to passersby as souvenirs from stands set up along the road. Created by anonymous artists on rough, tan-colored paper, the prints depicted Buddhist themes, demons, deities, courtesans, legendary warriors, and popular folk characters and were often satirical in nature. The features of many of the characters portrayed, especially the demons, gods, and warriors, were frequently exaggerated.

In his version of otsu-e, Rick Bartow creates a character with a heavily wrinkled face, bulging eyes, and outsized nose and ears. Whether the artist based this figure on a traditional otsu-e print or it was created solely from his imagination we may never know. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter. The end result is a marvelous work of art that is both fun and intriguing.

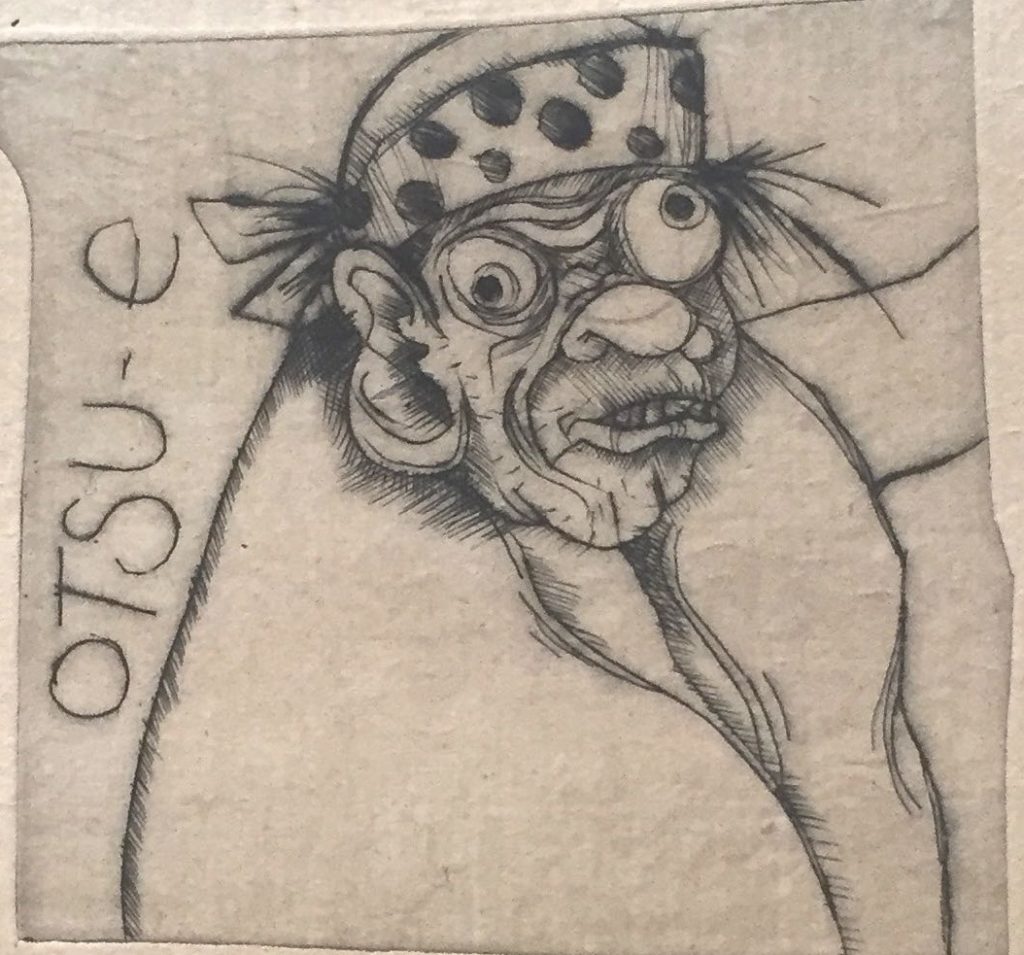

Bertolt Brecht/3 Penny Opera/Dri Groshen Oper by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, hand colored drypoint etching, ed. PP/, 7” x 5.5” (1999). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Bertolt Brecht/3 Penny Opera/Dri Groshen Oper combines elements of ukiyo-e, otsu-e, and film. The print’s title not only references Bertolt Brecht, but what is, perhaps, the playwright’s most famous work: The Threepenny Opera. Based on John Gay’s 18th-century ballad opera, The Beggar’s Opera, the play’s text was written by Brecht and Elizabeth Hauptmann, though Brecht took sole credit, and the music by Kurt Weill. Although at the time it was produced The Threepenny Opera was considered a play with music rather than a musical, it nonetheless had and continues to have, a worldwide influence on the musical as a theatrical genre.

The strong colors of Bartow Bertolt Brecht/3 Penny Opera/Dri Groshen Oper are reminiscent of ukiyo-e prints and the theatrical posters of Toulouse-Lautrec who was also influenced by Japanese prints. The characters portrayed are rendered in such a way that they suggest the multiple exposures possible with film. While a man with eyeglasses and a large nose, and hand to head stares downward in concentration, characters swirl around him, suggesting that they are creations of his imagination. The print is actually a portrait of Bertolt Brecht in the process of creating the characters for The Threepenny Opera.

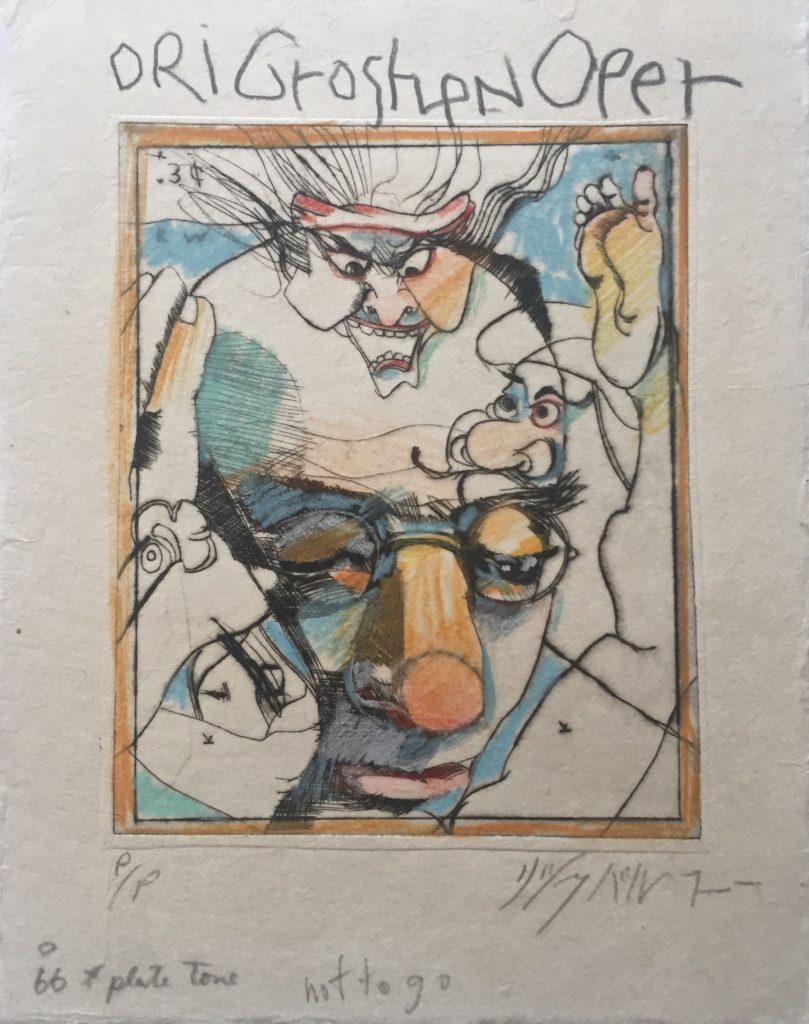

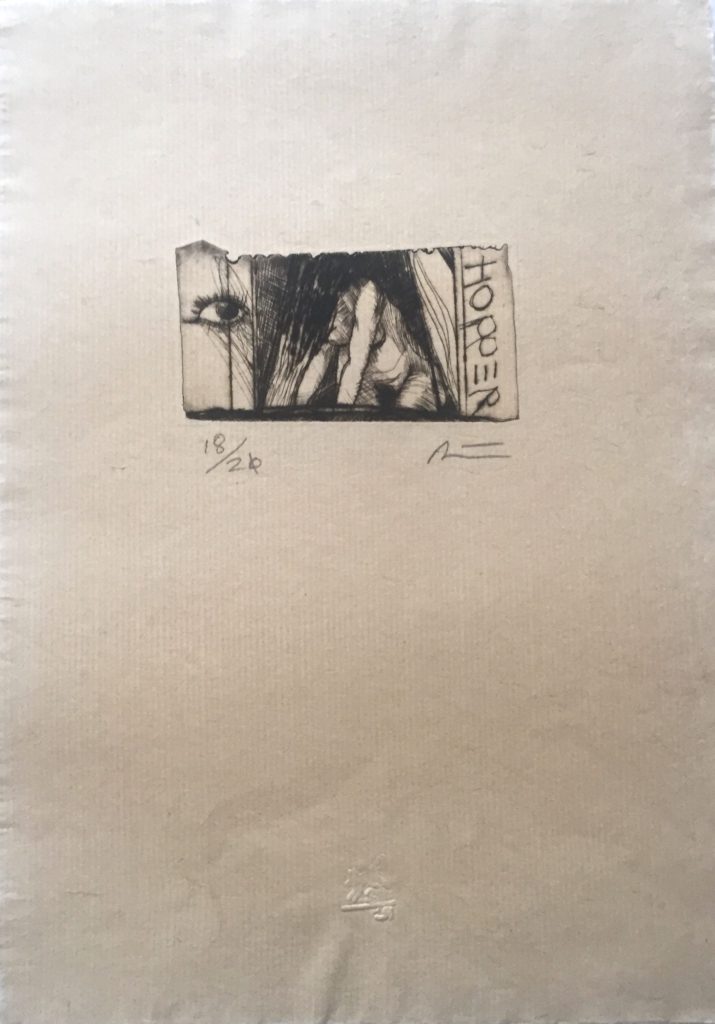

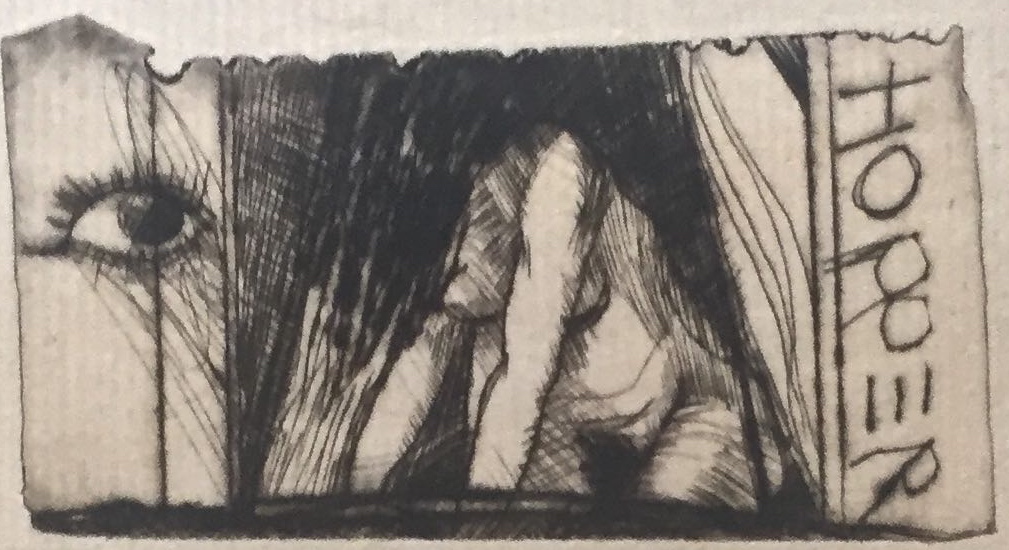

Nach Hopper by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, ed. 18/20, 2” x 4” (2001).

Collection of E. J. Guarino

Nach Hopper (Detail)

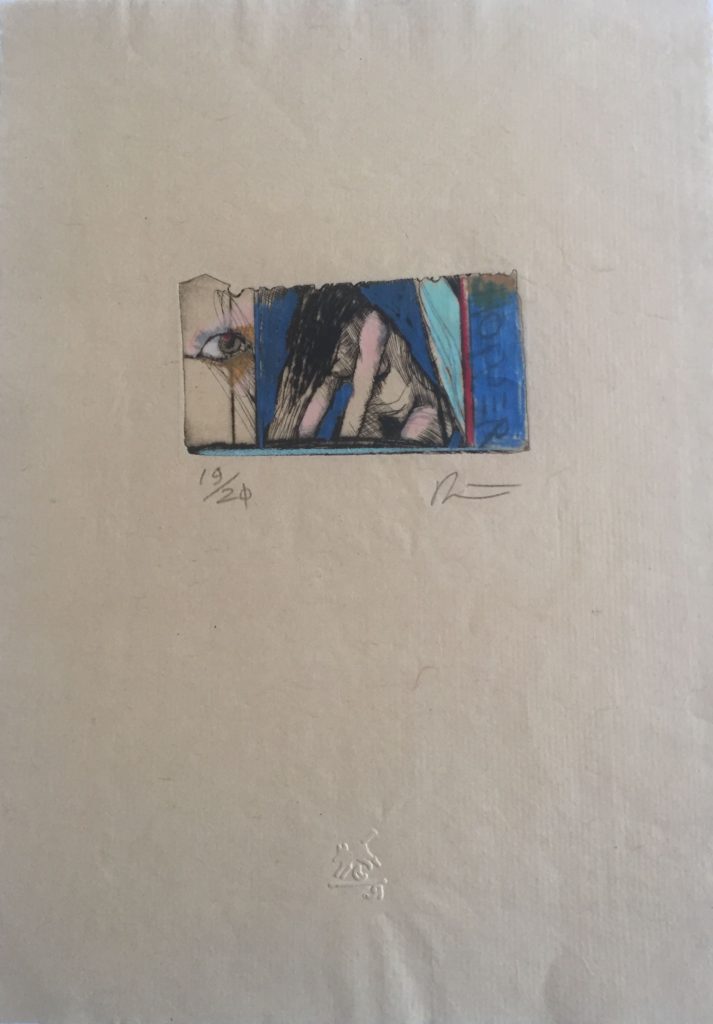

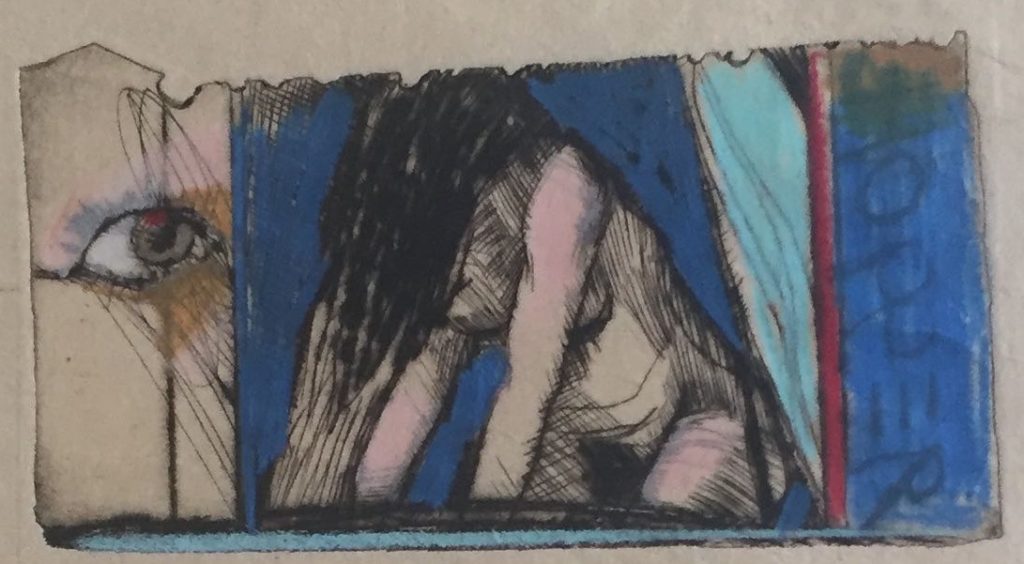

Nach Hopper by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, hand colored drypoint etching, ed. 19/20, 2” x 4” (2001).

Collection of E. J. Guarino

Nach Hopper, hand colored version (Detail)

Edward Hopper (1882 – 1967) was among the many artists who influenced the work of Rick Bartow. Mostly known as a painter, Hopper was also a printmaker who created etchings, which reflected his insight into life as it was lived in modern America. His prints had a gritty quality, not unlike etchings created by Rick Bartow.

At first glance, Nach Hopper appears to have little if any influence from the ukiyo-e tradition. Nonetheless, it is there, particularly in the second version of the print. Nach Hopper (translated from German to mean After Hopper) reflects the realistic urban scenes Hopper favored in his etchings. In works such as The Lonely House, Night in the Park, East Side Interior, and The Locomotive Hopper presents an uncompromising vision of city life – lonely, isolated and, in prints such as Night on the El Train, a suggestion of a furtive sexuality. In Nach Hopper all of these elements are evident – the nude woman whose face is obscured is flanked by a disembodied eye – a symbolic Bartow trademark whose interpretation is left up to the viewer. Yet, despite the homage to Hopper, Bartow’s print displays aspects of ukiyo-e – delicacy of line, a sense of texture, and a contrast between light and shadow.

The influence of ukiyo-e is more apparent in the hand colored version of Nach Hopper produced in the final months of the artist’s life. Bartow’s color choices – blue, pink, turquoise, red – heighten the realism of the piece and also indicate the artist’s familiarity with the color palette of traditional Japanese prints.

As a collector, I have been particularly interested in Rick Bartow’s drypoint etchings. Drypoint is a technique in which the artist uses a sharp metal or diamond point, referred to as a “needle,” to incise an image directly onto the printing plate. As with drawing, the viewer senses the hand of the artist, but perhaps more so since with drypoint there is no possibility of erasures. The work comes directly from the mind of the artist to the hand and onto the plate. To produce his drypoint prints, Rick Bartow worked closely with Seiichi (Seii) Hiroshima, who owned a gallery in Tokyo and who hosted several exhibits of Bartow’s work. According to Charles Froelick, “Hiroshima is the printmaker (master printer) who editioned Rick’s drypoints. . . . Rick and Seii call their collaborative press ‘Moon and Dog Press.’ Their chop is found on nearly all of the prints they made together – a dog jumping over a moon and a backwards ‘R’.”

For me, there is something deeply personal about Rick Bartow’s drypoints, a sense of immediacy, which I find compelling and impossible to resist since the artist could not make corrections or changes as was possible with his drawings and paintings. I find the intersection of Bartow’s esthetic and Japanese ukiyo-e prints particularly compelling. This aspect of the artist’s work will continue to influence which prints I acquire and I have been lucky to have had the tutelage of Charles Froelick in this endeavor.

The author would like to express his thanks to Charles Froelick for his help with this article and for his assistance in acquiring so many prints by Rick Bartow.

You might also be interested in:

RICK BARTOW: REMEMBERING AN AMERICAN MASTER