Collector's Corner

ADVENTURES IN COLLECTING: Facing the Challenges of Acquisition

Acquiring art for my collection has been an enjoyable process, except for figuring out how to pay for it. Usually, that has been solved with payment plans. In almost thirty years of collecting I’ve purchased pieces for my collection from shops, galleries, trading posts and directly from artists. Often, art was collected while traveling and, whether returning from Alaska, Canada, Mexico, South America or the Soutwest, I simply carried my acquisitions onto the plane with me. Overall, the process was drama and difficulty free. Times have changed; nowadays I have come to rely more and more on the Internet. Surfing the web has given me access to scores of galleries and artists – all from the comfort of my home. However, the process of collecting has not been without some difficulties. On a few occasions I have had to work very hard to acquire a piece of art by an artist whose work interested me, so much so that the experience became an adventure.

Pitch-coated red-brown vase with fire clouds by Alice Cling, Navajo (Diné), 11”h x 7½”w (c.2002). Collection of E. J. Guarino

While visiting Arizona sometime in 1999, I was discussing the pottery in my collection with Mario Klimiades, the Librarian for the Heard Museum, who asked if I owned any pieces by Alice Cling. I not only had to admit that I did not have any works by this artist but also had to acknowledge that I had never heard of her. Why would I have? Cling is Navajo and, in those days, I concentrated exclusively on collecting the work of Pueblo ceramic artists. Mr. Klimiades spoke so elequently about Cling’s work that I decided on the spot to acquire an important example of her art. That, however, became somewhat of a challenge since, as I traveled throughout Arizona, all I found were small pots by Cling, which I happily purchased since they were so exquisite. On subsequent trips to the Southwest over the next three years, I continued my search. Finally, in 2002 on the last day of a trip, I saw a large and spectacular piece by Alice Cling in the Heard Museum Shop. Although acquiring it put me over my collecting budget (something I try to avoid doing) I knew I should not pass on it. This work remains one of the gems of my collection and was featured in “Forms of Exchange,” a 2006 exhibit at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College.

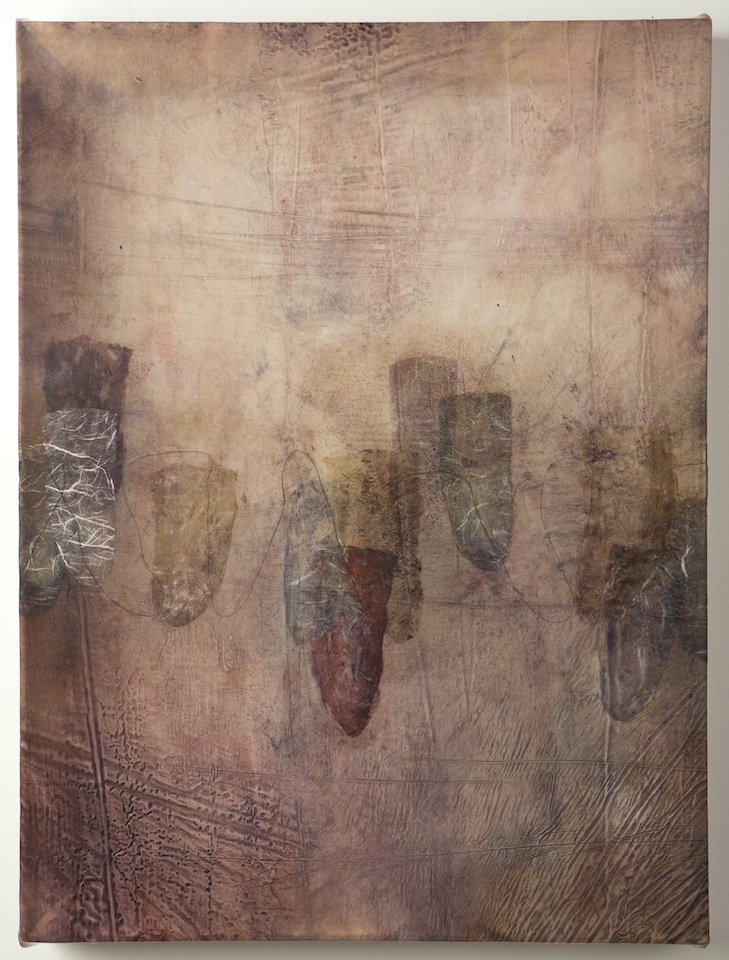

Plum Walrus Family Portrait by Sonya Kelliher-Combs, Inupiaq/Athabascan, acrylic polymer, paper, thread, cellulose, 18” x 24” (2013). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Acquiring the work of Sonya Kelliher-Combs presented a different set of challenges: neither was I able to find the artist’s work in any galleries, nor was I able to connect with her directly. When I first came upon Kelliher-Combs’ work I didn’t quite know what to make of it but I couldn’t get it out of my head (a good sign). In 2010/11, NMAI in New York presented “HIDE: Skin as Material and Metaphor,” which included a large number of works by Sonya Kelliher-Combs. What I saw completely intrigued me. I don’t profess to understand every aspect of Kelliher-Combs’ art (another good sign) but, knowing me, if I did I would lose interest in it. The more I studied the artist’s work, the more determined I became to have examples of it in my collection. I tried contacting the gallery in Anchorage where I had first encountered Kelliher-Combs’ art but it did not have a web site. Over the next few years, I would periodically do Google searches in the hope of making contact with the artist. Finally, in 2013 I met with success. After a series of Email exchanges with the artist I was able to acquire Plum Walrus Family Portrait. We also discussed other pieces I wished to acquire. The connection has been quite fruitfull. Not long after that I came across Kelliher-Combs work at the Zane Bennett Gallery in Santa Fe and acquired a more of her work.

Red Raven, Red Raven by Thomas Greyeyes, screenprint, 13/25, Dine, 19” x 15” (2013). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Of all the artworks in my collection, without doubt, Red Raven, Red Raven by Thomas Greyeyes required the most effort to acquire. Contacting the artist via the Internet was relatively easy and the print was mailed to me on August 15, 2013. That’s when the adventure, of sorts, began. According to the USPS web site the scheduled delivery day was August 21. When that day came and went, I became concerned and went to my local post office where I was told to call the Postal Service’s 800 number or call the post office in Chamisal, New Mexico from where the item had been sent. The 800 number was a waste of time; it only gave me access to an electronic menu with no option to speak to a person. In frustration, I called the post office in Chamisal and spoke to a postal worker who said that she remembered the package and added that, by now, it should have been scanned in Albuquerque. She also told me not to lose hope.

I continued checking the USPS web site on a daily basis and muiltiple times on some days but to no avail. Then, on August 30 the web site indicated that the package had been scanned in Denver. I breathed a sigh of relief. At least the print wasn’t lost. My reassurance was shortlived, however. For two weeks, the print was “stuck” in Denver. Infuriated, I started making phone calls but only reached electronic menus. After more than fifty such calls, I finally made contact with a person who put me in touch with a supervisor. Though he tried, this man was unable to solve the problem and told me to call the USPS Customer Service Representative for the Denver area who assured me that she would personally see to it that my package left Denver. A few days later on September 14, the print showed up on the Postal Service’s web site as being in Kearny, New Jersey. I was overjoyed because it was now only a mere 11 miles away. The package quickly left New Jersey and was in New York by September 16. It won’t be long now, I thought. How wrong I was.

On September 23 the Postal Service’s web site stated, “Arrival at Post Office” so I went to my postal branch expecting to retrieve the print. No one could find it and I was told, “You need to go to the post office on 34th Street.” Armed with all of the information from the USPS web site, off I went. At the 34th Street branch I spoke to a supervisor who looked over the papers I had and said, “Why are you here? Your package wouldn’t come here. And according to this paper you have, it is at the Morgan Sorting Facility.” Then, after a slight pause, he added, “But you can’t go there.” Now I was really irked. Just watch me, I thought.

The Morgan Sorting Facility was only two blocks away and I knew that it was only open to employees. Having nothing to loose, I figured I’d come up with a way of overcoming that obstacle once I got there.

The Morgan Facility had guards and metal detectors reminiscent of airport security. Although I could not enter the building, I knew that my best shot would be to enlist the assistance of someone who could. I explained my situation to a security guard who said he would phone a “higher up” who might be able to help. A few minutes later a gentleman in a suit appeared and, after I once again told my story, he said, “Let me see if I can find the person who can help you.” Within a few more minutes he returned, saying that the Manager of In-Plant Support wasn’t scheduled to come into work until that evening but he gave me his phone number. When I called, the Manager promised that he would personally “pull” my package and that it would be at my local post office the following day. However, when I went there no one could find it. I called the manager at the Morgan Facility again and he apologized, saying that the package had been sent to the wrong post office because of some sort of problem with the address and had been returned to the Morgan. He assured me that I would receive it the next day, September 25th.

Late the following morning I returned to my local post office and, once again, they could not find the package. Uttlerly frustrated, I was at a loss as to how to proceed. The print had been only eleven blocks from me and I still couldn’t lay my hands on it! It was at that point that I saw the mail carrier who delivers to my building. I explained the problem to him and asked if he had seen a mailing tube. “Yes, yes,” he said. “I just delivered it but I almost didn’t because something about the address didn’t look right.”

I ran to my building and found the package there. I finally had the print but I wanted to solve the mystery of why it had bounced around the postal system for forty-two days before I received it.

Throughout the print’s excellent adventure, I had been in contact with Thomas Greyeyes who said that if I didn’t receive the print he would replace it. However, it just didn’t seem right to me that an artist should lose money because of glitches in the postal system and I wanted to know why it had happened.

Based on conversations I had with staff at various post offices between August 15th and September 25th, the package ran into difficulties because of “inherent problems.” When the artist mailed the print he used a cylindrical tube but no one at the post office informed him that this would slow delivery because postal scanners are only programmed to accept and scan “squared” mailing tubes. Cylindrical tubes have to be hand pulled at each sorting facility. Complicating matters was the fact that, at some point, one of the tubes’ plastic end seals had fallen out and someone had replaced it with an X made of cellophane tape. But what wasn’t quite right with the way the tube was addressed? Upon closer inspection, I realized that, as written, the last two numbers of the zip code – 11 – could be misread as 4. This would cause the postal scanners to redirect the tube until it could be checked by a postal employee, slowing down the package’s progress through the system.

One of the joys of collecting is that each piece has a memory and story connected to it. Usually, acquiring a piece for my collection is quite straightforward. However, sometimes the process can be complex. Finding a stellar example of an artist’s work might be complicated and involve a quest over a number of years, as was the case with Alice Cling. At other times, it might be difficult to find an artist’s work through the usual channels such as galleries, shops or art markets, as happened with Sonya Kelliher-Combs. Perhaps the most difficult situations arise when events transpire that are out of the collector’s control. That certainly happened with Red Raven, Red Raven by Thomas Greyeyes. I learned that sometimes a collector must have an attitude of persistence, a spirit for adventure and the ability to be resourceful.