Collector's Corner

AN EXCELLENT ART ADVENTURE: Acquiring Works on Paper by Allan Houser and Harry Fonseca

As a collector, I am always interested in acquiring new works. For many years the focus of my collecting was historic and, then later, contemporary pottery created by Native American artists. However, sometime around 2008 I became aware that a number of Pueblo ceramic artists, such as Jason Garcia, Diego Romero, and Virgil Ortiz, were also creating works on paper that were very affordable. Not long afterward, Andrea Hanley, who was working as a gallery director at the time, encouraged me to broaden my collecting by considering works on paper by Native artists of all backgrounds, not just Pueblo artists. I credit Andrea with inspiring and supporting the Native American works on paper portion of my collection, which now includes ledger drawings, drawings from the early to late 20th century as well as scores of contemporary pieces. This past summer, after some exploration, I decided to add pieces by Allan Houser and Harry Fonseca to the collection. I came to my decision about each artist in different ways.

Untitled double-sided drawing, recto (HF1995.1-334X.a.b.D) by Allan Houser, ChiricahuaApache pencil and blue ball-point pen on paper on paper from the artist’s sketchbook, 9“ x 12“ (circa 1983). Collection of E. J. Guarino

While in Santa Fe, I had been in the Allan Houser Gallery many times and I did remember that many years ago I had seen works on paper by Houser in an exhibit at the Taylor Museum for Southwest Studies in Colorado Springs. Although the artist is probably most noted for his sculpture, he also produced an abundance of works on paper. I decided to explore the Houser Gallery website and found a number of drawings that interested me. I E-mailed David Rettig, Curator of Collections for Allan Houser Inc., to inquire about pricing. However, the drawings I had selected were far beyond what I could afford and, when I explained this, Mr. Rettig suggested that I might be interested in sketches stating, “I do have a sense of what you are looking for and if you don’t find it too tedious looking through jpg images, I could start by sending 20 or so images from which we could refine a selection to bring to the downtown gallery. These will be sketches as opposed to the more fully rendered larger drawings.”

David Rettig sent me twenty images at a time, sometimes forty, for me to consider. After much thought, I narrowed my choices to four possibilities, which I would see when I arrived in Santa Fe. Of these I liked the ones that seemed less finished. I preferred the ones that have a rawness, as if the artist were just putting things down on paper as they came to him, without thinking too much about what he was drawing. However, the two sketches that most interested me were problematic. One was a double-sided sketch, which had a crease in it. Mr. Rettig was of the opinion that “the fold is part of the work, as I venture Allan had previously folded the paper, but did the drawing on the reverse as well. I don’t think it affects the long-term archival preservation”. It seems to me that this was something that the artist did himself. It is part of the history of the creation of the piece and it also shows Mr. Houser’s creative process.

I do try to exercise all necessary caution when acquiring works for my collection, but I think curators and conservators are more rigid than collectors.

Untitled double-sided drawing, verso (HF1995.1-334X.a.b.D) by Allan Houser, Chiricahua Apache, pencil and blue ball-point pen on paper on paper from the artist’s sketchbook, 9“ x 12“ (circa 1983). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Untitled double-sided drawing, verso (HF1995.1-334X.a.b.D) by Allan Houser, Chiricahua Apache, pencil and blue ball-point pen on paper on paper from the artist’s sketchbook, 9“ x 12“ (circa 1983). Collection of E. J. Guarino

David Rettig offered to get yet another opinion and contacted Jo Anne Martinez-Kilgore of Cariño Conservation who wrote, “From my point of view, the crease makes it more interesting as it shows process by the artist. But I am not a curator. It seems to me that one side was drawn before the crease and part of the other side after . . . .”

When I arrived in Santa Fe I went to the Allan Houser Gallery and looked at the sketch. From my point of view, I did not think that the fold posed a problem and I acquired the work. I felt that the sketch was very strong, reflecting much of the subject matter in the Houser’s sculptures. The fold is part of the history of the creation of the piece and it also shows Mr. Houser’s creative process.

Untitled drawing (HF1995.1-476K.D) by Allan Houser, Chiricahua Apache, pencil and blue ball-point pen on Hammermill Bond paper from the artist’s sketchbook, 9h“ x 12“w (circa 1983). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The issue with the second work I was considering was far less problematic. This is an individual drawing on thin Hammermill Bond paper. In the upper right quadrant the watermark is visible in the most heavily shaded areas. Also, there is a very slight crease in the upper right quadrant to the edge of the paper. Some collectors are sticklers about such things; I am not. I enjoy the quirky things that artists do. It indicates that they are creating from personal inspiration rather than for the marketplace.

Untitled drawing (HF1995.1-476K.D) by Allan Houser (detail). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Untitled drawing (HF1995.1-476K.D) by Allan Houser (detail). Collection of E. J. Guarino

I have a friend who gets perturbed because I have works in my collection that are on butcher paper, paper bags, and such. His concern is that they were not made with archival materials. I often remind him that the Abstract Expressionists often used house paints and other fugitive elements to create art. Of course, this has been a nightmare for contemporary curators and conservators, but the work of the Abstract Expressionists, nonetheless, sells for millions of dollars. As a collector, I don’t particularly concern myself with such matters. I feel that, if necessary, they will be addressed by some future curator. My job is simply to collect the best works of art I can for later generations to enjoy.

I looked carefully at the sketch and decided that the artist had chosen to draw on this sheet of paper despite the watermark and that was fine with me. I particularly liked this sketch because, like the double-sided drawing I had chosen, it reflected the artist’s sculptural interests. Looking at the piece, one immediately gets a sense of the artist working out on paper the ideas he had for his large sculptures. Often collectors overlook sketches, dismissing them as unimportant. I feel quite differently believing that they give us a unique insight into an artist’s creative process.

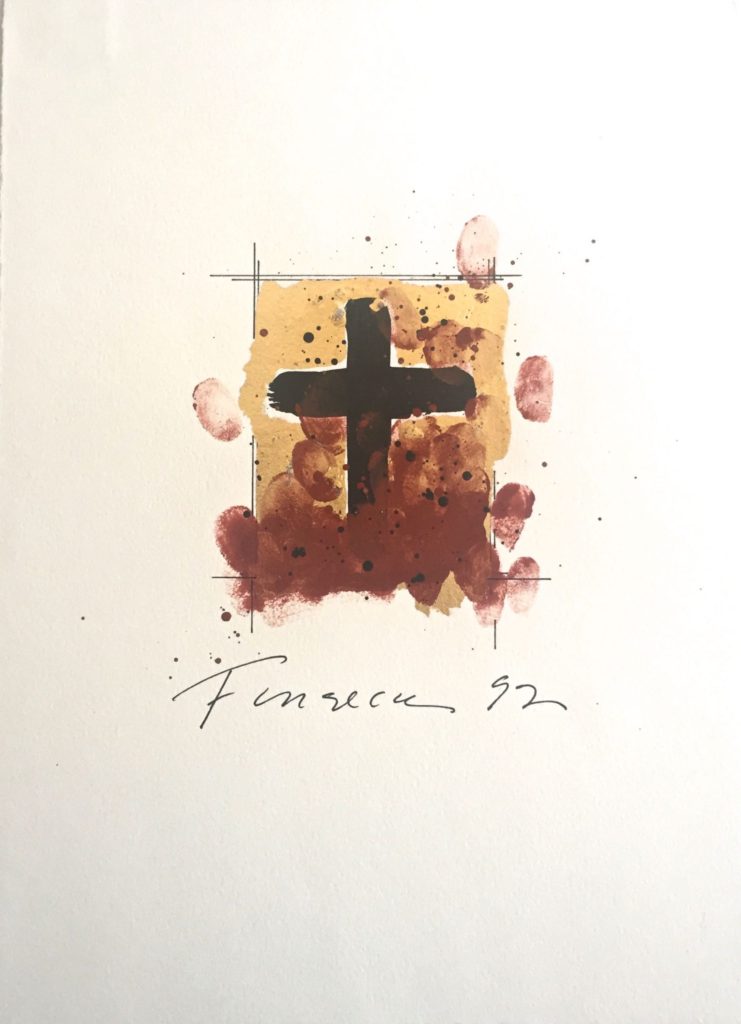

Discovery of Gold and Souls by Harry Fonseca, Nisenan Maidu, Hawaiian, and Portuguese, original painting on paper, gold leaf, cinnabar paint and acrylic paint, 11“ x 15“ (1992). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Before arriving in Santa Fe, I met with Jennifer Complo McNutt, Curator of Contemporary Art at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis, and was graciously given a tour of In Their Honor, an exhibit curated by McNutt, which pays homage to the five Eiteljorg Fellows who have passed away: Allan Houser (Warm Springs Chiricahua Apache), George Morrison (Grand Portage Band Ojibwe), Harry Fonseca (Nisenan Maidu/Hawaiian), John Hoover (Aleut), and Rick Bartow (Mad River Wiyot). The exhibition particularly piqued my interest not only in Allan Houser, but also to consider works by Harry Fonseca. On a number of occasions I had seen drawings by Fonseca of Coyote, a figure he often used for social and political commentary as well as for humorous effect. However, these works didn’t particularly appeal to me. Since I was going on to Santa Fe, I decided to contact Dr. Bruce Berstein, Executive Director of the Ralph T. Coe Center for the Arts. As one of two trustees for The Harry Fonseca Trust, he had offered to take me through the Harry Fonseca Archives to see if there might be some works that interested me.

As I looked at scores of drawings and paintings on paper, I came to appreciate what Fonseca was attempting to do with the character of Coyote. However, it was other works that held more appeal for me. I was particularly intrigued by the works in the Discovery of Gold and Souls Series. The symbolic imagery is visually striking. The artist achieved this using only three colors – black, gold, and red. In a very powerful, yet subtle way, Fonseca commented on the quest for gold and the conversion of souls that resulted in much bloodshed. I looked through the series and decided upon a piece that bore the fingerprints of the artist.

Untitled study of rock art from Utah from the artist’s sketchbook drawn on site on 9/16/92, 10.75“ x 13.75“ (1992). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The second work I chose by Harry Fonseca excited me for different reasons than Discovery of Gold and Souls. It is a page directly from the artist’s sketchbook and the date recorded on it – 9-16-92 – indicates exactly when it was produced.

The sketch is a study of rock art from Utah that was drawn on scene. The images strongly suggest that Fonseca was at a Fremont culture archaeological site. The Fremont were a pre-Columbian group named for the Fremont River. It was near this waterway that Utes and Navajo discovered the first sites connected with these people. The Fremont inhabited what is today Utah as well as parts of Nevada, Idaho, and Colorado from the 1st to the 14th century AD. The Fremont culture was made up of diverse groups, some of whom lived in small, scattered communities and others inhabiting large villages. They dug pit houses as well as dwellings made of rock and mud. The Fremont grew corn and beans and also hunted large and small animals with a bow and arrow. Contemporary people are particularly fascinated by the petroglyphs they created of eerie figures that have an otherworldly quality. To some, these depictions evoke beings from outer space.

Fonseca was fascinated by petroglyphs, especially those found in California and Utah. The influence of rock art can be seen in the artist’s Stone Poem Series and his In the Silence of Dusk Series as well as his painting The Maidu Creation Story. Knowing the importance of rock art to Foncseca’s work, I felt that the addition of a sketch of petroglyph figures would be an important addition to my collection.

Although I had contemplated adding works by Harry Fonseca to my collection for quite some time, the opportunity to do so only recently presented itself. Allan Houser’s work on paper made an impression on me at that long ago exhibit at the Taylor Museum for Southwest studies, but only in the last year did I act upon acquiring a work by the artist. Often with collections, things take a while to unfold. Many years passed before pieces by Harry Fonseca and Allan Houser entered my collection, but it was worth the wait.