Collector's Corner

CLOTHES FOR A POST COLUMBIAN WORLD: Jaune Quick-to-See’s Paper Dolls Series

Simply put, a paper doll is a printed or painted paper figure, which has an accompanying paper wardrobe. Often, this two-dimensional creation and its array of outfits were meant to be cut out. As early as the mid-1700s, paper dolls were being produced in London, Paris, Berlin and Vienna, all considered fashion centers of the period. In fact, the first paper doll of a celebrity, published in the 1830s, was of a ballerina. Paper dolls of royals and political figures, which were often satirical, have also been produced.

Generally intended for children, these little mannequins have also been popular with adults who collect them because their clothing reveals much about fashion, culture, and history. There are paper dolls representing adorable babies, cute children, fashionably dressed women, cartoon and comic book characters, and celebrities from opera, theater, film, and TV.

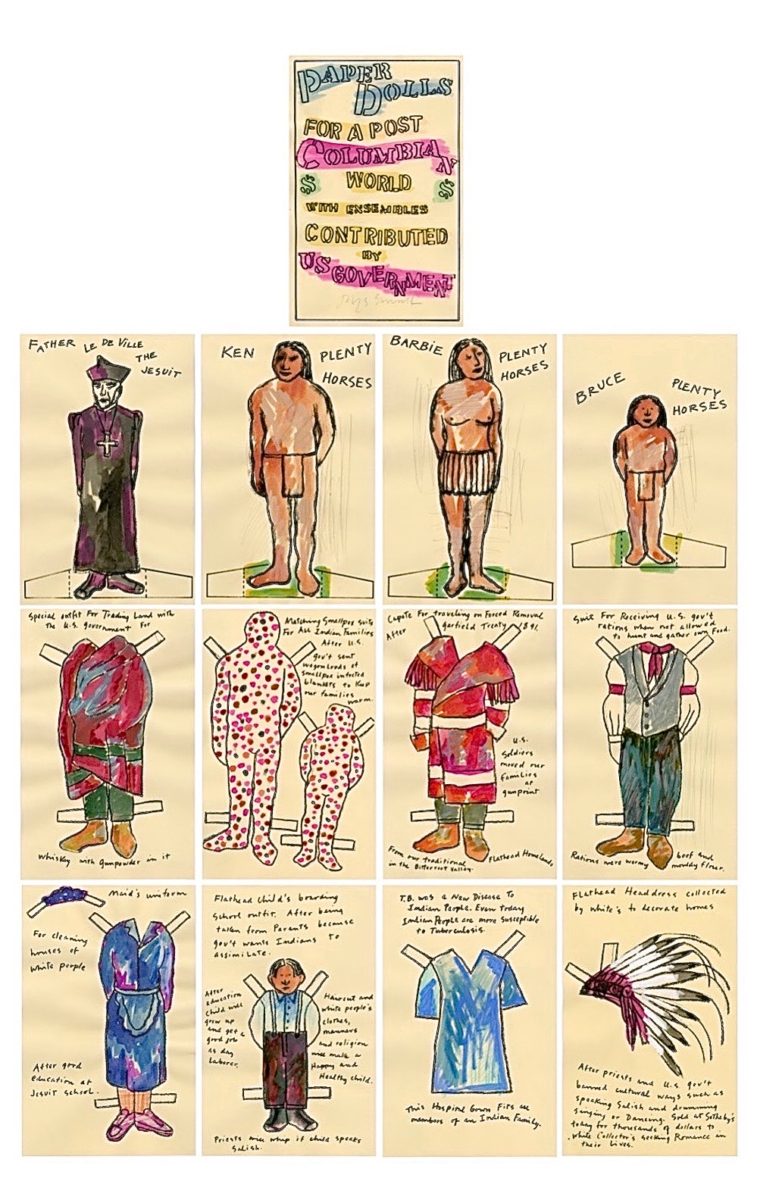

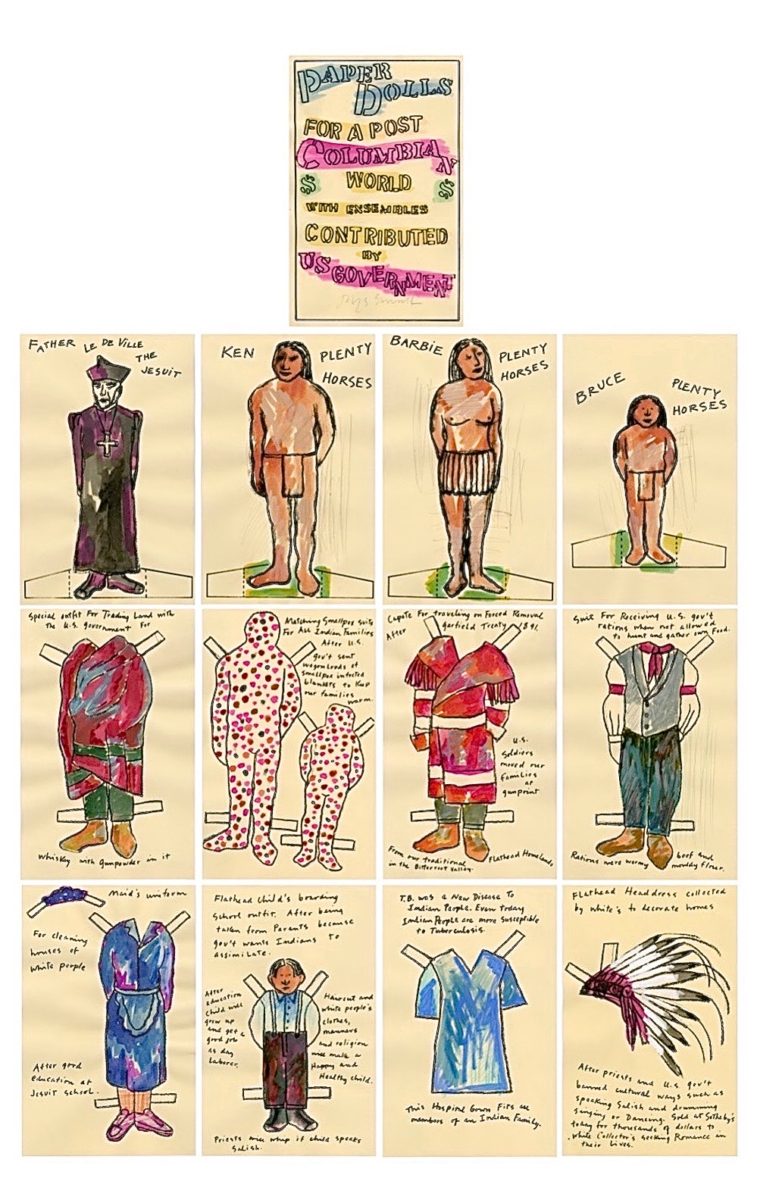

Sheet 1 of Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (1991).

At first, it might seem strange that Jaune Quick-to-See Smith would use the concept of paper dolls in her art, which explores profound social, political, and historical themes, some of which are quite controversial. However, as an artist, she often uses humor to invite audiences to consider subjects that are thorny and often painful. Paper dolls are a perfect vehicle for the artist, allowing her to present difficult aspects of American history in a non-confrontational way.

Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, watercolor, pencil, and Xerox on oak tag paper, 13 sheets, each sheet 17” x 12” (1991).

Divided into thirteen sheets, Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government presents the horrible things the United States government did to Native Americans but does so in a tongue-in-cheek manner. As with all satire, the intent of Paper Dolls is to hold these abuses up to ridicule and criticism so that the public is made aware of the mistreatment of Native Americans. The thirteen sheets that comprise Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government form a narrative. According to the artist, the work is “. . . a story about my tribe and my family. The government gave the Catholic Church (ours were Belgian Jesuits) the right to take children away from our families and not allow the families or children to visit each other.” The main characters of Paper Dolls are Father Le de Ville, a Jesuit, and the Plenty Horses Family – Ken, Barbie, and their son, Bruce.

Sheet 2 of Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government: Father Le de Ville.

The villain of Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government is Father Le de Ville. As his name plainly indicates, he is the source of many evils. He is the only character who has no change of clothing. He is as he is. There are no outfits for the viewer to project upon him.

However, the history of the Jesuit Missionaries among what are today the The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes is complex. The Salish invited the Jesuits to come to their lands, believing that they had some special, unknown spiritual power. X̣alíqs (Shining Shirt), a Salish prophet, had a vision of men wearing black robes who would bring his people new medicines and a different way of praying, but he also warned that afterward the world would “fall to pieces.” A group of Mohawk Iroquois, who worked for the French Canadian fur traders, also told them of men, whom they called the Black Robes, who had brought them a new religion. Believing all these things to be an omen, the Salish leaders sent delegations to St. Louis in 1831, 1835, 1837, and 1839 to ask that a Black Robe be sent to teach them the powerful new medicine they had heard about. The first three deputations never reached their destination 1,500 miles away, having been killed by disease and by Sioux warriors as they traveled through their territory. The fourth group, having reached St. Louis, was promised a Black Robe and in 1841 Father Pierre-Jean de Smet arrived in the Salish homeland.

The spiritual beliefs of the Salish and neighboring tribes was in sharp contrast to those the Jesuits professed. Coyote and other sacred beings had taught the Salish the proper way to live in the world. As hunter-gatherers, they migrated seasonally around what is today western Montana and had a close relationship with the earth and the plants and animals that lived upon it. Owning the land and living in one place was a concept that was foreign to the Salish and their way of life.

In order to accept Christianity, many Salish gave up their spiritual beliefs and practices, their traditional way of sustaining themselves, their language, and many other aspects of their culture. Intent on conversion, the Jesuits considered Salish teachings a form of paganism that had to be eliminated.

Around the time that many of the Salish converted to Christianity they also were able to ward off attacks by warriors of the Blackfoot tribe. They attributed this to the spiritual power of the Black Robes. The Salish felt betrayed when the Jesuits began proselytizing among the Blackfoot, believing that their enemy would now also have this special power. This caused many Salish to become openly hostile to the Jesuits and their religion.

Ironically, today a large percentage of The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, who live on the Flathead Reservation, take part in Catholic services while many also observe traditional spiritual practices and see no conflict in doing so.

Sheets 3, 4 and 5 of Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government: The Plenty Horses family – Ken, Barbie, and Bruce.

As the protagonists of Paper Dolls, it is the Plenty Horses family that reveals to us the injustices committed against the Salish. By presenting the narrative as paper figures that can be dressed in a variety of outfits, at least mentally, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith makes the viewer complicit in the injustices done to her people. In a cerebral way, the piece forces the audience to interact with it.

The artist gives the three family members typically mainstream American names. The names of the parents – Barbie and Ken – are a sly and humorous

reference to Barbie and her boyfriend Ken, iconic toys that transformed the dress-up doll from a two-dimensional figure to one that was three dimensional. “. . . my Ken and Barbie Plenty Horses (actually a tribal name we don’t have anymore but in the later 1800’s it was a family there,) so I commemorate them,” Jaune Quick-to-See Smith stated. All of the inequities suffered by the Salish are represented by the various clothes that can be used to dress the Plenty Horses family.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith uses sheets six through thirteen of Paper Dolls to make statements, which present historical facts concerning the often genocidal treatment of the Bitterroot Salish, Upper Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai tribes. The Bitterroot Salish and the Upper Pend d’Oreille became the Confederated Salish and together with the Kootenai eventually became The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, which today comprise the Flathead Reservation.

Sheet 6: “Special outfit for trading land with the U. S. Government for whisky with gunpowder in it. “

One of the ways that the fur traders got better deals and settlers were able to gain control of Native lands was to offer Native Americans whiskey, in some cases laced with gunpowder. Since one of the ingredients in gunpowder was saltpeter (potassium nitrate), the explosive may have been added to the whiskey given to Indians because of the mistaken notion that it would increase the potency of the alcohol and that it would also make Indians passive by affecting their libido. In essence, alcohol was employed as a chemical weapon, allowing fur traders and others to have a distinct advantage when bargaining with their Native American counterparts. In small amounts, ingesting gunpowder is not particularly poisonous. However, large amounts can cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache, dizziness, confusion, convulsions, nausea and vomiting, labored breathing, blue lips, fingernails and skin, and even unconsciousness.

Sheet 7: “Matching smallpox suits for all Indian families after the U.S. Gov’t sent wagonloads of smallpox infected blankets to keep our families warm.”

Long before Native people ever saw a European they felt the effects of their arrival through the pathogens which proceeded them. Unknowingly, the new arrivals had brought with them chickenpox, smallpox, measles, mumps, cholera, diphtheria, influenza, malaria, scarlet fever, whooping cough, typhoid, tuberculosis, the common cold, leprosy, yellow fever, the bubonic plague, and gonorrhea. Of these diseases, smallpox was the most devastating. Unlike the Europeans, Native populations had no inherited immunity to these illnesses. Within the 100 to 150 years following the arrival of Columbus and his men, it is estimated that eighty to ninety-five percent of the Native population was wiped out. Germs were able to move quickly in the Americas because of the extensive trade networks that existed among Native peoples.

Shockingly, not all of the epidemics were accidental. The British military and, later, the U.S. Government used disease as a form of biological warfare. During the French and Indian War, British commanders saw to it that their Indian enemies were given smallpox infected blankets. In 1763, Jeffery Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst, Britain’s commander-in-chief wrote the following to Colonel Henry Bouquet, “You will Do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of Blankets, as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race.”

The effect of the new diseases had both direct and indirect consequences. Besides the death total they brought about, the various sicknesses shattered Native populations in other ways – there were fewer people to hunt, gather, plant, and to perform other tasks required to keep communities viable. In addition, the death of so many people caused a loss of cultural knowledge and traditions, something whose effects are still being felt today.

With regard to the Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s tribe, in Email correspondence, the artist stated, “My father told me about the trade canoes/smallpox blankets and him seeing the elder men who lived through it, bald because smallpox made them lose their hair and Indians generally don’t go bald. So I remembered that.” Smallpox came to the Flathead tribe from two directions – from St. Louis via the Missouri River with trade goods and from Vancouver via the Columbia River.

Sheet 8: “ Capote for traveling to Forced Removal after Garfield Treaty 1861. U.S. soldiers moved our families at gunpoint from traditional Flathead homelands to the Bitterroot Valley.”

Throughout the 1800s the policy of the United States Government with regard to Native Americans was that they were a hindrance to the concept of Westward Expansion. Tribes were forcibly removed from their traditional homelands to accommodate non-Indians. Men, women, children, and the elderly were forced marched hundreds of miles by the military to new lands dictated by the American Government. Sometimes the Government moved a tribe several times, often to areas that were vastly different from their traditional lands.

After the Civil War, many non-Indians encroached on tribal lands in what is present-day Montana, where they established farms. In spite of this, none of the tribes committed any acts of violence against the newcomers. Nonetheless, the government was determined that they should be moved. In 1855, the Bitterroot Salish (Flathead), Pend d’Oreilles, and Kootenai met with territorial governor Isaac Stevens in western Montana to discuss a treaty. Stevens wanted to consolidate the three tribes, together with other tribes, onto one reservation. It was of no consequence to him that although the Salish and the Pend d’Oreilles were Salish-speaking, the Kootenai spoke a different language and did not have a particularly friendly relationship with the two other tribes. When Chief Victor (Plenty-of-Horses) refused to sign the treaty, his signature was simply forged.

On October 15, 1891, after years of near-starvation and mistreatment by the United States Government, troops from Fort Missoula forced Chief Victor’s son, Charlo, and 157 tribespeople, all that remained of the Bitterroot Salish, to move to the government designated Flathead Reservation.

The name of the Plenty Horses family in Paper Dolls is a reference to Chief Victor who was also known as Plenty-of-Horses. Visually, the use of the capote is a reminder of the first encounters between the Flathead people and whites. Early on, both Natives and the French Canadian fur traders made wool blankets into long coats with hoods, which were capped capotes.

Sheet 9: “Suit for receiving U.S. gov’t rations when not allowed to hunt and gather our own food. Rations were wormy beef and moldy [sic] flour.”

Before their mass extinction in the 1800s, the bison population in North America numbered in the tens of millions, but by the end of the century, less than 100 remained in the wild. The bison were killed by white hunters for their skins and tongues while the rest of the animal was left behind to rot. Later, the bones were collected and shipped to the East where they were ground up to be used as fertilizer. In addition, the railroads advertised excursions for “hunting by rail.” Hundreds of bison were shot from moving trains as a sport, leaving the bodies of the animals where they fell. The extermination of the American Bison had an even more sinister motivation: By eliminating a major food source for tribes dependent upon the buffalo it would make it easier to control them. “When the government was trying to get rid of us,” Jaune Quick-to-See has stated, “one way was to get rid of all the buffalo and hope we starved to death and if that didn’t work then another reason was to keep us from hunting, which was an important part of our culture, in other words, to keep us confined at the fort or to keep us imprisoned so they could control us.”

Prevented from hunting and gathering, tribes were forced into dependency upon the U. S. Government for food. “Trade canoes brought moldy flour upriver to our tribe,” Jaune Quick-to-See Smith stated, “and we made fry bread out of it.”

Sheet 10: “Maids uniform for cleaning houses of white people after good education at Jesuit school.”

Despite trying to assimilate to Anglo-American ways, Native Americans, particularly females, were usually relegated to subservient roles. After attending white-run schools, most often forcibly sent away to boarding schools, young men and women were stripped of all aspects of their culture – religion, foods, clothing, hairstyles, language, and traditional knowledge. The Flathead tribe, which was relegated to a reservation, lived for many years close to starvation. In spite of attending Jesuit schools, graduates had little chance of making a good living among the settlers. In order to survive, Native women often became housemaids, laundresses, and babysitters. The statement on Sheet 10 is ironic. “The government said Indians were getting a good education at the church schools,” Jaune Quick-to-See Smith stated. “What I show is that a good education meant my family and my tribe were trained to be put into servitude for the white people in Missoula. My family was taught to be gardeners, housekeepers, nannies, do laundry, clean brass, be kitchen help, etc. I show their outfits for these jobs of menial labor because it was thought Indians could not be educated. Also, the church became wealthy with all this slave labor. My tribe tended orchards, cattle, gardens, cleaned, scrubbed, did laundry, and cooked for the priests and the nuns.”

Sheet 11: “Flathead child’s boarding school outfit. After being taken from parents because gov’t wants Indians to assimilate.”

“After good education child will grow up and get a good job as a day laborer.”

“Haircut and white people’s clothes, manners and religion will make a Happy and Healthy child.”

“Priest will whip if child speaks Salish.”

Of the eight sheets in Paper Dolls that offer historical commentary, Sheet 11 contains the most statements by the artist. In addition, it is the only sheet that shows one of the characters wearing one of the costumes. Kevin Plenty Horses is dressed as a child who has been forced to attend a boarding school.

In a speech he gave in 1892, Col. Richard Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian School, stated “. . . all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” The boarding schools used a number of methods to carry out this mandate.

One can only imagine the emotions felt by Native children when they were forcibly taken from their parents and sent hundreds of miles away to landscapes that in no way resembled their homeland. Beginning in the late 1800s, this policy existed well into the 20th century. Any parents who did not cooperate were denied government-supplied rations and clothing.

The boarding schools were run based on a strict military model. The children were forbidden to speak their Native languages and were physically disciplined if they did so. They were prohibited from using their own names, wearing their own clothing or practicing their religion and culture. Given Anglo-American names, they were required to wear what amounted to a standard-style Euro-American uniform. Students who arrived with long hair, which was spiritually important in many Native cultures, were given American-style haircuts. It has also come to light that many of the children who attended the residential schools were subjected to physical, mental, and sexual abuse. Many students repeatedly ran away. “My father” Jaune Quick-to-See Smith stated, “ran away over and over until they didn’t come to get him anymore. He wasn’t the only one who did this but with some they sent them to Spokane to another school or to a school in Oregon. The idea was to take the culture out of the Indian, force them to speak English. My aunties and uncles went there too.”

Disease was rampant at the schools because the students lived in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions and were poorly fed and overworked. A large number died of tuberculosis, pneumonia, measles, and the flu. Many of the children never returned to their homes and, all these years later, their fate remains unaccounted for by the United States government.

Sheet 12: “T. B. was a new disease to Indian People. Even today, Indian People are more susceptible to tuberculosis” “This hospital gown fits all members of an Indian Family.”

Whether or not tuberculosis existed in North America before the arrival of Europeans remains unclear, and the topic continues to be a source of medical debate. However, even if the T.B. bacterium had been present, its effects were negligible. One reason might be that Native North American peoples did not live crowded together in large numbers. That changed when tribes came into contact with Europeans and were later forced by the U. S. Government onto reservations and parents were compelled to send their children to boarding schools. In both situations, overcrowding, poor nutrition, and inadequate medical care created the perfect storm for tuberculosis to gain a strong foothold among Native Americans. By 1900, the disease had become one of the most serious health problems for American Indians. Often, children thought to have tuberculosis were sent from residential schools to a T.B. sanatorium where they were kept for years. Many were the subject of experiments without the consent of their parents who were hundreds of miles away and had no knowledge of the procedures being performed on their children.

Sheet 13: “Flathead headdress collected by white’s [sic] to decorate homes after priests and U. S. Gov’t banned cultural ways such as speaking Salish and drumming, singing and dancing. Sold at Sotheby’s for thousands of dollars to white collector’s [sic] seeking romance in their lives.”

Sheet 13 contains one of the most ironic and caustic statements in the series. Many wealthy collectors don’t buy from living Native America artists, preferring to acquire historic and pre-historic works. Since there may be little information associated with such objects they often lack context. These works all have stories that go with them and some collectors seem to forget that there is a person behind the art. Often, such collectors have no connection with Native American culture beyond the artifacts they collect.

Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World, by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, MT, pastel, 30 x 22 inches (1991).

In 1991, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith also produced a single sheet version of Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government, but with two notable additions: dollar signs and a box under which is the following statement: “Box for U.S. Gov’t commodities such as canned milk which gives us lactose intolerance; white sugar which gives us diabetes; white flour which gives us wheat allergies and lard which gives us gallbladder trouble.”

Cover of “How to ’92: Model Actions for a Post-Columbian World.”

“How to ’92: Model Actions for a Post-Columbian World,” a pamphlet for cultural activism for 1992 and beyond was produced during the quincentennial of Columbus’ entry into the Americas. Sheets 7 and 13 of Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government were used to create the front cover.

Although Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government makes strong political statements, the work is not didactic. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith takes potentially explosive material and through the use of irony presents it to the viewer in a humorous, accessible, non-threatening manner. In this way, the artist engages the viewer with controversial subjects, addressing multiple social, political and historical issues in the guise of a benign, children’s plaything. What draws viewers in is something that they perceive as familiar. It is only on closer inspection that they realize Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s intent. To mainstream audiences it may seem odd that the artist chose a toy as a medium to explore such profound themes, but by doing so, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith has found a way to involve an audience in a non-confrontational manner, allowing for a discussion of difficult and often painful subjects.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith for generously providing a wealth of information about her art.