King Galleries Blog

Russell Sanchez: Contemporizing the Pueblo Pottery Past

|

|

|

|

Contemporizing the Pueblo Pottery Past

How does Pueblo pottery best embrace its traditions and historic past as it enters the new era of modern ceramic influences? This question, certainly more relevant today than the old trope of “what is traditional pottery,” underscores the future directions and impact of this important Native art form. This article uses the recent work of one potter, Russell Sanchez, as an example of how an artist can reclaim cultural and historic foundations to create an interesting and expansive focus for their art in the world of contemporary clay.

Russell Sanchez (b. 1963) grew up surrounded by some of the greatest modern pottery making influences and legacies in his native San Ildefonso Pueblo. To contextualize his background, Russell is a great-great-grandnephew of Ramona Sanchez Gonzales (1885-1934) and a great-grandnephew of Rose Gonzales (1900-1989). He learned to make pottery from Rose, who taught him the basics of traditionally coiling forms, polishing and firing. Anita Da (1920-2005), the wife of Popovi Da (1922-1971), was also influential in guiding his early artistic career. After Popovi Da’s passing in 1971, Anita continued to operate their studio and gallery, which was located on the pueblo. It was considered one of the best sources for collectors to find not only work by Maria Martinez (1887-1980) but also younger Native potters. Anita provided Russell with insights on creating innovative and quality work. Her son, Tony Da (1940-2008), taught Russell how to inlay heishi beads, two-tone his pottery, inset stones and sgraffito (or etch) designs into the surface of the clay before it is fired. Russell had unique access to the available techniques, both innovative and traditional, at the start of his career.

Surrounded by this talent and guided by their experience, Russell began to create technically high quality pottery using traditional clay and firing techniques. It is now obvious that the artists around him saw an innate talent which manifested itself in extraordinary pottery throughout the 1980s and 1990s. However, it is his work after 2000 which becomes among the most interesting of his career to date. Sanchez became interested in historic San Ildefonso pottery from the 1880s to the early 1900s. Kenneth Chapman’s The Pottery of San Ildefonso Pueblo offered initial insight into the variety of early designs. Russell was most fascinated by those elements which had disappeared from the painted lexicon of contemporary San Ildefonso pottery. Additional museum research provided a hands-on opportunity to better understand how these historic pieces were formed or painted. Russell also sought out family and friends from the Pueblo who still remembered the older potters from the 1920s to 1940s period. This was an era of extraordinary innovation and creativity at the Pueblo. Over the course of nearly a decade Russell was able to compile an exceptional and unique art-identity with San Ildefonso as the rich source for his contemporary pottery.

Family: Rose and Ramona

Rose Gonzales is considered the first potter at San Ildefonso to begin carving into the surface of the pottery in the early 1930’s. Her signature form was a water jar with an elongated neck and low shoulder. Her style of deep carving, almost a cameo style relief, also utilized the matte negative space surrounding her designs. Russell often uses her signature shape. He elongates the neck and modifies the shoulder. The basics of the form remain intact while the proportionality varies with each piece. His imagery is secondary to the shape, which is the immediate visual identifier of Rose’s legacy.

|

|

| Long neck jar by Rose Gonzales, circa 1960s | Long neck jar by Russell Sanchez |

Ramona Sanchez Gonzales was one of those early San Ildefonso innovators whose work has yet to be fully appreciated. Few pieces have survived in either public or private collections. However, she was distinctive in her painting style with intricately detailed patterns. These designs can be perceived as a precursor to the fine sgraffito on the surface of Russell’s pottery. Birds, animals and geometrics were all part of her imagery repertoire. Beyond her designs, Russell has taken her shapes as a starting point, expanding and refining their proportionality.

|

| Tall cylinder with bear lid by Russell Sanchez, 2015 (left) and canister with bird lid by Ramona Sanchez Gonzales, circa 1925-30 (right). |

Boxes

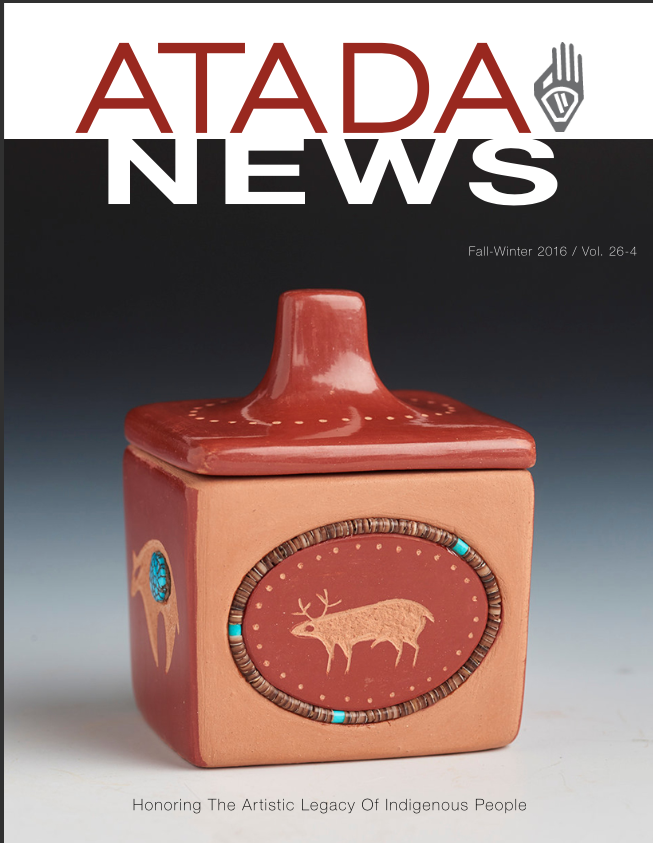

Boxes at San Ildefonso were originally inspired by the traditional square or rectangular corn meal bowls. The evolution into “cigarette” boxes with a square, rectangular or circular shape and a handled lid came during the mid-1920s. The boxes varied in painted designs and size but were part of the innovations surfacing with the newly created black-on-black and red-on-red style of pottery. Russell has challenged himself to recreate this difficult form with square sides and a flat lid. The square form creates additional stress on the vessel during both drying and firing which can result in cracking. Today Russell’s boxes are a refinement of form. The intricacy of their sgraffito designs are reflective of the tightly painted designs and subtle use of color in earlier pieces.

|

|

| Susana Aguilar (1876-1947) red-on-red box with additional white slip designs, circa 1920s. | Bear Lidded box with sgraffito designs and inlaid heishi beads and inset turquoise by Russell Sanchez, 2016 |

Gunmetal Firing

One of the distinctive visual cues to the collaborative pottery of Maria Martinez and her son, Popovi Da, was the gunmetal finish. This metallic appearance was achieved during the firing process. Popovi was uniquely able to consistently achieve this coloration. It was the result of how he combined ash, manure and regulated the temperature in the firing. Today, Russell is one of the few potters who is able to achieve similar consistency of success with his gunmetal firings. He is able to manipulate the outdoor firing and a combination of ash, manure and heat to achieve an exceptional metallic appearance on the surface of his pottery. The risk of breakage in firing remains high, but the stunning and highly desirable visual results are an important cultural legacy for him to maintain.

|

|

| Gunmetal jar by Maria Martinez and Popovi Da, circa 1960s | Gunmetal plate by Russell Sanchez, circa 2014 |

|

| Traditional firing by Russell Sanchez to achieve the gunmetal metallic appearance of his pottery by combining manure and ash (2014) |

A Foot and Form

There was a brief period around 1900 when pottery at Santa Clara, Ohkay Oh’wingeh (San Juan) and San Ildefonso Pueblos sometimes used “footers” on their pottery. This single ring of clay was added to the pieces to give them stability. The refinement of the ‘puki’ as a base for starting pottery is possibly a reason for their disappearance. Russell has incorporated a similar “footer” into some of his pottery for nearly a decade. The additional extension of the base accentuates his forms, creating both graceful and at times highly exaggerated shapes. While the base is narrow, the vessel remains amazingly stable.

|

|

| Jar with handles, indentions and foot at the base, circa early 1900s. Courtesy The Couse Foundation, 2012 001-016 | Water Jar by Russell Sanchez with footer base, 2015 |

Contemporizing the Past

There were numerous variations in pottery forms in the early 1900s which were based on Pueblo stories and culture. However, the arrival of a market for selling pottery gave potters incentive to stylize and personalize their pottery to make it more distinctive. Aesthetics became as important as the cultural foundations of form and design. These individualized elements also became the visual identifiers of specific potters and painters. Most recently Russell has found inspiration in the stories of the indented or “gourd” jars of San Ildefonso Pueblo. While they may be more famous by association with Santa Clara Pueblo potters SaraFina Tafoya (1863-1949) and Margaret Tafoya (1904-2001), they were also part of the styles found among the early San Ildefonso potters. Maria, Desideria Sanchez (1889-1982), Tonita Roybal (1892-1945) and others all created indented surfaces on their pottery. The indentions ran both vertical and horizontal and were primarily on the shoulder. The fluted or “rain drop” rim is another distinctive addition. Russell has taken these variations and contemporized them on his vessels. He has used both vertical and horizontal indentions and modified them for depth, angle and quantity.

The lesson from Russell’s recent works in clay is that Pueblo pottery from the last 100 years is not, as is often perceived, a limiting or restrictive factor for artistic creativity. The innovative pottery of the early 1900s is more a source of creative exuberance as potters such as Sanchez are able to seek out historic trends and modernize them. Russell remembers pottery-making advice from his great-aunt Rose who told him, “to take what came before and make it your own.” Just replicating the old forms or designs is not enough and therein lies a trap of losing the individual’s artistry to the demands of history.

The past and present should be able to work together. The inquisitive mind of the potter and his or her cultural connection to the clay should aid researchers to better illuminate the historic importance of pottery in Pueblo life. One would think that there would be an abundance of research and information on this early period, especially around the 1920s. However, the dominance of anthropology at the time limited the interest in recognizing individual potters as artists creating their craft. Today, historian, researcher, curator, artist and gallerist should all work in tandem to better understand these artistic legacies. This synergism is critical to providing a balanced and nuanced understanding of the past. Much as the early San Ildefonso potters were innovators and not simply revivalists, today’s Pueblo potters can take a lesson from their creativity. As they develop their own ideas they do not have to not simply replicate the past in order to be successful. In doing so, they will allow ceramics to persevere as a dynamic and vibrant art form.

|

| “Gourd” jar by Desideria Sanchez, 1930s, and indented jar with fluted rim by Russell Sanchez, 2016. |

|

| Maria Martinez making a “gourd” jar at the Palace of the Governors, 1912. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe. Negative Number 061764 |

|

| Russell Sanchez contemporized gunmetal fired Water Jar with gourd indentions and a fluted rim and gunmetal fired bowl with gourd indentions and bear lid (2016). |

Click here to view more pottery by Russell Sanchez.