Collector's Corner

NOW YOU SEE IT, NOW YOU DON’T: Collecting and Provenance

Whenever I lecture about Native art I always explain that as a collector sometimes one is given a great deal of information, sometimes just a little, sometimes none and, in some cases, misinformation. As a beginning collector, I was so delighted to acquire a piece I liked that it never really occurred to me to ask detailed questions about it. I just trusted that the person who was selling it to me had all the information available, no matter how brief, and that what they told me was correct. That’s probably how I ended up acquiring an African basket at an American Indian pow wow. As I became more serious and more knowledgeable as a collector I became aware of the importance of getting as much data as possible on each piece I was acquiring. This information is part of what is commonly called provenance. Ideally, if possible, the collector should know the title of the work, the materials used to create the piece, the artist, pueblo or tribal affiliation, measurements, the date the piece was produced and names of previous owners if any.

Bandolier bag by Samuel Thomas, Cayuga Iroquois, strawberries, strawberry flowers and hummingbirds design, green, red, white, gold/orange, and clear glass beads on red velvet, 84” L x 19” w (bag portion is 12” x 11,” handle is 72” long x 3.5” wide), (2003). Collection of E. J. Guarino

When I acquired a spectacular beaded Bandolier bag from artist Sam Thomas in 2003, it came with a great deal of information. In addition to basic curatorial data – artist, tribe, dimensions, year of creation – I received papers that told so much more about the piece, even including the size of the seed beads used to decorate it. Beads the artist had selected were 8/o (resulting in 13.5 beads per inch) and 10/o (16.3 beads per inch). The higher the number, the smaller the bead. Among the documents I received with the bag was an entry form for the June 7, 2003 21st Otsiningo Pow Wow, which contained the following description: “Red velvet Bandolier/shoulder bag/octopus bag 2003 velvet, deerskin, size 8/o & 10/o seed beads, brass sequins, cardboard, paper, interfacing.” Other papers revealed that the piece had been honored with Best of Show and had received the prestigious Jim Thorpe Award. It was more than any collector could expect.

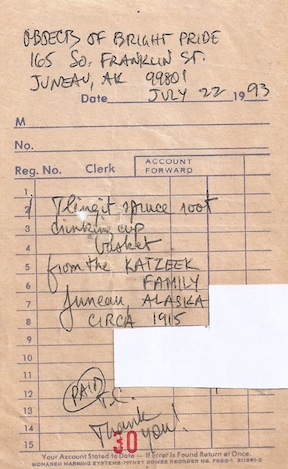

Tlingit spruce root trinket basket bottom from the Katzeek family (?) with bill of sale, Junea, Alaska, 2” x 4,” (circa 1915). Collection of E. J. Guarino

When collecting contemporary artworks, especially directly from the artist as I did with the Bandolier bag, it is much more likely one will get more information than with historic pieces. While on a trip to Juneau, Alaska in July 1993, I came across what I thought was simply a lovely Northwest Coast basket in the Objects of Bright Pride Gallery. The owner explained that it was a very special object – a Tlingit folding spruce root drinking cup circa 1915 that had been made by a member of the Katzeek family, which passed it from generation to generation before the gallery acquired it. In addition, I was told that the cup was woven so tightly that it could hold water and that in the past it was always kept moist so that it was pliable and could easily be collapsed. Noted on the bill of sale, which I always keep with a photo of piece, was the fact that the cup came from the Katzeek family, that it is made of spruce root, that it is from the Tlingit tribe and was made in 1915. However, in 2013 I sent an image of the basket to Stephen Lazarus, owner of Galerie Le Cedre Rouge/The Red Cedar Gallery in Montreal, who is an expert with regard to Northwest Coast art. According to Mr. Lazarus, once again, I had been given misinformation. I did not have a woven drinking cup but rather a trinket basket missing its lid. In a further Email correspondence, Mr. Lazarus added, “As far as I know, Tlingit and Haida baskets weren’t kept moist, but were moistened to collapse them when required. Drinking cups that I’ve seen were made of a thicker spruce root and, because quite small, not needed to collapse the way a twelve inch cooking basket would have.”

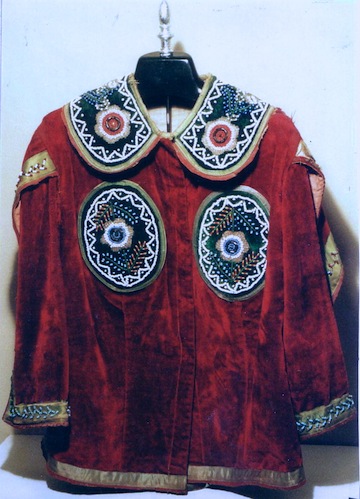

Velvet child’s cape, Iroquois, 23” h x 18” w (circa 1905-1910). Donated to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College from the Edward J. Guarino Collection in memory of Lynn Trusdell in 2009.

Velvet child’s cape, Iroquois, 23” h x 18” w (circa 1905-1910). Donated to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College from the Edward J. Guarino Collection in memory of Lynn Trusdell in 2009.

In many instances, especially when collecting historic works, very little information may be available. Often, what one is told is tantalizingly minimal. Such was the case when I acquired an Iroquois cape. The only facts about the piece I was given was the tribe of origin and a date, which may or may not be accurate. The rest I learned by observation and deduction. The cape was clearly made of velvet and decorated with a beadwork collar as well as two beaded medallions and beadwork trim. After measuring the cape it became clear that it had been made for a child. However, wanting to determine which branch of the Iroquois (Seneca, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Mohawk, Tuscarora) to which the artist belonged I contacted Dollores Elliott, a retired archaeologist who has the largest collection of historic Iroquois beadwork in the world. Elliott, who is an expert on historic Iroquois beadwork said in an Email, “It is . . . Mohawk made at Kahnawake (a reserve south of Montreal across the St. Lawrence River). By the amount of white beads I would date the cape at about 1905-1910. The first white beads were incorporated into Mohawk beadwork about 1900.” Ms. Eliot suggested that the cape may have been worn by a Native or non-Native entertainer or somehow connected with the Improved Order of Red Men, a non-Indian fraternal organization whose members dressed up in Indian Garb.

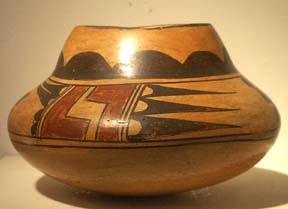

Polychrome pot, unsigned, Hopi, 3.5” x 6.5” (circa 1910). Collection of E. J. Guarino

On one of my many trips through the Southwest, I visited the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff that, by chance, was having a sale of pottery that had been donated to raise money, My eye was immediately attracted to a pot that had a wonderful patina. However, the only words written on the card that accompanied the the piece were “Old Hopi pot.” This lack of information did not deter me. At the museum, I asked if there was anyone who could tell me more about the pot and was told to write to a particular curator. When I returned home I photographed the piece and included it in a letter. I was particularly curious about when it might have been created and eventually learned that it had most probably been made sometime around 1910. Once again, I had to depend on observation and deduction. I measured the pot and, by looking at the multiple colors on it, I knew it would be termed polychrome. However, although I had no definitive explanation of what the decoration on the piece meant, most likely the abstract imagery represented rain clouds, lightning and bird’s wings.

Caddoan incised vase form pot, artist unknown, 6”h (circa 800-1700 A.D.). Collection of E. J. Guarino

After visiting archaeological sites in Mexico, Central and South America and the Southwest, I next became intrigued with the Mound Builder cultures. So, in 1998 I traveled through the Midwest to see sites associated with the Adena/Hopewell culture, the Fort Ancient Culture and the Mississippian Culture and to visit museums that were noted for their holdings of art produced by these ancient Native groups. On a stop in Bloomington, Indiana I ventured into Stewart’s, a store that sold guns and military items as well as antiques and “Indian Relics.” To this day, I don’t remember if a local directed me to the shop or if I simply wandered in by chance but I’m certainly glad I did. In one display case, among some poor examples of pottery from Mata Ortiz, Mexico, was a ceramic “vase” that looked remarkably like those produced by Mississippian Cultures that I had recently seen in museums. All the store owner could tell me was that the piece came from Oklahoma and that it wasn’t a forgery. Having learned over the years to trust my eye and my instincts, I bought the piece. Later research revealed that the pot had been made by the Caddo, a variant Mississippian Culture that inhabited what is now Eastern Oklahoma, Western Arkansas, Northeast Texas and Northwest Louisiana circa 800 to 1700 AD. The present day Caddo live in Oklahoma.

Beaded pouch with American flags and eagle on one side and a teepee and Indian man and woman on the other side, artist unknown, 9” x 8.75” at widest point (circa 1920s). Collection of E. J. Guarino

For a collector, perhaps worse than receiving no information is being given misinformation. I found this out four years after acquiring a remarkable Iroquois beaded pouch from a dealer, who years after her passing is still remembered across the country for her knowledge of Native American art. One side of the bag is decorated with images of two American flags and an eagle, making it extremely desirable to collectors. However, I found the imagery on the other side more intriguing. Although portraying a “Native scene,” it has little, if anything, to do with Iroquois culture. The male is wearing a feathered headdress worn by Plains Indians. Between the two figures is a teepee, a dwelling used by tribes on the Great Plains, not by the Iroquois who built longhouses. However, the Iroquois artist who made the pouch clearly understood that such a depiction would be instantly recognizable to her White customers as being “authentically Indian,” probably because, even in its infancy, this is how motion pictures portrayed Native Americans.

In 2006 the pouch was selected by Professor Karen Lucic of Vassar College to be included in “Forms of Exchange,” an exhibit at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center. As part of her research, Professor Lucic contacted Sam Thomas, a noted contemporary Iroquois beadwork artist and expert on historic Iroquois beadwork, whose pieces would also be in the exhibition. After studying the pouch, Mr. Thomas said in an Email that, based on the materials used, the piece had been incorrectly dated as circa 1880s and added, “The pink wool fabric was not used until after the turn of the century (1900), more so after 1905 and through the late twenties (1905-1929). Also, the bead size is indicative of dating, the large size beads came into designs around the same time periods. The beads used to ‘replace‘ the sprengperlen (Bohemian cut tubular beads) are a large, round, opaque pound bead as opposed to the earlier type which would date this piece after 1917. The factory in Gablonz that manufactured the cut tubular beads dates between 1860-1917. The factory closed in 1917 and the supply immediately stopped. By 1918 they were depleted. An alternative was to use the larger opaque bead. It would be more accurate to date this particular piece circa 1920s.”

Iroquois-style man’s jacket with matching leggings, Improved Order of Red Men Regalia; muslin, trade cloth, brass buttons, German silver medallions and horse hair; jacket: 34”L; leggings 39”L (date unknown). Donated to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College from the Edward J. Guarino Collection in honor of Michael Burns in 2009.

Four years after learning that the date I had been given for the Iroquois pouch was incorrect, research done by Professor Lucic and her students revealed an error of much larger proportions with regard to another piece I had donated to the Loeb Art Center. In 2010, Professor Lucic and her students in “A Different Way of Seeing: The Art of Native North America” were doing research on objects to be included in “Design in Living Things: Native Works from the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center,” an online exhibition. One of the pieces under consideration was a man’s jacket with matching leggings, which had been sold to me as being Oneida Iroquois, circa 1900, but was actually not Indian-made regalia for the Improved Order of Red Men, a non-Indian fraternal organization whose members dressed up in Indian garb. Ultimately, the jacket and leggings were kept in the exhibition to highlight the practice of “playing Indian” in our society.

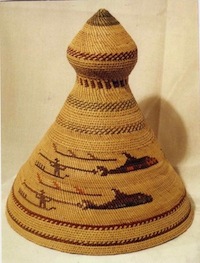

Polychrome twined Maquinna whaler’s hat with whaling scenes by Jessie Webster, Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), beargrass and cedar, 11”h x 9.5” in diameter at the base (circa 1975). Collection of E. J. Guarino

More recently, it was brought to my attention that a hat in my collection that had been designated as Makah circa 1900 was, in fact, Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) and created much later than previously thought. Shortly after the hat was featured in “HEAD TRiP: Collecting Native Hats” in November 2013, I received an Email from Stephen Lazarus, owner of Galerie Le Cedre Rouge/The Red Cedar Gallery, explaining that he was positive from the photo in my article that the piece was an onion domed Maquinna hat made by Jessie Webster circa 1975. Such hats are based on historic examples and take their name from Chief Maquinna who was drawn wearing such a hat by a member of the Juan de Fuca expedition when it reached Vancouver Island, British Columbia in 1792.

Although I was grateful to receive this information, I was also shocked. I had purchased the hat from a reputable gallery. The original receipt, still in my possession, states, “Makah whalers hat c. 1900.” In spite of having acquired the piece from a highly respected gallery, the information I was given was incorrect. Unfortunately, such errors do occur, though not frequently. Galleries make every effort to give their clients correct information. However, even with the best intentions, mistakes are sometimes made.

Obviously, the quest for that special work of art is what excites collectors most. However, getting information about each piece is essential. Collecting artworks is the fun part of the process, while the gathering of facts about each one is the work. For the serious collector, both aspects of acquiring art must be regarded as indispensable. Ferreting out information on a new piece is actually quite exciting. Doing so, I have often felt like some sort of “art detective.” True collecting is not just about acquiring a new trophy or object d’art; it should also be a pursuit of knowledge.