Collector's Corner

FACES: Portraiture in Contemporary Native American Works on Paper

When most people think of Native American art, they probably don’t think of portraiture. Nonetheless, it does exist. The people represented are often anonymous, but there is a large and growing body of work in which the subjects are identified. The purpose for creating portraits and self-portraits is to preserve the image of a particular person for the future and to reveal some aspect of the sitter’s character and personality. Usually, portraits and self-portraits are not simply a documentation of what a person looked like at a given period in time. Artists seek to capture the essence of their subjects. Some create a continuing series of portraits of a particular person or of themselves in an attempt to show how the subject has changed over time. Other artists use portraiture to record images of beloved family members, friends, prominent members of society, fellow artists, or writers they admire.

Choctaw Irish Relationship 8 by Sarah Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, bamboo paper, rice paper, inkjet print, wax tape, 22” x 30” (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Sarah Sense often creates works that are an exploration of her ancestry. Grandmother’s Stories is the umbrella title that includes the Choctaw Irish Relationship Series, the Doolough Trail Series, and Her Story, Our Legacy, a mural-size piece the artist created on-site at the Tulsa Hardesty Arts Center in 2015. The Choctaw Irish Relationship Series was inspired by the stories of Sense’s Choctaw grandmother. One of the stories was titled “The Choctaw Irish Relation.” Incorporated into the series are the words of her grandmother rewritten by the artist. For Sense, doing so was a way of keeping her beloved grandmother Chillie and her stories alive. Of the sixteen works in the Choctaw Irish Relationship Series, Choctaw Irish Relationship 8 is one of two that contain a portrait. It is an image of her great-grandfather Osborn Leonardo Blanche who was Choctaw. The inclusion of her great-grandfather in the series was a way of honoring him. In her statement about the piece, the artist wrote the following:

“This is my Great-Grandfather, who is Choctaw. My Grandma was very proud of him and his work for the Tribal Courts. He spoke all five languages of the civilized tribes of Oklahoma, English, and Spanish. I was hesitant about using the portrait in the work, but I love this image of him. This is two layers of rice paper, which gives the effect of water over his face; rather than layering in photoshop, these are layers of wax and rice paper for the transparent effect. On the left side of the image is the Chitimacha weave and the simple Choctaw diagonal weave comes through at the bottom, where I have cut away strips from the Chitimacha weave to expose the Choctaw. For me, this has a lot to do with me making work about my Choctaw ancestry, which is not necessarily my culture, but it is my Grandmother’s.”

Does Water Have Memory? by Sarah Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, photogravure and CMY lithograph, 10/25, woven and laser etching over the entire piece, archival paper, 19″ x 15″ (2017). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The artist once again used an image of her great-grandfather in Does Water Have Memory? According to the artist, “The portrait is photogravure and the sunset is a CMY lithograph and then woven and finally laser etching over the entire piece.” The woven section of the piece shows a sunset. Sense added, “The sunset is the Chitimacha land where we have burial grounds, very beautiful place.” Unlike the portrait in Choctaw Irish Relationship 8, nothing obscures our view of Mr. Blanche in Does Water Have Memory? By incorporating her great-grandfather’s likeness into her art, Sarah Sense has not only memorialized him but has also immortalized him.

Choctaw Bond Family IIII by Linda Lomahaftewa, Hopi-Choctaw, monotype, chine-collé, 11.5“ x 8.5” (circa 2010 – 2012). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Linda Lomahaftewa’s Choctaw Bond Family IIII is a family portrait which incorporates a photograph of the artist’s Choctaw grandfather and his family into the piece. The two seated figures in the image are the artist’s great-grandmother and great-grandfather. Standing behind them are the artist’s grandmother and her two brothers. Choctaw Bond Family IIII is a monotype in which the artist employed chine-collé, a special printmaking technique that refers

to transferring paper or other materials to a backing sheet. Linda Lomahaftewa made a photocopy of an old family photograph and collaged it onto the print, which features a traditional Choctaw design. According to the artist, Choctaw Bond Family IIII was created as a way to honor the Choctaw side of her family. Although it was an experiment, it turned out so well that she eventually created a number of similar works.

Legacy by Chris Pappan, Kaw, Osage, Cheyenne River Sioux, pencil/graphite, gold leaf, map collage, inkjet, acrylic on 1871 Chicago jewelers ledger; Image: 15”h x 10”w, framed: 26.75”h x 22.75”w (2018). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Sometimes the subject of a portrait is anonymous. His or her identity may have been lost to history and the artist may not know the name of the person whose image he is recording. This is the case with Legacy by Chris Pappan. Although the artist has tried to find out the identity of the person whose image he used in Legacy, he has been unable to find any information on him. “Sometimes,” Pappan stated, “I try to keep records of folk’s names (if available) sometimes not. But what I find frustrating is you can’t always rely on sources to give accurate info either.”

Like the majority of Chris Pappan’s work, Legacy is a mixed media piece, which employs collage and pencil work on ledger paper, in this case from 1871. The use of antique ledger paper references the Plains Indian ledger drawings that were created while Native American warriors were imprisoned. As soon as Native people had access to paper they began using it as medium for artistic expression.

Legacy presents a subject wearing a mixture of EuroAmerican and Native dress – a hat and jacket, a traditional hairstyle and a hair pipe necklace. In addition, the man holds a gun, which rests comfortably in the crook of his arm. He has a calm, determined look. Clearly, he is not someone to be trifled with. There is a line of buffalo above his head and another at his waist, which appear to move from left to right. Behind his shoulders is a smaller line of coyotes, which seems to move from right to left. This creates tension in the piece. These animals also function symbolically, the buffalo representing power as well as loss, since they were almost wiped out, and the coyote suggests cunning and survival. Behind the figure is a large gold leafed area in the shape of a half circle, which looks very much like a halo and imparts a tone of dignity and sacredness to the image.

Pursuit of Civilization #5 by Bobby C. Martin, Muscogee (Creek), photo etching, artist’s proof, 11”w x 14.75h” (2014). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Bobby C. Martin created Pursuit of Civilization #5 for Re-Riding History: From the Southern Plains to the Matanzas Bay, a traveling exhibition commissioned by the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum at Flagler College. Artists were asked to create an original work on paper that in some way responded to the imprisonment of Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho, and Caddo leaders at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. By order of the United States Department of War, seventy-two Native American men were held captive from 1875 – 1878. Martin chose to respond not directly to the prisoners’ time at Fort Marion, but to the period immediately after their release by focusing on one prisoner named Koba (Wild Horse) who was also a ledger artist. Koba eventually went to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania and learned to read and write English. “It is from one of his pages of carefully practiced cursive writing lessons that I selected to use as the foundation for my artwork,” the artist stated. “The piece, using a photo-etching process,” Martin continued, “combines an image from my own family’s past, a young man who attended Dwight Indian Training School in Oklahoma in the early 20th century. Many of my relatives attended various Indian schools, so I became very interested in Koba’s experiences and his connection to the formation of schools created to give our ancestors a ‘proper education.’”

Martin’s grandmother, Mabel Carr, attended the Dwight School, from around 1917 to 1919. The only thing that survived her time there were some photo postcards of the sports teams and a picture of a handsome mystery man.

Over the past twenty years, the artist has created works using the image of this unknown Native man in various media—paintings, lithographs, photo etchings, encaustic works—but he has yet to identify him. The figure in the photograph remains a mystery, one that Martin continues to investigate, but so far without results. “. . . we’ll never know exactly why my Granny only saved his photo and not other classmates,” Martin stated. “It’s a mystery that makes for interesting family stories.” Nonetheless, the “mystery man,” as the artist refers to

him is a powerful image of a Native American man employed in artwork by a contemporary Native American artist.

Granny Herron by Bobby C. Martin, Muscogee (Creek), drawing and gold leaf on mulberry paper mounted on panel with oil and gold pigment, 40” x 28” (2019). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Granny Herron is one of the portraits that Bobby C. Martin created for Altars of Reconciliation, an exhibit at at AHHA/Hardesty Arts Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The work is a drawing that the artist printed onto Japanese mulberry paper and then mounted onto a wood panel with the addition of a gold leaf background and edges and color borders done in oil paint. “For this particular show,” the artist stated, “I wanted the works to resemble the look of historic religious icon paintings . . . . These people are my spiritual icons not icons that I worship, but ones that I remember fondly as faithfully looking out for my spiritual well-being, whether I knew it or not. My goal is to follow their pattern for my own children and grandchildren.”

Mabel (Carr) Herron was the Bobby C. Martin’s maternal grandmother. A full-blooded Muscogee (Creek) citizen, she was born in Indian Territory in 1896 near Checotah in the heart of the Creek Nation. As a young child, she was registered on the infamous Dawes rolls and given a land allotment, land on which many of her descendants still live. She married Ransom Wesley (R.W.) Herron, a white horse trader and watermelon salesman whose family had moved from Tennessee shortly after Oklahoma statehood in 1907. They made their home on Mabel’s allotment land and raised six children, the fifth of whom was the artist’s mother, Bonnie.

Mable Herron became a matriarch of the Deep Fork Hillabee Indian Baptist Church where her father, the artist’s great grandfather, Willie Carr, was the pastor. Church services were sung and preached in the Mvskoke language. According to Bobby C. Martin, his grandmother, whom he called Granny, was always at the center of it all and he added, “I also remember summertime visits to the old home place. . . . She passed away when I was fifteen. Although I didn’t realize it then, her gentle guidance and training during those summers spent at the old home place planted the spiritual seeds that eventually took root in my own transformation into a follower of Jesus Christ much later in adulthood.

In Granny Herron, it was his grandmother’s gentle guidance and grandmotherly protection that Bobby C. Martin wanted to honor. “These folks,” he wrote in an Email correspondence, “are not only my physical but also spiritual ancestors.” For Altars of Reconciliation the artist stated that he “. . . created a ‘memorial wall’ to honor their influence on my spiritual formation—but also in order that others might be reminded of their own family’s roles in their lives.”

Memorial Song Series, Sleeping Bear, Sioux by Shan Goshorn, Eastern Band Cherokee, Arches watercolor paper splints printed with archival inks, acrylic paint, app. 4“ x 4“ x 4.5” (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino

“When I was doing research among . . . historical photographs . . . I was awed by the clear, honest studio portraits commissioned by the photographer Frank Rhinehart,” Shan Goshorn wrote. The photographs were taken during the 1898 Indian Congress in Omaha, Nebraska. “. . . this gathering,” Goshorn added, “attracted over 500 members of 35 different tribes. Viewing these photos led me to wonder about the course and adaptability of these Indian men and women who were curious enough about their quickly changing world to travel to the event. These portraits are unique in that they are a non-exotifying collection, simply recording the participants as they were without the glamor of special backgrounds or added props.”

Part of the artist’s Memorial Song Series, Sleeping Bear, Sioux memorializes Lower Brulé Sioux leader, Sleeping Bear in a work that employs a traditional Eastern Band Cherokee single-weave pattern known as Chief’s Heart. The piece incorporates a photographic portrait of Sleeping Bear by Frank Rhinehart taken in 1898 and includes the words of a memorial song woven into the interior: “We remember your sacrifices. You will not be forgotten.”

Although they are most often referred to as baskets, perhaps the pieces Shan Goshorn created would better be described as soft sculptures. Where baskets were once used to store and carry various items – particularly food – Shan Goshorn’s creations hold and convey ideas – food for thought. In Memorial Song, Sleeping Bear, Sioux, the modernist basket becomes a container which holds the memory of Sleeping Bear.

Portrait of Clayton Brascoupe by Eliza Naranjo Morse, Santa Clara Pueblo, colored pencil and pen, 4“w x “ 4.25”h (2010). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Clayton Brascoupe may not be known to many people, but he is extremely important to Native Communities. Although Brascoupe is Mohawk and Anishnaabe and was born on the Tuscarora Iroquois reservation in New York State, he has lived at Tesuque Pueblo for forty years and is one of the founders of the Traditional Native American Farmers Association (TNAFA). Brascoupe and his wife, who is of Tesuque heritage, became concerned because so few young people were engaged in farming. They also saw a rise in social and medical problems – drug and alcohol abuse, domestic violence, obesity, and diabetes – things that did not exist when the entire community had been involved in food production. In addition, the Brascoupe’s and others noted that there was a loss of seed diversity and that the amount and quality of water available to Native Communities was in jeopardy. The act of producing one’s own food was seen as a political act, which asserted sovereignty, self-determination, and self-sufficiency. Eliza Naranjo Morse stated, “This man has spent most of his life supporting permaculture in Native Communities through sharing information. The first time I gathered food from a field was with him.” She went on to add, “. . . that man is a visionary.”

Self 00 by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint/etching, 6/10, paper size: 8”w x 11.5”h; image size: 1.5”w x 2.5”h (2000). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Self 00 (Detail)

Often artists create self-portraits. Some are representational, showing how the artist looked at a particular time in his or her life, but others are often symbolic, or even surrealistic. Among Rick Bartow’s drypoint etchings there are quite a number of self-portraits.

Self 00 shows the artist wearing his signature eyeglasses as well as a hairstyle that he had throughout much of his career. The hair is thinning and the face is lined and a bit weary. The fact that the glasses are, in essence, blackened out suggests that Bartow was concentrating on looking inward rather than outward.

Headband by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, hand colored drypoint/etching, A/P, 9”w x 11.5”h (2001). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Produced the year after Self 00, Headband is another Bartow self-portrait. In this work, the artist presents an image of himself that is in sharp contrast to the earlier print. In it Bartow portrays himself wearing a bandana that suggests the Stars and Stripes, which is a reference to the time he spent serving in the Viet Nam War. In Headband, the artist’s vision is not obscured. His eyes are clearly visible through his eyeglasses. Headband and Self 00 suggest two aspects of the artist’s nature: at times he was introspective, but he also engaged with the world and was willing to face life head on. Over the years Rick Bartow had to deal with his Viet Nam War experiences, the loss of his wife to breast cancer as well as other personal problems. These struggles informed his art.

Seii by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, 18/20, 12” x 10” (1998). Photo courtesy of the Froelick Gallery.

Seii by Rick Bartow is a portrait of artist, master printer, and gallery owner Seiichi (Seii) Hiroshima. To produce his drypoint prints, Rick Bartow worked closely with Seii. According to Charles Froelick, owner of the Froelick Gallery in Portland, OR, “Hiroshima is the print maker (master printer) who editioned Rick’s drypoints. . . . Rick and Seii called their collaborative press ‘Moon and Dog Press.’ Their chop is found on nearly all of the prints they made together – a dog jumping over a moon and a backwards ‘R’.” Wilder Schmaltz, Assistant Director of the Froelick Gallery, added “Seiichi Hiroshima was formerly the proprietor of Azabu Kasumicho Gallery in Tokyo.” Hiroshima hosted several exhibits of Bartow’s work at his gallery. The artistic collaboration of Bartow and Hiroshima began in 1991. Bartow would scratch images onto plexiglass and metal, then mail them to Japan where Seiichi Hiroshima printed each edition on paper and send back the final images. Over the years the two men worked together both in Japan and Oregon, producing drypoints and monotypes.

Gustav Mahler by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, hand-colored drypoint etching, P/P, 10” x 6.5” (2010). Photo courtesy of the Froelick Gallery.

Since Mahler died in 1911, Bartow obviously did not create his likeness from life, but was inspired to do so by his admiration for the composer. Often in portraiture, the sitter is either looking directly at the viewer or facing left. Bartow chose to create his portrait with Mahler facing right, in sharp profile. The addition of hand-coloring brings the image to life, particularly in its emphasis of the composer’s rather large nose. Mahler, who composed ten symphonies as well as other works, created music on a grand scale. Like Rick Bartow, he wanted to express his view of the human condition through the lens of his own life experiences. Mahler once stated, “My symphonies represent the contents of my entire life.” It is not surprising, then, that Bartow would admire Gustav Mahler so much that he would want to create a a portrait of him.

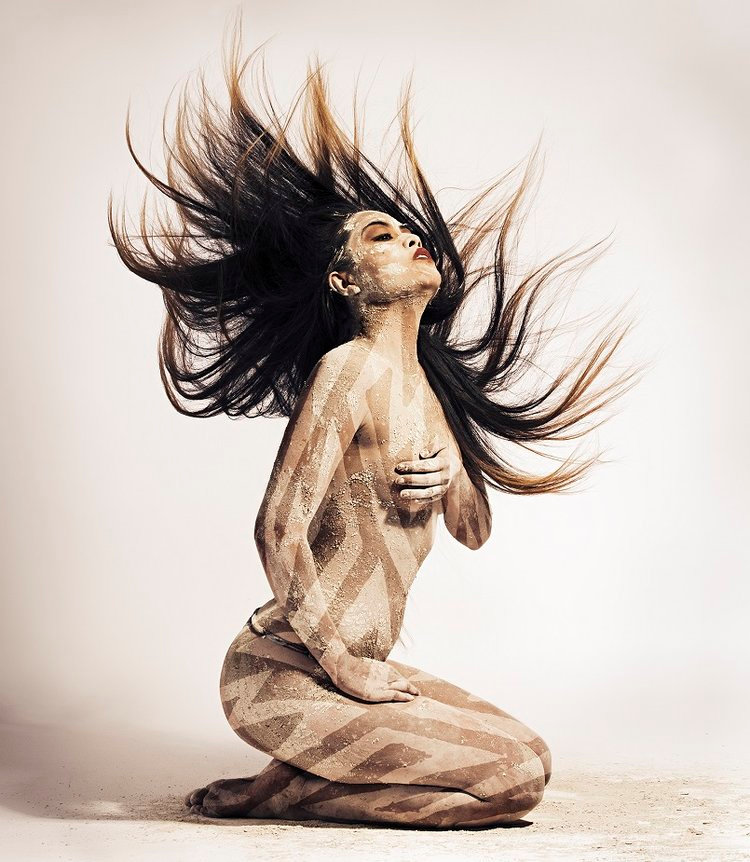

Kaa by Cara Romero, Chemehuevi, archival pigment photograph, 49 5/8” x 43 1/4” x 11 1/2” (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Although she comes from a rural reservation, as a contemporary Indigenous woman, Cara Romero, like most Americans, is surrounded by pop culture. Her models are usually family members or friends and, although her photographs focus on Indigenous themes and subjects, they have a universal quality that communicates across cultures. As an artist, Romero is concerned with our shared human condition but expresses her unique perspective through her depictions of present-day Native people.

Native Americans, particularly women, have been stereotyped in numerous ways in paintings, sculpture, literature, theater, movies, and TV. Females have been romanticized and exoticized, usually portrayed as alluring while at the same time passive and submissive. Native people – both male and female – have been portrayed in the media and mainstream culture as violent and overly sexual. It is an image that is, for many, both frightening and titillating. Until fairly recently such stereotypes went unchallenged.

One of the artist’s most striking works is Kaa, a portrait of Pueblo ceramic artist Kaa Folwell. The subject comes from a long line of Pueblo ceramic artists so it was fitting that for this photograph Kaa was painted in clay and a photo of a Mesa Verde vessel was overlaid on her body. According to the artist, she shot the photo at 1/8, 000th of a second in order to capture the subject’s hair the way she did. Romero felt that doing so suggested the unpredictable nature of clay. She also wanted to evoke the moment in the firing process when the clay chemically transforms.

Historically, nudity is rare in Indigenous art. For that reason, the photograph is, at once, unexpected and a bit shocking, although the image is discreet and tasteful.

Jenna, by Cara Romero, Chemehuevi, archival pigment print, edition of 5, 37 3/4” x 37 3/4” x 11 1/2” (2016). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Jenna is a portrait of Jenna Osuna, a mixed martial arts competitor from New Mexico. This striking photograph presents the image of a woman wearing boxing gloves and posed in a stance suggesting that she is ready to fight. The powerful image created by Cara Romero offers a counter-narrative to the one usually offered regarding Native women. Jenna is neither passive nor submissive. The work is a visual ode to female strength.

For much of the 20th century and well into the 21st, representational art has often been ignored and even derided in favor of abstraction. The work of artists who produce portraits and other figurative art is frequently disregarded. However, portraiture has been an important part of the artistic canon for over two thousand years and has only recently fallen out of fashion. A large number of contemporary Native artists create representational art and many produce portraits of historical figures, beloved family members, friends, prominent Native Americans, artists, writers, and composers whose work they appreciate, as well as self-portraits. Although portraits by contemporary Native American artists are often done on canvas or paper, they are not confined to these media and have been produced in sculpture, beadwork, and ceramics as well. Most people are not aware of Native American portraiture. It is a subject that is rarely addressed and when portraits of Native Americans are exhibited they are usually works created by non-Native artists. This is unfortunate, but as more Native American artists produce portraits additional collectors and curators will become aware of their existence and significance. One of the most important aspects of contemporary Native American portraiture is that Native artists are taking control of the narrative. We are seeing Indigenous people through a Native lens rather than filtered through one that is non-Native as has been the case for five hundred years.