King Galleries Blog

“Revival Rising” Ohkay Owingeh Pottery 1930s-60s

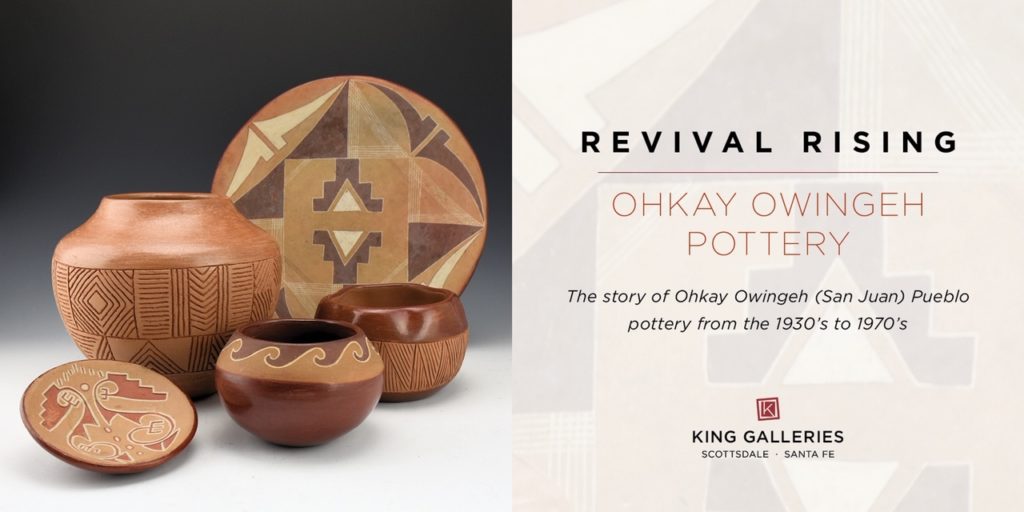

“Revival Rising” Ohkay Owingeh Pottery

This show features Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo (formerly San Juan Pueblo) pottery from 1930s-1960s. Charles King has collected the pottery for this show for more than a decade. Why so long? Many of these potters were not very prolific. Also, finding pieces which were not damaged over nearly 70 years has proved equally as difficult. The goal in putting together this show has been to find signed work, interesting in shape and design and in the best condition possible. While there has been a focus on many of the other Pueblos and their rich history in clay, there has been very little academic research done on this formative period of Ohkay Owingeh revival pottery. This show is one of the first to present a nearly comprehensive collection of Ohkay Owingeh pottery reflecting on the various revival potters as well as all the different styles created during this formative period. There are well over 50 pieces from the years 1931 to the 1970s. Nearly all the pieces are signed and include work by most of the “Original Eight” revival potters. It is a unique opportunity to learn more about this distinctive pottery and see them in person.

Brief Background of Ohkay Owingeh Pottery 1930-60s

Although San Juan Pueblo was famous for its pottery in the late 1800s. However, by 1900 pottery had nearly died out at the pueblo as an art form, even as it was flourishing in nearby Santa Clara and San Ildefonso. By the 1910 US census nobody identified as a potter at the Pueblo, while many did at nearby San Ildefonso and Santa Clara Pueblos. In 1930 only two potters, Crucita Trujilo and Juanita Torres identified themselves as potters. By 1940, however, nine years after the revival, there were 59 potters at San Juan Pueblo.

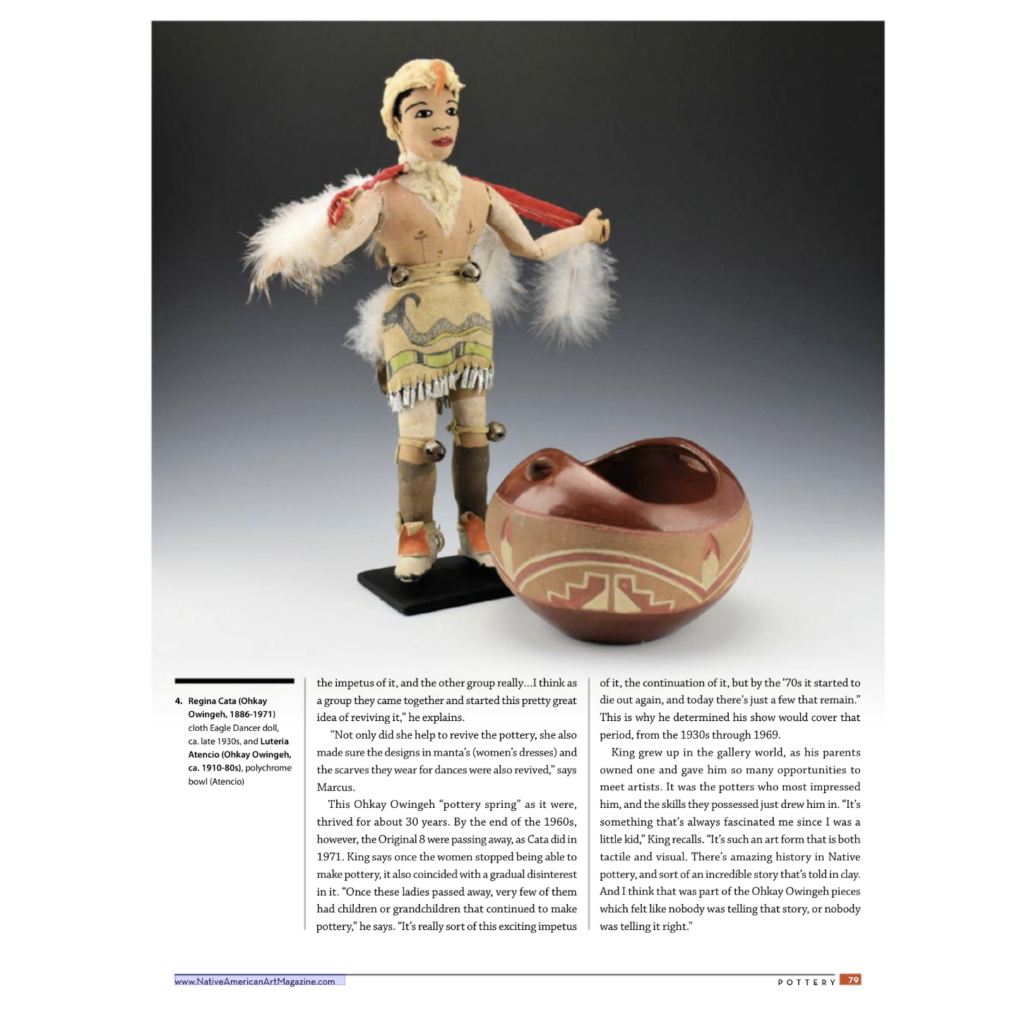

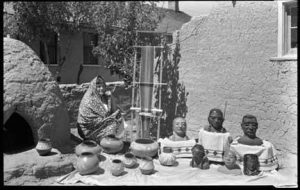

It was in 1930 that a revival began at the Pueblo. Regina Cata (who was Spanish and married to Eulogio Cata of San Juan Pueblo) was an employee at the San Juan Day School. She was the wife of Eulogio Cata, who was a Governor of San Juan Pueblo. She encouraged the formation of an art club to make mantas, ceremonial regalia, and household items embroidered by local Pueblo women. The lessons learned in the embroidery techniques and designs created in this club would later appear as inspiration in the incised style of pottery in the revival.

The Eight Revival Potters of 1930-1

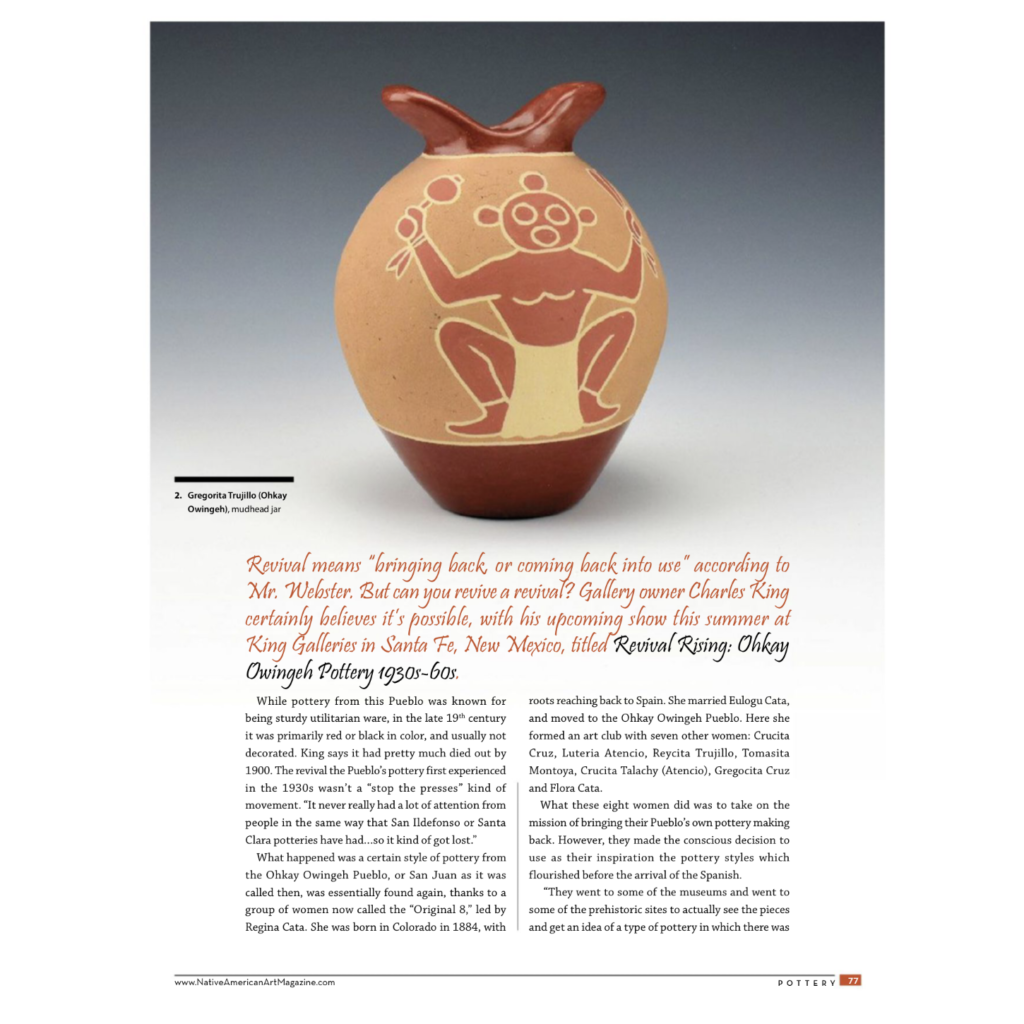

It was a group of Eight Women who began this San Juan pottery revival. Regina Cata, Crucita Cruz, Luteria Atencio, Reyecita Trujillo, Tomasita Montoya, Crucita Talachy (Atencio), Gregorita Cruz and Crucita Trujillo. Most likely they had seen the success of the pottery revivals at San Ildefonso and Santa Clara Pueblos in the 1920s. Their initial idea was to revive a pre-Spanish style of pottery. They wanted to create a style which did not replicate the styles from other pueblos, but distinctly their own and distinctly “San Juan”. They took trips to Poge (the Ohkay Owingeh ancestral village) and also to the Museum of New Mexico to find inspiration.

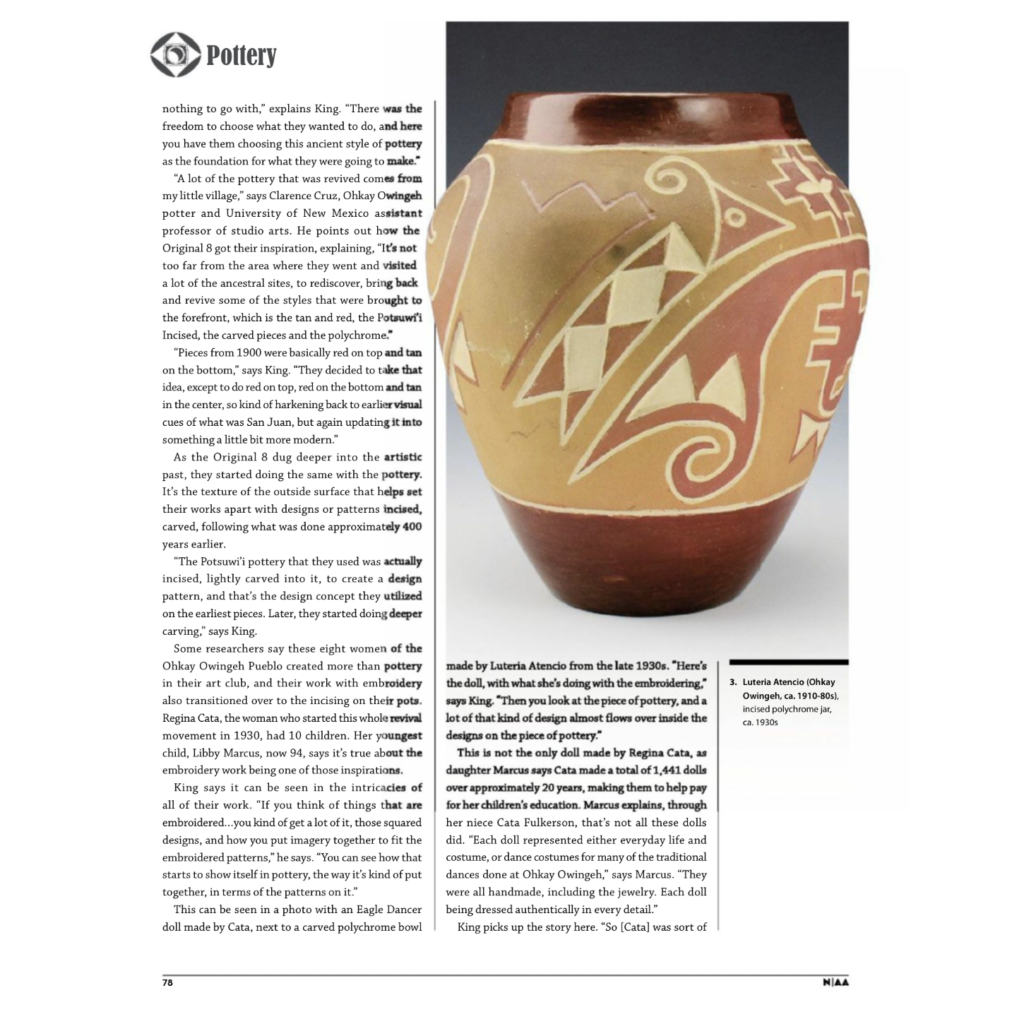

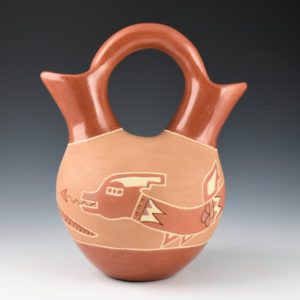

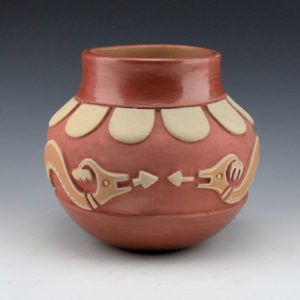

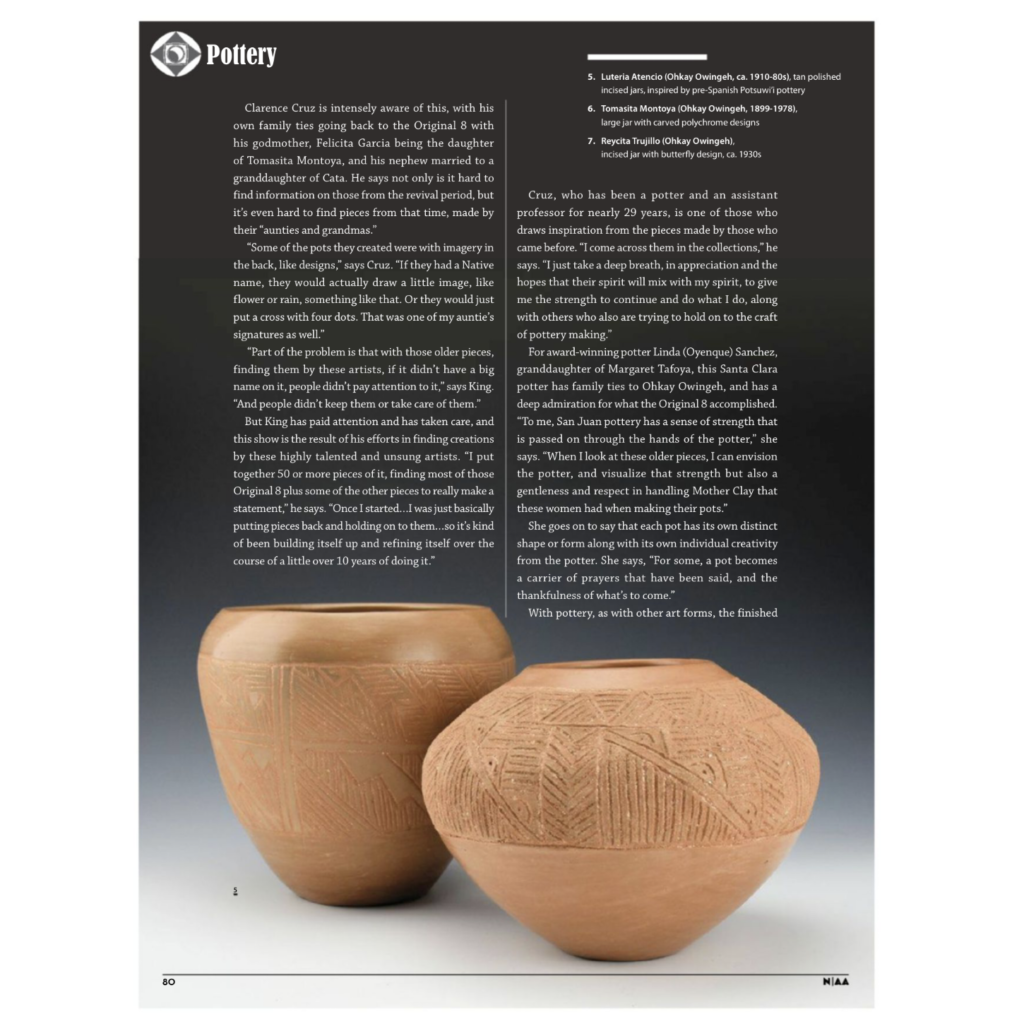

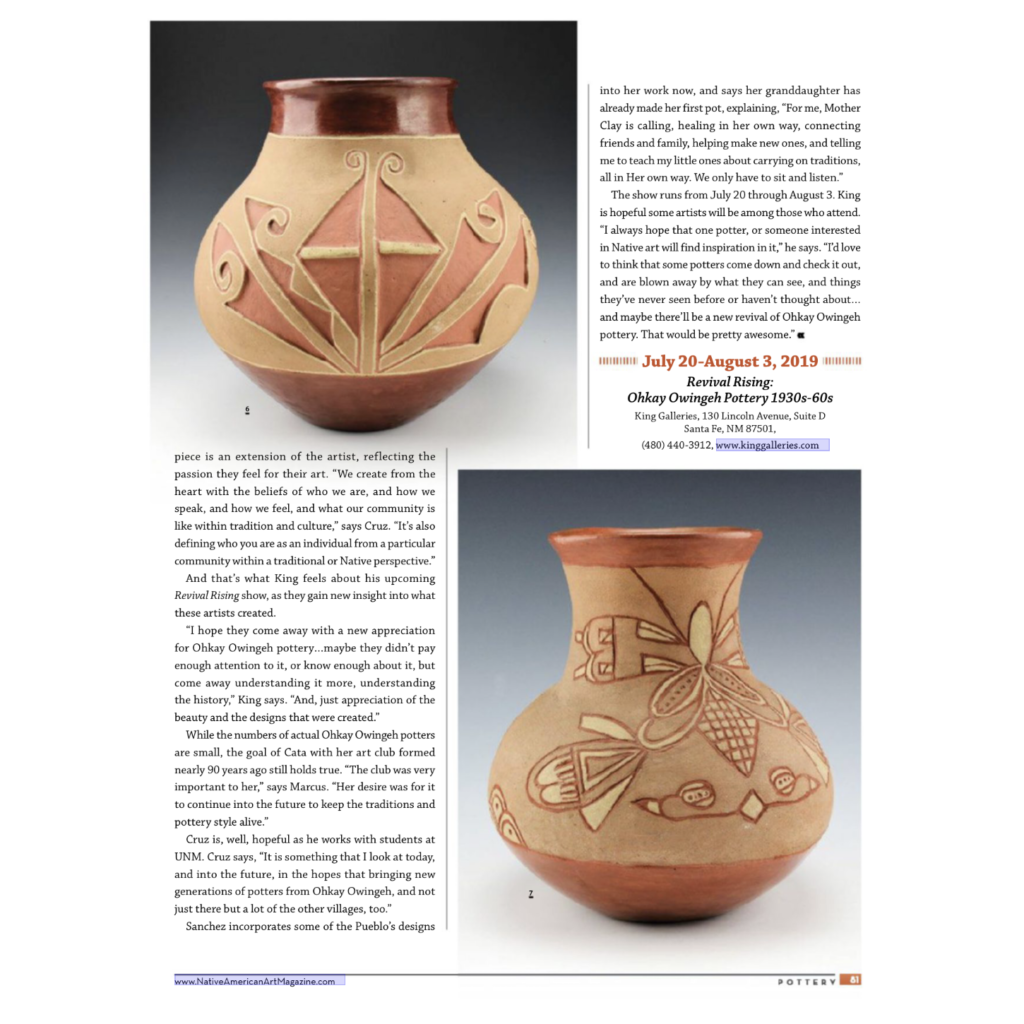

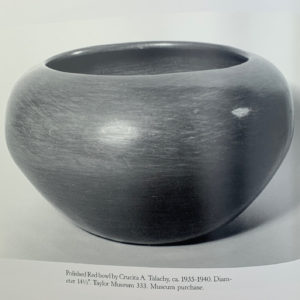

The women decided on a style of pre-contact pottery known as “Potsuwi’i”. It was an incised style of pottery made from the 1450s to the 1500s and had a gray coloration. Instead of keeping the gray coloration, the women first began all tan polished pieces and then decided to utilize the early San Juan red and tan coloration, with the colors reversed. There rim or neck of the piece would be polished red. The central band would be left matte or unpolished and then incised and slipped with micaceous clay to highlight the designs. By 1931 they began making and selling this new style of pottery.

While Cata may have been the instigator of this revival, it was the other seven woman who met the challenge to create something new. There was incredible freedom, bordering on exuberance in the “newness” of their work, in both forms and style.

The incised style quickly caught on among buyers and became synonymous with San Juan Pueblo pottery in the 1930s. In 1935, more deeply carved designs began to appear on the pottery surface. Again, the coloration was influenced by the pre-1900 red and tan colorations. The designs were inspired by San Juan traditional imagery. The detail and symmetry in much of the design work reflect the earlier influence of the embroidery designs in the art club.

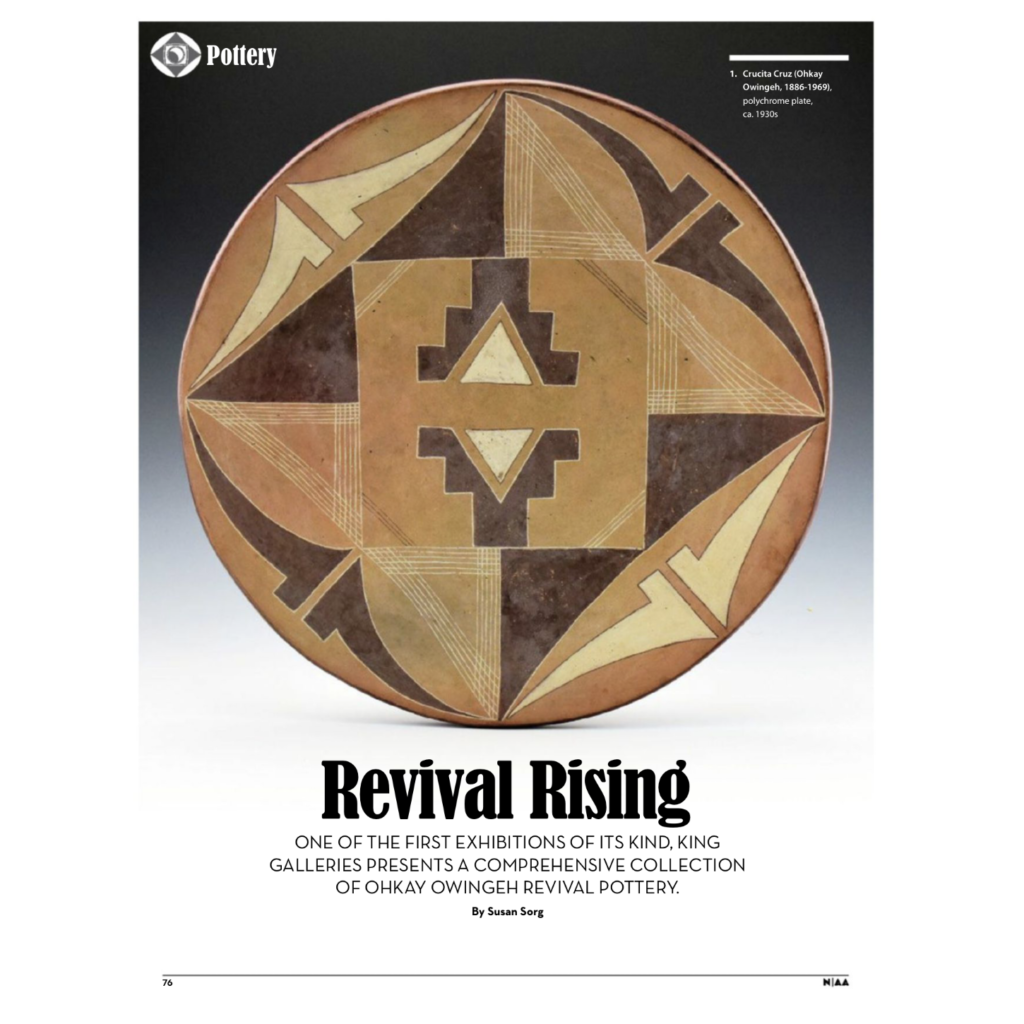

A few potters, such as Crucita Cruz, added an additional painted polychrome style in the early 1930s. There was still the polished red, white, and tan clay colorations. However, she also added a “purple” or mauve clay slip which was popular at the time at the Pueblos as an additional highlight.

By the 1940s there were more potters making work at the Pueblo. The level of creativity and innovation, however, was not as refined as the creative naissance of the 1930s. By the 1960s, many of the “Original Eight” had either passed away or were no longer making pottery. However, they continued to leave an important legacy. In 1968 Luteria Atencio and Geronima Montoya founded the O’ke Oweenge Crafts Cooperative. Tomasita Montoya lived the longest of the original group, passing away in 1978 and becoming one of the most prolific of the potters of her time.

San Juan Revival: Phase Two

In the late 1960s to 1970s, much as with other areas of Native art and in Pueblo pottery, there was a renewed outside interest in the arts by collectors. Martina Aguino and her son Diego Aguino, Mary Ester Archuleta, Felicita Garcia, Dominguita Sisneros, Rosita de Herrera, Myrtle Cata and others were among those who refined the early revival style of both incised and carved polychrome pottery to create more complex new works. They challenged the concepts of the pottery as craft and began a refining process which attempted to move the style towards fine art. However, for various reasons, these potters either stopped making pottery by the 1980s or continue to make very little pottery.

Today, very few potters remain active at Ohkay Owingeh. The dynamic story of this pottery revival and its impact on Pueblo pottery has barely been touched upon by researchers and academics. This is a unique opportunity to take a bold step forward to document and showcase these exceptional potters and celebrate their genius and initiative which quickly transformed from “revival” to a new style of pottery in both design and form.

The “Original Eight” Resolved: The Crucita Trujillo Question

There has been confusion over the years concerning the “Original Eight”. Numerous texts and writings have listed 7 potters with a mysterious “unknown eighth”. It would seem that this confusion centers around one artist name but consists of two separate people. The question of Crucita Trujillo is actually a confusion over two women with nearly the same name. There is Crucita Trujillo Cruz (1886-1969) and Crucita Abeyta Trujillo (1887-?). They are born at nearly the same time and ended up with the same name. It would seem that most early writers must have thought the name was a duplication in their lists. However, they were both making pottery in the 1930s and their styles are very distinctive and different. There is documentation in articles from the time (El Palacio, etc) where Crucita Trujillo Cruz is named as part of the “Original Eight”. Other articles include Crucita Abeya Trujillo. The reality seems to be, until research proves otherwise, that both were part of the “Original Eight” and it has been a long term error of similarity of names.

Ohkay Owingeh Revival Pottery Condition and Scarcity issues

One of the great difficulties in collecting Ohkay Owingeh signed pottery from the 1930s is the condition. The pieces were well made but overall, have not always been well cared for over the years. While pottery from other pueblos has commanded significantly higher values, the pottery from Ohkay Oweingeh has been more “folk art” in style and similarly priced. Maybe this has influenced the sparsity of research into the artists and the art form. However, it is much more difficult to find pieces in exceptional condition from this period. While many of these potters were prolific at the time, there is very little work of theirs around today. Why? They are names which were not recognized, and pieces were neither donated to museums or kept by collectors. Finding work by the “Original Eight” and other potters from this period is difficult at best. While Tomasita Montoya was the most prolific, even her early work is more scarce and there are some of these potters whose work only appears over the course of decades, not years! We hope that by providing more information about these amazing artists, collectors and museums will take a fresh look at their creativity and innovative shapes and designs.

From San Juan Pueblo to Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo

San Juan de los Caballeros, as it was christened by the Spaniards, or better known as San Juan Pueblo has become Ohkay Owingeh (pronounced O-keh o-WEENG-eh). This translates to “Place of the Strong People.” San Juan Pueblo is no more. The pueblo’s tribal council restored the community’s traditional name in September 2005.

Click here to see pottery featured in “Revival Rising”.

Timeline 1930’s Revival

Below is a brief visual timeline of the styles involved in Ohkay Owingeh pottery revival

Potsuwi’I Incised: Tan 1930-1

Potsuwi’I Incised: Red and Tan 1931

Incised Red/White/Tan with polished Rim 1932

Carved Designs 1938

Second Phase Revival 1970’s

The Original Eight

2. Luteria Atencio (1891-1982)

3. Crucita Talacy Atencio (1913-1996)

4. Crucita Trujillo Cruz (1886-1969)

5. Crucita Abeyta Trujillo (1887-?)

6. Reyecita Aguino Trujillo (1900-1944)

7. Tomasita Montoya (1889-1978)

No Pottery Found

Other San Juan Potters 1940 – 70

Second Phase Revival: 1970’s

Archuleta, Mary Ester (b.1942)

Dominguita Sisneros Naranjo (b. 1942)

Special thanks for the additional help in researching the potters and pottery. Also Linda Tafoya-Sanchez and Anthony Trujillo for their insights into Ohkay Owingeh pottery.

“Revival Rising” Article from Native Art Magazine, June/July 2019