Collector's Corner

FAMILY VALUES: Sarah Sense’s Grandmother’s Stories Series

Collectors become aware of artworks they wish to acquire in a variety of ways. From May 1 through July 5, 2015, the Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa Hardesty Arts Center presented INTERTWINED, STORIES OF SPLINTERED PASTS: Shan Goshorn & Sarah Sense. Although I could not see the exhibit in person, the artists gifted me with a catalogue. Through it I became aware of Sarah Sense’s Grandmother’s Stories, comprised of the Choctaw Irish Relationship series (sixteen works) and the Doolough Trail Series (twelve works). Grandmother’s Stories is the umbrella title that includes the Choctaw Irish Relationship series and the Doolough Trail series and also includes Her Story, Our Legacy, the large piece that the artist made on-site in Tulsa. My eye was immediately drawn to a number of works and I Emailed the artist to ascertain if it would be possible to acquire them. After a series of Emails in which Ms. Sense sent me images and factual information, I decided upon five pieces. Ever since, I have been contemplating why I chose these five works out of the twenty-eight images I saw. Although they are visually beautiful, they reference two devastating episodes in human history: the Great Hunger and the Trail of Tears.

Shortly after I met Sarah Sense she began traveling in Central and South America and, then, Southeast Asia. At the time, she assiduously avoided Europe because she had been there before and felt that it was not relevant to her work. However, the artist’s life, art, and travels began to merge when she traveled to England for an exhibit of her work and met her future husband. Realizing that she would be in Europe longer than she had expected, Sense began to cast about for subjects to research that would be pertinent to her work but, at first, come up with few ideas. Eventually, she remembered an old story that her Grandma Chillie had told her about the Choctaw Irish relationship and the Choctaw community gifting money to the Irish during the Irish famine in the 1840s.

At ninety-one, Sense’s Choctaw grandmother began to write about her family, her travels, her loves, and her disappointments. One of the stories, written in August 2014, was titled “The Choctaw Irish Relation.” Ironically, shortly before her grandmother’s death in 2015, the artist moved to Ireland. The text incorporated into the Choctaw Irish Relationship series are the words of her grandmother rewritten by the artist. For Sense, doing so was a way of keeping her beloved grandmother and her stories alive. Sense’s Grandmother Chillie was a nurse, storyteller, photographer, world traveler, writer, and basket collector. The Choctaw basket designs incorporated into her Grandmother’s Stories series are derived from the two baskets given to the artist by her grandmother; the Chitmacha patterns are based on a basket by John Paul Darden, one of the few living Chitimacha basket weavers.

Doolough Trail 5 by Sarah Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, bamboo paper, archival inkjet prints,metallic paper, 12″ x 14” (2014). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The Doolough Trail Series is a collection of landscapes from where the artist currently lives. According to Sense, “This series really is the beginning of my research and work on the Choctaw Irish Relationship.” The connection between the Choctaw and the Irish was forged in the mid-1800s. In March 1849, people in Louisburgh, Ireland were starving as a result of the failure of the potato crop. Believing that they would be given food if they walked ten miles to Delphi Lodge to speak to their landlord and the Council of Guardians, six hundred people – men, women, and children – made the journey in freezing weather only to be turned away. Many died on the way back on the shores of Doolough Lake. Many of the dead were discovered with grass in their mouth. An Gorta Mor – The Great Hunger – as it came to be known, is Ireland’s greatest tragedy. It is estimated that between 1845 and 1850 one million people died of starvation and another one million were forced to emigrate, mostly to the USA. When members of the Choctaw tribe learned of this catastrophe they raised $710.00 (approximately $20,000 today), which they donated to Irish famine relief Although this might not sound like a huge sum of money today, it must be remembered that the Choctaw were desperately poor themselves. They also gave corn and blankets. Eighteen years earlier, the Choctaw had been forced to leave their ancestral lands and made to march some five hundred miles to what was called Indian Territory and later became Oklahoma. It is estimated that nearly 17,000 Choctaws were removed to new lands. Along the way between 2,500 and 6,000 died from cold, hunger, disease, and exhaustion. In a show of gratitude and solidarity with the Choctaw, in 1992 a group of Irish walked the Trail of Tears, raising $710,000, that they donated to famine relief in Africa.

As a collector I was drawn to Doolough Trail 5 because of it’s visual beauty, which belies the tragedy that took place along it’s route one hundred and sixty seven years ago.

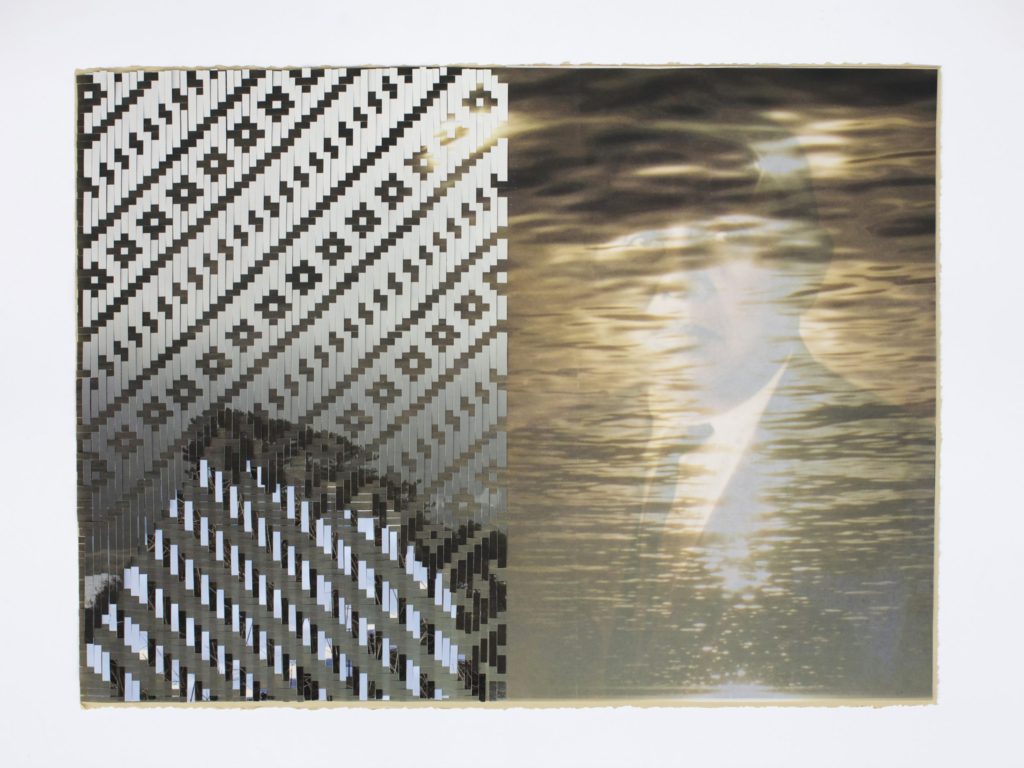

Doolough Trail 7 by Sarah Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, bamboo paper, archival inkjet prints, metallic paper, 12″ x 14” (2014). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Doolough Trail 7 portrays the same landscape as in Doolough Trail 5 but the color and strong imagery of the Native basketry weave of the seventh work in the series gives it both an ethereal and melancholic quality. The artist created the Doolough Trail series while she was living in Galway, Ireland and said that it “. . . changed my material methods for the series, Choctaw Irish Relationship. The story about the Choctaw’s gifting the money to the Irish is the story that I am trying to convey, the story that I am researching. And again it is the personal story that comes with the research – coming to Ireland for the research just after marrying my husband and then his finding a job in the lodge where we came for my research. Sometimes I think that I should be an author rather than a artist because I want to share my research and my experience of how I obtained it. But instead, I am trying to make a visual journey that imitates this research and personal experience.”

Choctaw Irish Relationship 3 by Sarah Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, bamboo paper, rice paper, pen and ink, inkjet print, wax, tape, 22″ x 30” (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino

I was immediately drawn to Choctaw Irish Relationship 3 because of its sad, nostalgic quality, which is relieved by the inclusion of Native American weaving patterns, and the road that seems to go on forever, especially since on it stands a lone cow. According to Sense,“This piece, . . . has landscapes from Ireland, but also includes a landscape from Montenegro. The image with the cow is from a drive that we took from Galway to the Cliffs of Moher. This was the first journey that we took in Ireland and on the journey we met a pub owner who suggested that we go up to Louisburgh to see an Irish Hunger memorial. The two images woven through the left and right are of Montenegro. We were in eastern Europe before traveling to Ireland. The text is my grandmother’s story about traveling titled ‘Trekking in Paradise.’ She had a huge influence on me. All the writing in this show [‘Intertwined’] is her words re-written by me. I re-wrote three stories of hers: ‘Choctaw Irish Relationship,’ ‘Personal History of Marriage, Disappointments, Divorces and Re-Marriage,’ and ‘Trekking in Paradise.’ These pieces speak of our journeys, family, marriage, searching for history, and my understanding the story. My grandma worked with me on this show until passing away in early March 2015.”

Choctaw Irish Relationship 3 as well as Choctaw Irish Relationship 7 and Choctaw Irish Relationship 8 were selected because each has an exquisite, otherworldly quality.

Choctaw Irish Relationship 7 by Sarah Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, bamboo paper, rice paper, collagraph print, inkjet print, wax, tape, 22” x 30” (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino

“Choctaw Irish Relationship 7 has a inkjet print on one side of rice paper and a collagraph print which I did by hand on the other side,” the artist explained. “I thought that the delicate contrast of whites on the backside of the print was much more beautiful, so the finished piece is the digital print facing down. The bamboo paper with inkjet prints is woven through the sides. The image is blades of grass, again a delicate depiction of a very common part of the landscape here in Ireland. This piece has two photos from Ireland. The simple angled weave that is repeated in a few of these pieces is from a basket that my grandmother gave me. This piece has the collagraph print of a Chitimacha weave printed on

the front, making it more visible than the other pieces that feature the collagraph.”

Choctaw Irish Relationship 8 by Sarah Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, bamboo paper, rice paper, inkjet print, wax tape, 22” x 30” (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino

One of the most intimate works in one of the artist’s most personal series, Choctaw Irish Relationship 8 is one of two pieces in the series that contains a portrait. “This is my Great-Grandfather, who is Choctaw,” the artist explained. “My Grandma was very proud of him and his work for the Tribal Courts. He spoke all five languages of the Civilized Tribes of Oklahoma, as well as English and Spanish. I was hesitant about using the portrait in the work, but I love this image of him. This is two layers of rice paper, which gives the effect of water over his face; rather than layering in photoshop, these are layers of wax and rice paper for the transparent effect. On the left side of the image is the Chitimacha weave and the the simple Choctaw diagonal weave comes through at the bottom, where I have cut away strips from the Chitimacha weave to expose the Choctaw. For me, this has a lot to do with me making work about my Choctaw ancestry, which is not necessarily my culture, but it is my Grandmother’s. The slight exposure of this is a mirror of my experience with coming to Oklahoma and making work about being Choctaw, by way of family, not experience.”

One of the pleasures of collecting the work of living artists is being able to ask them questions about their work and then documenting their responses. Often, artists don’t realize that what they say or write with regard to what they have created is very important in revealing their artistic process. Sarah Sense has been exemplary in providing me with information about the pieces I acquire from her. Perhaps it is because she knows that my collection will eventually be gifted to museums, a process I’ve already begun, and with each piece I also include all pertinent documentation. A major part of many donations is artists’ statements. As a collector, I was thrilled that Sense included such information as I was considering each piece in her Grandmother’s Stories series.