Collector's Corner

FILLING IN THE GAP: Collecting Early to Mid-Twentieth Century Native American Works on Paper

Recently, I came to the conclusion that, although I have ledger drawings from the 1800s and many contemporary Native American prints and drawings in my collection, it contains no Native works on paper from the early to mid-twentieth century. As a collector, it is important to me that, as much as possible, all areas of my collection reflect the depth and breath of Native creativity. It became unthinkable to me that more than half a century of Native works on paper were not represented in my collection. I couldn’t understand why I had not realized this omission earlier and became determined to remedy the problem as soon as possible.

Since I would be traveling to Santa Fe, I decided that I could easily begin to fill this gap in my collection and decided that a good place to start would be the Case Trading Post. I can honestly say that I have never visited the Case Trading Post without leaving with one or more incredible artworks, and that is not a bad thing. Located in the basement of the Wheelwright Museum, the Case Trading Post Museum Shop is a collector’s dream come true. It is filled with a diverse range of Native art at prices that are among the best in Santa Fe. Much of this excellence is due in large part to Ken Williams (Arapaho/Seneca), the Case Trading Post Manager who is also an award winning artist. Entering the trading post, the early 20th century wooden floors creaking delightfully under my feet, I spotted a small, framed work hanging on a beam that I immediately thought was interesting and asked to see it closer. It turned out to be a watercolor of a dancer by Patrick Swazo Hinds. Although I was unfamiliar with the artist, I felt that the work was beautifully and delicately rendered and decided to acquire it. Much to my surprise the notes I received with the piece indicated that the artist had created it when he was only nine years old.

Dancer by Patrick Swazo-Hinds, Tesuque, watercolor, 3.75” by 5.5” (circa 1938). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Dancer by Patrick Swazo-Hinds, Tesuque, watercolor, 3.75” by 5.5” (circa 1938). Collection of E. J. Guarino

After acquiring Dancer by Patrick Swazo-Hinds, I learned that although the artist had been adopted by a family in California, each summer he returned to Tesuque Pueblo. This shuffling between two cultures most probably influenced the style of his art. Much of the artist’s work combines the traditional and modern, reflecting the time he spent at Tesuque as well as his exposure to non-Native artists. The work of Patrick Swazo-Hinds was different from that of other Native artists during the 1950s since his paintings were often abstract and rarely made overt reference to his Native American heritage However, around 1964, Swazo-Hinds began incorporating Native American imagery and themes in his work. The fact that the piece I acquired was so polished and is clearly a portrait of a Native American indicates that the artist was thinking of his heritage at an early age.

Male Dancer Velino Shije Herrara (Ma Pe Wi), pencil study for a painting of dance scene, Zia Pueblo, 16” x 15.5” (circa 1950s). Ex Richard Howard Collection. Collection of E. J. Guarino

Knowing that I was interested in works on paper a staff member at the Chase Trading Post suggested that I take a look at Male Dancer, a pencil study of a dance scene. The work immediately appealed to me for two reasons: it showed the artist’s process and, although it was a study for a larger work, the figure on the left is so powerfully rendered that it seems to be walking out of the page to the viewer.

As with the work of Patrick Swazo-Hinds, I knew nothing about Velino Shije Herrara (Ma Pe Wi). With a little digging, I discovered that the artist had created a number of murals, perhaps the most famous of which are full-size examples of his work that adorn the walls of the bunkhouse at the Pritzlaff Ranch in San Ignacio, New Mexico. Ma Pe Wi was proud of he fact that he was a self-taught artist. Although he had no formal training he was able to successfully combine realism with abstraction, often in the same work. Usually, figures are portrayed realistically, while the background is rendered in an abstract style. In spite of the fact that he only had a an elementary school education and no formal art training, 1954 Velino Shije Herrara was awarded the prestigious Ordre des Palmes académiques given by France to distinguished academics and figures in the world of culture and education. However, because of his depictions of traditional ceremonies he evoked the ire of Zia elders who ostracized him.

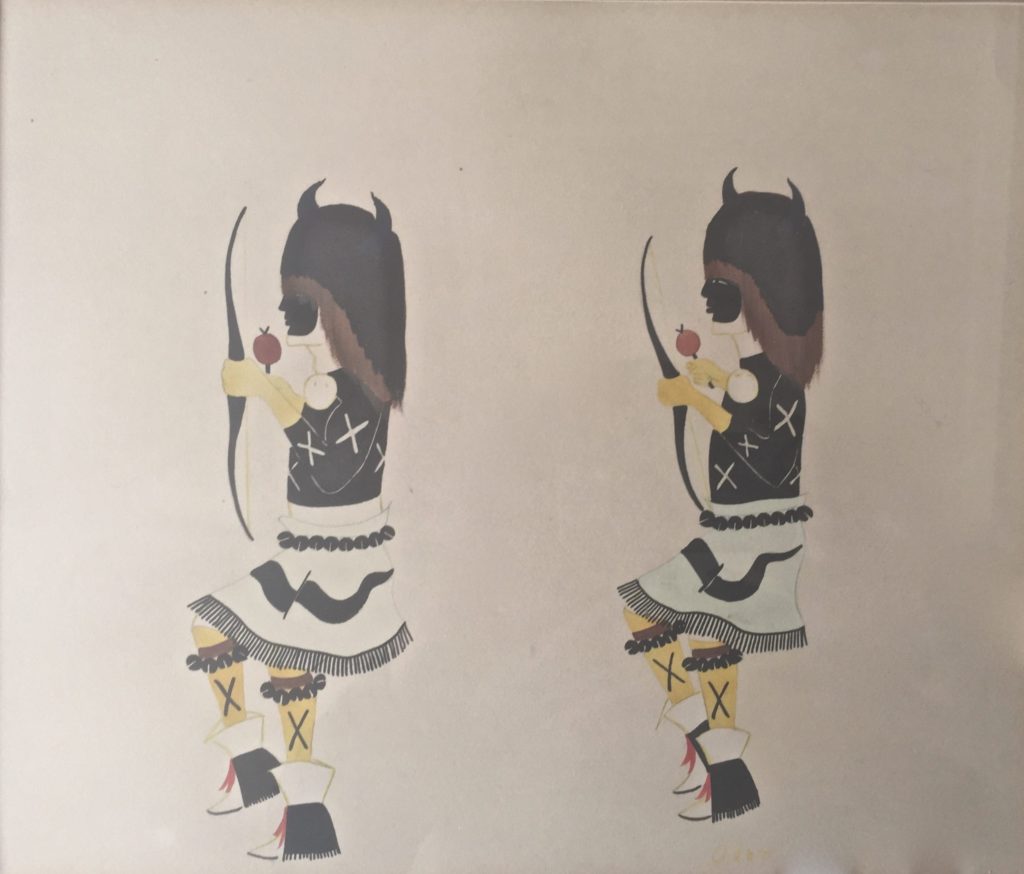

Double Buffalo Dancers by Adam Martinez, gouache, San Ildefonso, 10” x 12” (circa 1950s). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Created using opaque pigments ground in water and thickened with a gluelike material, Double Buffalo Dancers immediately struck me as both colorful and wonderfully evocative of dance movement. I was aware of Adam Martinez when I was offered this gouache painting but only in relation to his ceramic collaborations with his wife Santana. The oldest son of famed ceramic artists Maria and Julian Martinez, he and Santana not only made pottery together but also assisted Maria.

Double Buffalo Dancers reminded me of paintings I had seen by Julian Martinez and I wondered if Adam had created a large body of works on paper. When I hit a dead end in my research, I contacted Bruce Bernstein, Executive Director at the Ralph T Coe Foundation for the Arts, who informed me that “. . . Adam didn’t paint very much . . . . Adam’s village and family responsibilities precluded him from ever being active until the last few decades of his life. All four Martinez boys painted and sold paintings through their parents store, located in the front of their home. Like their father’s paintings they are usually plainer scenes, many of them secular in nature.”

It is unfortunate that Adam Martinez didn’t produce more works on paper. Double Buffalo Dancers is bold and highly detailed, giving the view a sense of this particular Pueblo dance. I will certainly be looking for more examples of paintings by this artist, rare though they may be.

As I considered the three works, I intuitively felt that Dancer by Patrick Swazo-Hinds, Male Dancer by Shije Herrara (Ma Pe Wi), and Double Buffalo Dancers by Adam Martinez somehow belonged together and I could picture them hanging side by side. One of the important aspects of collecting is that works “fit” with the rest of the collection and I sensed that these three works on paper not only helped fill a gap in my collection but complemented each other. Today displayed together in my apartment as seen below:

|

|

|

Native works on paper from the early to mid-20th are a bridge in the collection between the ledger drawings of the 1800s and the modern and contemporary works of the 20th and 21st centuries. This is an area I have just begun to explore and I expect it will be fascinating to see what interested Native artists, working with pencil or paints, during the 1920s, 30s, 40s, and 50s and even the 70s. I am excited to see what I will be able to find. Let the quest begin.