Collector's Corner

GIFTS FROM CLAY MOTHER: Native American Ceramic Art

More than thirty years ago I started a collection though I had no idea that I was doing so. During that period there were a number of gallery exhibits in Manhattan that focused on Pueblo pottery, including a gallery in Greenwich Village called Common Ground that specialized in Native American art. It was there that I first saw huge ceramic ollas, which were completely unknown to me. Perhaps the deciding factor was an exhibit of Acoma pottery at the Brooklyn Museum. For many years I had admired Chinese, Japanese, and Greek ceramic art, but I knew nothing about Pueblo pottery. After some research, I realized that, even on a high school teacher’s salary, Acoma pottery was not beyond my reach. I became obsessed with it, especially the work of Lucy Lewis and her family. It took me a while longer to understand and appreciate the work of artists from other pueblos, particularly that of Maria Martinez. Although over the years my collection has grown to encompass basketry, beadwork, sculpture, paintings, drawings, prints, and, most recently, photography, I consider ceramic art the heart of the collection.

I find it astonishing that many who consider Chinese, Japanese, and Greek ceramics to be art relegate those produced by Native Americans to the realm of craft. Native American artists reach into the earth and from the clay they dig create exquisite ceramic art without employing a potter’s wheel and, with few exceptions, sans the use of a kiln. Through the sheer power of their minds and hands, Native artists create stunning ceramic works that consistently transcend craft.

Jar with shawl designs by Dextra Quotskuyva, Hopi-Tewa, 6”w X 3”h (2000). Photo courtesy of King Galleries.

Hopi pottery is noted for its finely drawn polychrome designs and a unique, yellow-orange coloration know as the “Hopi blush,” which is produced by firing iron rich clay outdoors, using aged sheep dung. Dextra Quostkuyva Nampeyo is one of the masters of this form. However, she sometimes creates works that are minimalist in nature. Her jar with shawl designs is an example of artistic restraint. The piece has a wide shoulder with a small neck and is polished in a vertical manner, which creates an “onion skin” quality. The only painting on the piece consists of textile designs in the form of two bands. The black band has polished white areas with arrow designs. The red section is fully polished. The shapes of the sections are smaller at the base, wide at the shoulder, and then are smaller again at the neck. However, it is the the striking blushes on the surface of the piece that are visually arresting. The work is a subtle, yet daring, experiment on the part of the artist.

Large wide plain ware shoulder jar by Mark Tahbo, Hopi-Tewa, 10”w x 5” h (2001). Photo courtesy of King Galleries.

Garrett Maho is widely known for exceptional painting on his ceramic works, but some of his most interesting pots are plain ware pieces that achieve their beauty through simplicity of form, a “blush” that ranges from white to orange, and polishing techniques that produce a textural quality. The artist’s large, wide plain ware shoulder jar is an example of this aspect of Maho’s art. The jar’s intrinsic beauty is achieved by the absence of any decoration that could distract the eye and it is a bold decision to attempt such a pot. Should the piece have any imperfection there is nothing that can be done to hide that fact. The piece is solely about form and hue – the flawless shape and the delicate

variations of yellow and orange of the Hopi blush. The jar is Native minimalism at its most subtly subversive.

Large Jar with Dragonflies and Cloud Spirals by Debbie Clashin, Hopi-Tewa, 11.75”w x 5”h (2018). Photo courtesy of King Galleries.

Inspired by classic Sikyatki-style pottery, which has a wide shoulder and a slight neck, Debbie Clashin’s large jar is painted with dragonfly and cloud spiral designs. The dragonfly designs are symbolic since the insects are considered messengers who carry prayers to the Creator. The piece was traditionally fired, which created delicate blushes on the surface of the jar. It is astonishing that such an exquisite work of art began as a simple lump of clay. Much as a sculpture does, the artist, using skill, technique, and inspiration, transformed simple materials into a unique creation.

Jar with Ten Interlocking Parrots by Rainy Naha, Hopi-Tewa, 7.5”w x 5”h (2018). Photo courtesy of King Galleries

The design known as the “interlocking” or “tumbling” parrots was originated by Rainy Naha, Her Jar with Ten Interlocking Parrots employs this decoration, which is a prime example of abstraction, something that has been employed by Native American artists since pre-historic times and long before the term abstract art was coined. The shape of the piece allows both the top and bottom parrots to be easily seen. In addition to a high polish and a white clay slip, the jar has a parrot motif: there are five sections of interlocking birds for a total of ten. Each bird is painted with various Hopi-Tewa designs with additional clay slips applied for the colors. Containing a variety of designs, each of the parrots is one of a kind.

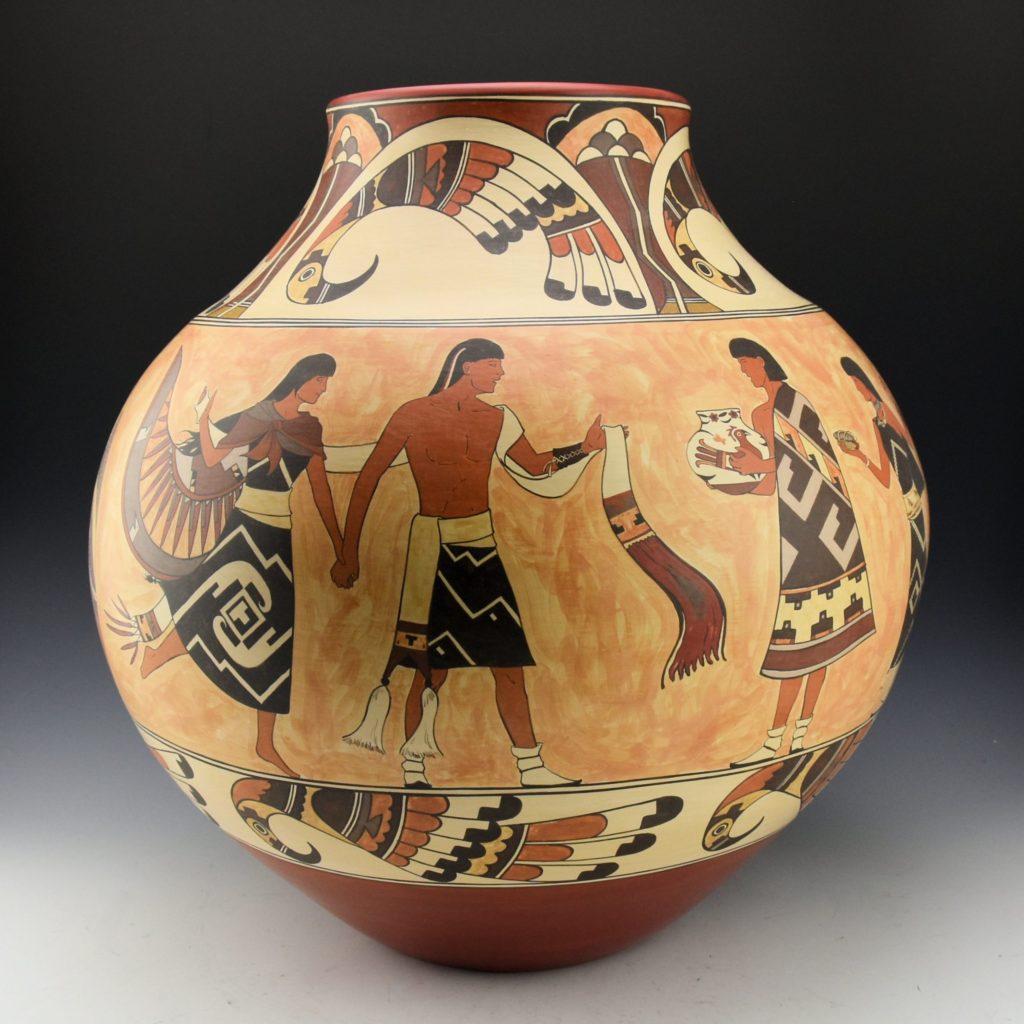

Parrot Girl Storage Jar by Juan de La Cruz and Lois Gutierrez, Santa Clara, 14.25”w X 15.25”h (2018). Photo courtesy of King Galleries

Some contemporary Native American ceramic works are based on utilitarian shapes, others on those that were introduced such as the wedding vase. Created by Juan de La Cruz and his mother Lois Gutierrez, their large parrot girl pot is a modern interpretation of a storage jar, a form that was in use until the introduction of metal containers. Lois Gutierrez formed the massive piece and her son painted it with intricate polychrome designs and figures.

The jar is decorated with scenes from a Pueblo story – the marriage of Tayi P’i who met her future husband while she was still in the form of a parrot. One section of the piece shows her father presenting gifts to his daughter’s in-laws to be. Tayi P’i tested her new husband’s trust in her by making him promise not to open his eyes until they had arrived safely at their home. When they had done so, Tayi P’i shook forth gifts her father had hidden in her wings and then transformed into a beautiful woman. It was then, and only then, that she told her husband that he could open his eyes.

Large Wide Jar with Dancers and Jaguar by Al Qöyawayma, Hopi, 14”w X 10”h (2017). Photo courtesy of King Galleries

Large Wide Jar with Dancers and Jaguar (Detail)

Based on a prehistoric form, Al Qöyawayma’s Jar with Dancers and Jaguar is wide with a low, sharply defined shoulder. The figures were pushed out from the inside of the piece and look very much like those found on Wedgewood jasper ware that was developed in England in the 1770s. A procession of dancers, most holding musical instruments, encircles the piece. While the jar is highly polished, each of the figures has a matte finish. Adding humor to the piece, the last figure is that of a small boy who is being chased by a jaguar. The result is a stunning work of art.

The idea that all pottery produced by Native American ceramic artists is simply craft is unenlightened. Perhaps it is the humble material with which Native American ceramic artists work to create their art that is the stumbling block for some people. Native artists take clay – essentially dirt – and transform it into works of wonder and beauty. Clay is very important to Native American ceramic artists, particularly those who are Pueblo. Prayers are said when it is taken from its home — the earth — and while it is being prepared for making pottery. The resultant ceramic creations are gifts of Clay Mother, the Earth itself, and are works of art on a par with their Japanese, Chinese, and Greek counterparts.