Collector's Corner

I: Rick Bartow’s Self-Portraits

Over the centuries numerous artists have produced likenesses of themselves in paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, and photographs. A self-portrait affords an artist the opportunity to control how he or she wishes to be remembered through a work that might be serious, introspective, comic, or even self-deprecating. Some artists create numerous self-portraits over the course of a lifetime; others may create a few or only one; and there are those who do not produce any.

Portrait of a Man by Jan van Eyck, Early Netherlandish, oil on wood, 10” x 7.5” (1433), The National Gallery, London.

As a genre, the earliest self-portraits can be traced to antiquity. In 1365 B.C. Bak, the Pharaoh Akhenaten’s chief sculpture, produced a self-portrait. During the Pharaonic Period painted self-portraits were also produced. In ancient Greece, the sculptor Phidias included an image of himself in his sculpture of the Battle of the Amazons on the Parthenon. There are also written references to painted self-portraits in ancient Greece, but none have survived. In later periods in Europe, the earliest self-portraits are found in illuminated manuscripts, frescoes, and paintings of the thirteen and fourteen hundreds. The earliest self-portrait on panel in Europe is Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of a Man (aka Portrait of a Man in a Turban and Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban), which was painted in 1433. Self-portraits have a longer continuous history in Asian art than in Europe. Some of these works are quite small and depict the artist in a landscape; some are connected to the illustration of a poem; some are self-caricatures; and others are formal in nature.

Rick Bartow was among those artists who produced numerous self-portraits, including those that were purely symbolic and at least one in which he portrayed himself as a monkey. These works show the artist at various points in his life – post-Viet Nam, his sobriety following years of alcoholism, the death of his wife, and his approaching death.

I first became aware of Rick Bartow’s art in 2003 and of the first two works I acquired one was a self-portrait. Since then, I have acquired fifteen self-portraits by Rick Bartow, not counting those that are purely symbolic.

Strong Spirit by Rich Bartow, Wiyot, monotype, drypoint/etching, 18“w x 13¼“h (2000). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Strong Spirit was one of the first two Bartow works on paper I acquired and is also the first of the artist’s self-portraits to enter my collection. This print exemplifies the artist’s practice of using various animals to represent different aspects of his personality. Bartow has also employed this device with the raven, the hawk, the crow, the coyote, the bear, the salmon, and many other creatures.

Strong Spirit is a self-portrait with an eagle superimposed over it. In it Bartow is wearing a stars and stripes bandana, something he often did and is reflected in a number of his self-portraits. This bandana is clearly a reference to the time he spent serving in the Viet Nam War. A portion of the left side of the figure’s face is scribbled out so that human and bird look out at the world through the same eye. This blending of imagery gives the piece a transformational quality, an important aspect of the Bartow’s work. Although transformation plays an important role in many Native cultures, Bartow expands the conceit from the traditional concept of humans and animals being able to change into one another to the idea that everything we know is in a constant state of change. The superimposition of imagery and the crossing out of part of the figure’s face gives the print a strong expressionistic as well as surreal quality.

Strong Spirit is one of the first prints the artist made with master printmaker Seiichi Hiroshima and was done about a month after Bartow’s wife died of breast cancer.

Self by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, 1999, drypoint etching on handmade Japanese paper, A/P (#0/20), 13” x 12” (1999). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Rick Bartow produced a large number of self-portraits. Generally, these works are more expressionistic than realistic and contain any number of puzzling elements such as words in a number of languages and what appear to be stray marks.

Self is one of the more naturalistic of the artist’s self-portraits. Here the artist’s nose is prominent, a feature that Bartow often exaggerated. As in most of his self-portraits, Bartow is wearing his iconic eyeglasses. Though his eyes are slightly obscured, he boldly looks out at the viewer with a determined look on his face. Although Rick Bartow frequently depicted himself wearing a Stars and Stripes bandana, in Self he appears to be wearing some sort of hat though little more than the brim is showing. Above this is what might be a medallion. To the right are curious marks that look like some sort of glyphic language (see below). Wondering what these marks might mean, I contacted Wilder Schmaltz, Assistant Director of the Froelick Gallery. “As for that section of the Self drypoint, I believe it is Rick’s stylized version of Kanji – perhaps it says Self or his name? I’ll see if it looks familiar to Charles.”

Self by Rick Bartow (detail).

Sure enough, Charles Froelick emailed me with more information about the strange marks Bartow had inscribed on Self. “That is Rick’s stylized version of his name in Japanese,” he wrote. “That could be the simplest, most direct way to address that… Rick used that ‘signature’ quite a lot after 1994 (his first visit to Japan) . . . sometimes he wrote it over and over on the surface of a work of art. Joe Feddersen [a fellow artist and friend] said he’d joke with Rick and say – ‘Could you make your name any bigger?’ Charles Froelick went on to explain the writing in more detail: “The exact form of Japanese script: my best guess is Katakana. It’s either that or Hiragana but it’s not Kanji . . . my strong hunch and recollection is Katakana! There are 3 Japanese Scripts: Kanji is the oldest and directly from China. Hiragana and Katakana are the others. “

Uhn by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, (#9/10) 12” x 9” (2000). August 19, 2020. Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Uhn is unusual in that it is a side view of the subject. Once again the iconic eyeglasses are included as is the large nose. An uncommon addition is a protruding tooth-filled mouth. In this self-representation, the artist chose to portray himself with long hair. This is unusual since he more frequently depicted himself with short, spiky hair. Rather than looking out at the viewer as in Self, here Bartow seems focused on something beyond the frame, which only he can see.

I wondered about the print’s title and, again, reached out to Wilder Schmaltz. “I don’t have any notes about Uhn so far,” he responded. “Rick’s references, as you know, were myriad – it could be Yurok, Japanese, German, a reference to another artist, or even an exhalation. It’s certainly a self-portrait, whatever the title refers to.”

Dignity/Grace I by Rick Bartow, drypoint etching on Kozo Paper, 19/20, Wiyot, 24”h x 17”w (2010). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

At first glance, Dignity/Grace I seems simply to be a self-portrait. However, the artist chose to cast his image in the form of a death mask, eyes closed minus his iconic eyeglasses. As he did with the words of the title, Bartow also “split” his image and then crossed out the words Dignity/Grace, which are at the bottom right of the page. The print may suggest how the artist wishes to be remembered as well as his concern over his own poor health. The divided image may also signify personal struggles faced by Bartow. Ever the iconoclast, Bartow thumbs his nose at convention: though he seems dead, the artist portrayed himself with a toothpick in his mouth, adding a bit of humor to a somewhat somber subject.

Kokopelli at Sunset by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, monotype, 39” x 21.5” (2003). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Kokopelli at Sunset presented a bit of a mystery. Usually depicted as a humpbacked flute player, Kokopelli is an important cultural figure for a number Native American tribes of the Southwest and petroglyphs of this figure appear throughout the area. In some images, he is represented with strange protrusions that resemble an antenna emerging from his head. Images of this figure are found as far east as Cahokia, located in present day Illinois. Kokopelli is associated with fertility, agriculture, music, and storytelling. Seen in many guises – trickster, healer, seducer, teacher, musician, and bringer of rain – he has become a bit of a pop culture icon in the Southwest where his image adorns scores of businesses and a vast array of tourist merchandise. Considering all this, I wondered why Rick Bartow would choose Kokopelli as a subject, especially since he may have used him to create a self-portrait.

Bartow was a musician and saw himself as a storyteller as well. As an artist, many of the things he did also qualify him as a trickster. This is certainly true of Kokopelli at Sunset, especially if the work is, in fact, another of his self-portraits. The fact that the artist used the word sunset in the title is extremely telling. That time of day is often a metaphor for the later years of life and Rick Bartow was well aware of his mortality because of a number of medical issues.

Whether or not Kokopelli at Sunset is a self-portrait is debatable, but it most likely is one of Bartow’s quirky self-depictions. Here he represents himself completely naked, his hair wild, with two strands resembling an antenna. He is a hunchback, with a daub of red at his mouth and a sagging chest, who must lean on a cane for support. In his left had he holds what, according to Wilder Schmaltz, is a flute, which has finger holes clearly visible along its length. Also, Kokopelli’s nose is very much like the ones seen in other Bartow self-portraits.

Just to be sure, I once again turned to Wilder Schmaltz, my go to resource for all things Rick Bartow. “Thanks for writing with this intriguing question,” Wilder wrote back. “I wouldn’t have necessarily identified this as a self-portrait, maybe due to the unusual expression – though a substantial nose often did denote that Rick was depicting himself. Looking at a companion piece, Kokopelli Dance (2003) the features and expression seem to be very much a self-portrait in keeping with many of the others that he executed over his career . . . I believe that if the one Kokopelli is a self portrait, as it seems to be, that the other is very likely one as well.” As far as I was concerned, the matter was settled.

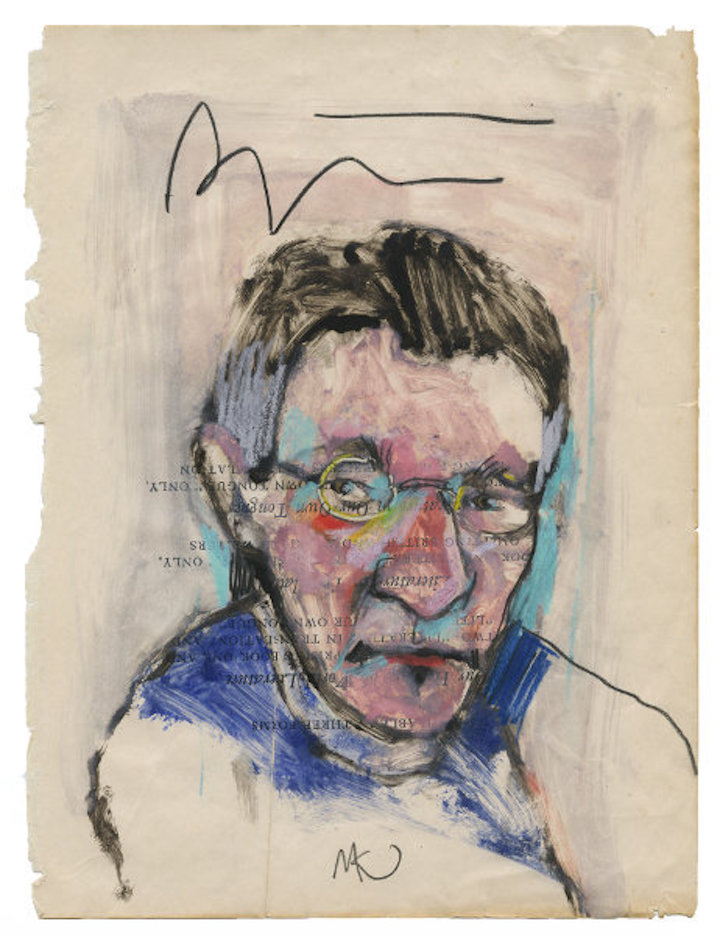

Untitled (Self-Portrait with Glasses) by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, monotype, 10” x 7.5“ (circa 2000). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Untitled (Self-Portrait with Glasses) is the newest work on paper by Rick Bartow to enter my collection. This work interested me for a number of reasons: it was a strong self-portrait by the artist; the image was created over a piece of paper with printing already on it; and, on close inspection, the work has the quality of a painting. When I acquired this monotype Wilder Schmaltz commented that the work is “particularly special – the text showing slightly behind his face, that sidelong look, and leaning angle of his body, he seems to be listening closely, lending an ear.”

However, I was particularly curious about one aspect of the work: the writing on the paper that Rick Bartow had employed since the printing looks backwards and upside down. Again, I turned to Wilder Schmaltz to inquire if he had any thoughts on the topic.

Untitled (Self-Portrait with Glasses) by Rick Bartow (inverted, detail).

In response to my email, Wilder sent detailed photos of Untitled (Self-Portrait with Glasses) in which the image had been inverted and turned upside down. He also wrote back saying, “It looks like a sort of advertising page for different volumes of world literature, ‘AVAILABLE IN THREE FORMS’. My feeling is that this page and text appealed to Rick aesthetically, he liked the text as text, rather than there being any great relevance in the written content itself.”

Looking closely at the writing under the image I tried to make out words. I was able to discern Our Town, a play I had taught many times during my years as a high school English teacher, as well as the word Little, which led me to believe that the other work being advertised was Little Women. I thought these two particular literary works were an odd combination. Perhaps the publisher’s thinking was that each expressed an aspect of American life at two different time periods. I was used to more obvious pairings: Romeo and Juliet with West Side Story. A least another Bartow mystery had been solved and, as usual, it was “sort of”.

Over the course of his career, Rick Bartow produced a significant number of self-portraits, which capture the artist at various points in his life. Often, these works are more expressionistic than realistic and contain any number of puzzling elements – lines, dots, circles splotches, crosses, strange symbols, words in a variety of languages, and those that are crossed out. Bartow frequently exaggerated his features, particularly his nose, but each self-portrait captures the emotionality of a particular time in the artist’s life and reflects the concerns of the artist trying to sort out the complexities and disappointments of life. Like the rest of Bartow’s work, his self-portraits are mysterious, complex, and defy categorization.

Rick Bartow told Charles Froelick, his gallerist, and friend, that he was not a conceptual artist, but that he “tells stories through marks and images.” That statement is as equally true of his self-portraits as his other work. Bartow’s self-portraits are a visual biography of his life, both physically (we can see him age in them) and, more importantly, emotionally.

All images of Rick Bartow’s work are courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Charles Froelick, owner of the Froelick Gallery, and to Wilder Schmaltz, Assistant Director of the Froelick Gallery, for their invaluable help with this article.