Collector's Corner

KACHINA/KATSINA: What’s in a Name?

When I first began to collect Native art in the early 1980s I did so in an encyclopedic fashion. If I saw three pieces of pottery or four baskets, for example, and couldn’t decide which was the best among them I would simply buy them all since prices were affordable. Fortunately, the works were all of good quality. This was a pattern I was to follow for years until I came to understand that I was not a museum; I was a collector. This realization, which should have been obvious, led me to narrow my focus. However, there are many wonderful pieces from those early days, among them kachinas and a few of which turned out to be other types of carvings, that I knew little about. In an effort to learn more about what I had acquired as kachinas, I contacted Joseph Day at the Tsakurskovi Gallery on Second Mesa.

In 1992 I purchased two “traditional” kachina carvings by Manuel Denet Chavarria from Ms. Day’s gallery. Twenty-one years later I still remembered how personable and knowledgeable he and his wife, Janice, were so I decided to contact them to find out more about the kachinas in my collection.

One of the first things I wanted to know was the proper designation for the wooden carvings because, in my research, such figures were referred to as kachinas, katsinas, katsinnam and katsintihu. As a non-Hopi, it was very confusing. “A katsina,” Mr. Day explained, “is an actual spirit being or spirit aspect . . . of everything in the Hopi universe. . . . They manifest themselves in physical form and appear in the katsina ceremonies, popularly but incorrectly known as katsina dances, from February . . . until June.”

Although kachina has long been used in English to refer to the carvings, katsina doll is becoming more common. Also, while katsinas is how the word is pluralized in English, in the Hopi language it would be katsinam.

Although katsinas are spirits that is how people most often, and incorrectly, refer to the “dolls.” Mr. Day added, “Katsintihu is a katsina ‘doll.‘ Tihu means son, daughter, child and, in the case of katsintihu, it should perhaps be translated as offspring.” During a phone conversation, Mr. Day and I agreed that, perhaps, figure or carving would be a better word since doll makes these unique artistic expressions of Hopi faith appear trivial. However, Mr. Day added, “The Hopis who work in my wife’s gallery and in other shops, almost always correct customers when they are looking for kachinas with something to the effect that, ‘We don’t sell katsinas but we do have katsina dolls.’” To a non-Hopi, a religion with 300 – 400 spirit beings may seem complicated. The same could be said, however, about Catholicism with its myriad saints and angels but no one (not even a non-Catholic) would refer to the figure of a saint as a “doll.”

In the course of our phone conversation, I asked Mr. Day if I could Email him photos of the katsina carvings in my collection in the hope that he could identify them and give me some information about each one. To my surprise, it turned out that two of the figures in the collection weren’t katsina dolls.

Yeibichei figure, artist unknown, Navajo, 8.5” tall (date unknown). Donated from the Edward. J. Guarino Collection to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College in memory of Edgar J. Guarino in 2011.

For one carving, I had been given the following information when I acquired it: “Unidentified Navajo or Zuni (?) kachina, artist unknown.” The only thing that was correct about the dealer’s statement was that the piece was Navajo. However, it is not a katsina doll but rather a yeibichei figure, correctly called a yei, according to Mr. Day, who added, “The yeibichei (the Holy People, their Grandfather) ceremony is a major Navajo winter ceremony where the yeis appear and dance.” I should have recognized the carving for what it was because I have a “set” of yeibichei figures in the collection.

Carving of a female wearing a traditional butterfly dance outfit, artist unknown, Hopi, 7.5” tall (date unknown). Donated from the Edward. J. Guarino Collection to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College in honor of Amanda Caitlin Burns in 2011.

Mr. Day identified the second non-katsina figure as “a carving of a female wearing a traditional butterfly dance outfit.” Mr. Day explained, “The butterfly dances are held in August after the katsinam have gone home and are often referred to as ‘social dances’. Although there is definitely a social component to a butterfly dance it is, nevertheless, a ceremony Often, in writing, the term ‘social dance‘ is used to distinguish the butterfly, buffalo and deer dances from the katsina dances but when so used it is not really correct. . . . All of the non-katsina dances at Hopi have a religious component and ritual. In other words, it is not a sock hop.” In the sixteen years that the carving had been in my collection I had believed that it was a katsina doll simply because that is how it had been sold to me. I am grateful to Mr. Day for identifying the piece for what it is.

Kiisa (Prairie Falcon) katsina, artist unknown, Hopi, 9” tall (date unknown). Donated from the Edward. J. Guarino Collection to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College in memory of Katie Guarino in 2011.

I was quite sure that another piece in the collection was a katsina doll but I had no information about it. According to Mr. Day, it is “kiisa, prairie falcon, a racer katsina who comes with a group of other racer katsinam who race with the boys and men of the village.” As with everything in my collection, I acquired the carving of the prairie falcon katsina because of what I felt was its intrinsic artistic value. The figure is beautifully carved and decorated and can be enjoyed simply as a work of art. However, especially as a collector, knowing as much as possible about a piece adds to one’s appreciation.

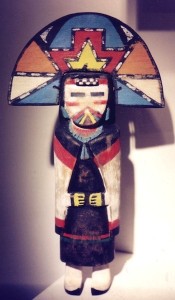

Palhikmana (Dew Drinking Maiden) katsina, artist unknown, Hopi, 13” tall (date unknown). Donated from the Edward. J. Guarino Collection to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College in honor of Kathleen Guarino-Burns in 2011.

In the mid-1990s, I acquired a figure simply identified as a “kachina maiden” because of its elaborate and colorful headdress, the facial decoration and the depiction of its Hopi costume. As soon as I saw it, I bought it. However, since I had not yet begun to take my collecting seriously, I didn’t ask any important questions about the piece. Compounding the problem is the fact that I did not acquire this katsina doll from a gallery but from an antique shop and the owner wasn’t particularly knowledgeable about Native art. According to Mr. Day, the figure represents Palhikmana, Dew Drinking Maiden. However, he expressed some concerns about this piece saying, “I’m wondering about the provenance of this one because the kopatsoki (headdress) is a little off and the red lines on the cheeks should be round.” Clearly, their is a need for further research on this katsina, which it may receive since it is now in the permanent collection of the Loeb Art Center at Vassar College.

On a trip to the Hopi Mesas in 1992, I purchased three contemporary katsina dolls that I consider among the jewels of my collection. In those days, although I was unfocused as a collector I was driven to learn as much as I could about Native American art and culture. However, even at that time my outlook was changing and I no longer saw Native art as “primitive” or viewed it through an ethnographic lens. When I acquired a work of art I did so because I felt it was artistically important. Often, I knew nothing about the “background” of the piece and simply responded to it on an instinctive, emotional level; it either spoke to me or it didn’t. That was the case with the three contemporary kastina carvings I bought. Because I was a neophyte collector, I asked few questions (and definitely not the right ones) and, therefore, received little information.

Honan (Badger) katsina by Manuel Denet Chavarria, Hopi, 11.75” tall (1992). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Upon arrival at the Hopi Mesas, I stopped at the Monongya Gallery where I immediately bought a carving of a Honan or Badger Katsina by Manuel Denet Chavarria. Because I made no inquiries of the gallery staff, I knew nothing more about the piece until I did some research recently. The Honan Katsina is associated with healing and with prayers for the continued growth of medicinal herbs and roots. This katsina is portrayed with black feathers at its head and a long nose or snout. The Badger Katsina is depicted in two forms (my figure is the second of the two) but it is unclear why this is so. However, scholars believer the second version may have arrived at the mesas with a group of later arrivals. According to the Hopi religion, Badger emerged from the earth near Oraibi carrying a great bundle of healing plants and roots on his back, saying that he could cure all types of illnesses. The Badger Katsina is intricately associated with the Honanwungwa, or Badger Clan.

My second stop was the Tsakurshovi Gallery where I purchased two more katsina carvings by Manuel Denet Chavarria but, once again, I asked no questions. However, while on a tour of Walpi on First Mesa I told my guide that I had just acquired three katsina dolls by Manuel Denet Chavarria and I added that I would very much like to meet him. To my surprise, the guide said, “See that door over there? His aunt lives there. Just go knock on her door and she’ll tell you where he lives.” I hesitated but, with her encouragement, I did as she had suggested. When the door opened, I explained what I wanted to know and was graciously invited in. As we sat at the kitchen table, Mr. Chavarria’s aunt gave me his address and directions to his home in a nearby community. When I arrived at his house, Mr. Chavarria was outside working on his car. I introduced myself, told him that I had just bought three of his carvings and said that I greatly admired his work. I was then invited into his studio where I spent over a half an hour happily listening to Mr. Chavarria explain various aspects of his art. It was one of the high points of my trip.

It was only after contacting Joseph Day that I learned the true identities of my two other katsinas as well as a bit about them.

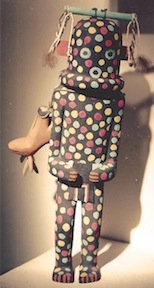

Sulawitsi (Zuni Fire God) Katsina by Manuel Denet Chavarria, Hopi, 12” tall, (1992). Collection of E. J. Guarino

A spot covered katsina figure with a deer slung over its back always delights me when I look at it but, try as I might, I was unable to find out any information about it. Mr. Day said that this katsina is known as Sulawitsi, a word for which there is no English translation, and added, “This katsina is the Zuni fire deity and appears in the Zuni sha’lako ceremony. It’s one of the many Zuni katsinam that have been borrowed by the Hopi and is danced every winter during the kiva night dances. Because of their close geographic proximity, the Zuni and the Hopi have borrowed many katsinam from each other.”

Sikyahote (Yellow Hoote) Katsina by Manuel Denet Chavarria, Hopi, 11” tall (1992). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The other katsina carving I purchased at the Tsakurshovi Gallery is equally spectacular. Called Sikyahote, or Yellow Hoote, it has an array of feathers, yellow and blue paint and star designs. According to Joseph Day, “This katsina appears as one of two side dancers who accompany the Hoote Katsinam. The other is Sakwahote, Blue Hoote. They are spoken of as the uncles of the Hootem.”

When Joseph Day learned that I would be traveling in Arizona during February 2014, he suggested that I re-visit the Hopi Mesas to attend some of the Katsina Ceremonies so that I could put the information he had given me in context. I jumped at the opportunity and was fortunate to witness a katsina dance at Hotevilla.

Yo’whe (Priest Killer) katsina by Randy Brokeshoulder, Hopi, cottonwood, feathers,12“h (2014). Collection of E. J. Guarino

While talking to Mr. Day in the Tsakurshovi Gallery, I noticed a katlsina I had not seen before and, in addition, it was amazingly carved. The figure turned out to be a Yo’whe or Priest Killer katsina made by Randy Brokeshoulder. It is one that is not carved often. This katsina is associated with the village of Awatovi, which has been a ruin since 1700. Awatovi was the first of the Hopi villages to be visited by the Spanish in 1540 but it was not until 1629 that there was a serious effort to convert the inhabitants to Christianity. In that same year, the mission church of San bernardo de Aguatubi was built over Awatovi’s main kiva. During the Pueblo Revolt in 1680 the church was destroyed. However, during the Reconquest plans were made to rebuild the mission but, by 1700, tensions between the Christian converts and adherents of the traditional Hopi religion in all the other villages exploded. Warriors set upon the Awatovi, killing all the men. Many women and children also died and those that survived were dispersed among other Hopi villages. Yo’whe represents the killing of the priest at Awatovi who was supposedly beheaded. A young Hopi told me that the ring in the figure’s ear represents one worn by the priest’s “wife.”

Soyok-wuuti (Ogre Woman) katsina by Randy Brokeshoulder, Hopi, cottonwood, feathers, horsehair, cotton,10“h (2014). Collection of E. J. Guarino

As I was leaving the Tsakurshovi Gallery with the Yo’whe katsina, Randy Brokeshoulder’s car pulled up. He was delivering more of his carvings. One in particular caught my attention – Soyok-wuuti or Ogre Woman. Since I could not get it out of my head, I returned the next day to purchase it.

Spectacularly created by Mr. Brokeshoulder, Ogre Woman represents the disciplinary katsinas who visit homes on First and Second Mesa during the Powamu Ceremony. However, about a week before, these fearsome beings stop at the houses in the villages that have children, giving them each a task – boys are to catch mice with the snare handed and girls are grind well the corn they are given. If Soyok-wuuti and the other katsinas return and there is no food for them the children will be eaten instead. A week later she returns with other monstrous katsinas who bear long crooks and bloody knives. They growl and stomp their feet and refuse the food the children offer them. Next, they recount the misdeeds of each terrified child. Relatives promise that the child has learned his or her lesson and will be good. Other food is given to the katsinas who then move on with much noise. Brokeshoulder has definitely captured the frightening aspects of Ogre Woman.

To appreciate fully the artistic importance of Hopi katsina dolls, it is important to have some understanding of their purpose. According to the Hopi religion, the Holy Katsina Spirits dwell on the San Francisco Peaks and other sacred mountains in the Southwest. From the winter solstice through the middle of July, the katsina ceremonies take place. At this time, masked, costumed men embody the various katsinam during the rituals, allowing the Holy Spirits to be present in physical form. The purpose of the wooden figures, carved from the roots of fallen cottonwood trees, is to teach Hopi children about their religion. According to Joseph Day, “A katsina carving/figure/doll when given by the katsinas to a young girl is, in fact, a prayer that she be healthy, grow up strong, be a mother, and live a long and happy life. The girls do play with them and when they are not, they hang them on the wall. The carvers only started putting the carvings on stands when folks like you and me, with knick-knack shelves, started buying them.”

Over time, collectors and curators became interested in this unique religious art form. Although artists produce katsina carvings for sale, they are, nonetheless, religious icons. Those wishing to collect katsina dolls should first educate themselves. Authentic katsina dolls are made only by Hopi artists and a few Zuni. One of the hallmarks of authentic katsina carvings is, according to Mr. Day, the “accuracy in portraying the katsinas in figure form which is knowledge that non-hopis and non-zunis do not possess.” Poorly made versions produced by Navajo, Mexican, Korean and White carvers are fakes. Simply labeling a figure a katsina doll doesn’t make it a work of art. Because Michelangelo’s sculpture The Ecstasy of St. Theresa is so exquisitely carved it is a work of art while a plastic statue of the same saint is not. The same universal rule applies to katsina dolls.” It should read “Because Bernini’s sculpture.” How I made that mistake I will never know. It is one of my favorite works of art and I’ve seen in on more than one occasion while in Rome.

For more information see Hopi Kachina Tradition: Following the Sun and Moon by Alph Secakuku and Traditional Hopi Kachinas: A New Generation of Carvers by Jonathan S. Day.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Joseph Day who is married to Janice Day, the owner of the Tsakurshovi Gallery, for his invaluable help with this article. Mr. Day has been an observer of the katsinas and katsina ceremonies for over forty years.