Collector's Corner

NORTH FACE: Portraiture in Contemporary Inuit Works on Paper

For many collectors, museum-goers and even curators the term “Inuit works on paper” conjures up images of iconic Arctic wildlife isolated on a page and scenes of life as it was once lived on the land. These two categories, of course, make up a large portion of Inuit artists’ output. However, there is much more. In addition to these, contemporary Inuit artists are producing landscapes, seascapes, cityscapes, nudes, and surreal works. Quite a number of Inuit artists have also created portraits, but little attention has been given to this growing body of work. Sometimes the people represented are identified, but more often than not they are anonymous. Usually, it is the likeness of an Inuk that is portrayed, but sometimes non-Inuit are also immortalized. Portraits are not simply a documentation of what a person looked like at a given moment in time. Instead, artists seek to capture the essence of their subjects.

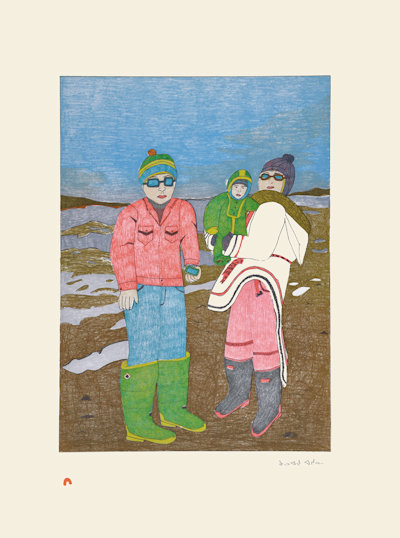

Northern Exposure by Kudluakuk Ashoona, Inuit, Cape Dorset, lithograph on Arches Cover White paper; Printer: Niveaksie Quvianaqtuliaq, 42/50, Cape Dorset. Annual Print Collection # 5, 30” x 22.5”, (2014). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

Although the persons represented in Northern Exposure may be known by the artist as well as in Cape Dorset, they are not identified for the viewer. However, the three anonymous figures look out at us as equals, rather than as ethnographic curiosities. Wearing clothing that is a mix of traditional and contemporary, two adults and a child are portrayed in an Arctic landscape in which most of the ice has melted, indicating that it is most likely late spring or early summer. The work’s title suggests that the artist’s intention is to expose the outside world to contemporary Inuit life since most collectors of Inuit art are located in southern Canada, Europe, and the United States. The three figures appear to be a man and a woman with a child. However, they could just as easily represent two females and a child. The clothing of the three individuals is depicted with great care. The Inuk on the right wears a white amautiq with a fur-lined hood, pink trousers, black rubber boots, and two non-traditional items – sunglasses and what appears to be a knitted cap. This figure holds a small child dressed in a green snowsuit. The other Inuk wears a knitted cap, sunglasses, light red jacket, jeans, and green rubber boots. Although Northern Exposure has a lighthearted quality because of its bright colors, it is an accurate portrait that reveals contemporary life in the Arctic.

Composition (Portrait of a Man) by Itee Pootoogook, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil, 25.5” x 19.5” (2019). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

The use of somber colors creates a serious tone in Composition (Portrait of a Man). Itee Pootoogook reinforces this impression by an inner rectangle drawn to create the illusion of a frame around the image he has drawn. Once again, although the artist and the Cape Dorset community may know the identity of the sitter, the viewer is left to contemplate the face of someone who remains anonymous. We are also left to wonder why the artist chose to create a portrait of this particular person. The smiling man in the turquoise shirt creates a pleasant impression as he looks directly out at us. Beyond his appearance, we know nothing about him.

Fiddler and Drum Dancer by Kananginak Pootoogook, colored pencil, and ink, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 20” x 26” (1991/92). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver, BC.

At its core, Kananginak Pootoogook’s Fiddler and Drum Dancer is a double portrait, which reflects the artist’s interest in the subject of the interaction between non-Inuit and Inuit people. As with many Inuit portraits, the men are anonymous. Both the fiddler and the drum dancer wear clothing representative of their cultures and Kananginak renders their costumes with great attention to detail. The blonde hair and colorful tie and shirt worn by the White man gives the drawing a happy tone. The Inuk wears traditional clothing: an amauti (parka) and on his feet kamik, a soft boot made of caribou skin. Both musicians are clearly intent on their instruments, but also on the task of making music together. Kananginak uses negative space in quite an interesting way – the neck of the fiddle connects the two figures, suggesting that the music they are playing bridges the cultural divide between them.

Composition (Woman) by Shuvinai Ashoona, colored pencil and ink, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 40” x 13” (2006). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

Although the nude has had a long history in the Western art cannon, it is rare in the work of Inuit artists. Throughout history the nude to explore sexuality, power, gender, and religion. Some artists have offered us the human body to contemplate as the most perfect example of beauty – Creation’s masterpiece. Like their peers, contemporary Inuit artists are claiming their right to explore any aspect of the human condition they choose, including the human anatomy. In Composition (Woman), Shuvinai Ashoona offers the viewer the image of a nude woman modestly covering the intimate parts of her body with her hands. The artist has done a number of nudes, some of which identify the person being represented. However, in Composition (Woman) it is unclear whether the image is a portrait of an actual person, a self-portrait or one that is completely imaginary.

For this drawing and a number of others, the artist chose a paper of unusual size: forty inches long by thirteen inches wide, not a typical size for Inuit drawings. Pat Feheley (owner of Feheley Fine Arts, a gallery which specializes in Inuit art) has dubbed them “ribbon drawings” because of the unusual length of the paper on which they were created.

Oonark’s Family by William Noah, Inuit, Baker Lake, pencil and watercolor, 22” x 30” (2005). Photo Courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

During the latter half of the twentieth century, Jessie Oonark was one of the most famous Inuit artists, producing drawings, prints and wall-hangings. As many of her contemporaries did in the late 1950s, Jessie Oonark and her family abandoned a nomadic lifestyle and moved to the settlement of Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake). Married at the age of twelve, over the course of her life Oonark had thirteen children, eight of which reached adulthood and also became artists. One of them was William Noah. In Oonark’s Family the artist has created a self-portrait as well as seven other portraits, which represent his sisters and brother who survived to become artists: Janet Kigusiuq, Victoria Mamnguqsualuk, Nancy Pukingrak, Peggy Qablunaaq Aittauq, Mary Singaqti Yuusipik, Miriam Marealik Qiyuk, and Josiah Nuilaalik. Each has been lovingly rendered.

My Mother and Father (Jessie Oonark and Kabloonak) by Janet Kigusiuq, Inuit, Baker Lake, pencil crayon on paper, 22.5” x 30.5” (2003). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of the Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver, BC.

My Mother and Father (Jessie Oonark and Kabloonak) is a tender portrait by Janet Kigusiuq of her parents that includes the family dog. It was the artist’s mother, Jessie Oonark, who encouraged her to draw as a way of supplementing the family’s small income. Most Inuit drawings arrive at galleries untitled. Any ‘title’ is given either by the co-op or the gallery selling them. However, it is known that the drawing titled My Mother and Father does depict Janet Kigusiuq’s parents. Although the two humans in the scene are depicted wearing traditional clothing, the setting is unconventional. Rather than leaving the background white as she did in her earlier work, the artist uses patches of color, creating an abstract backdrop.

A Portrait of Pitseolak by Annie Pootoogook, Inuit, Cape Dorset, pencil crayon, ink, 26” x 20” (2003/04). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts. Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

In A Portrait of Pitseolak Annie Pootoogook captures her famous diminutive grandmother, Pitseolak Ashoona. Lovingly rendered, the drawing portrays the elderly woman wearing her signature back-rimmed eyeglasses. The only image on the paper is that of Pitseolak standing on a small patch of rocky soil. The background is left blank. This allows the viewer to focus on the details of the individual portrayed: the polka dot headscarf, the lovely face, the black jacket over a flowered skirt, and a cane. This work is at once a remembrance of a beloved family member as well as the likeness of a celebrated artist and a portrait of old age.

Self Portrait by Jutai Toonoo, Inuit, Cape Dorset, acrylic on paper, 30” x 22.5” (2011). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

Originally a sculptor, Jute Toonoo was captivated by the human face. When he saw the drawings of fellow Inuit artist Annie Pootoogook, Toonoo realized that he need not be confined to images of Arctic wildlife and scenes from the past. As an artist, he was free to depict anything he desired. Although he produced works on many themes, sometimes incorporating text, his portraits and self-portraits are among his most powerful creations. Self Portrait shows Mr. Toonoo four years before his untimely death just shy of his fifty-sixth birthday. Set against a blue background with what appears to be an aura around him, the artist, in black shirt, looks out at the world with piercing, inquisitive eyes.

Composition (This is Me in My Coat of Many Colors) by Shuvinai Ashoona, ink, pencil Crayon, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 40” x 13” (2005/06). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

Composition (This is Me in My Coat of Many Colors) by Shuvinai Ashoona, ink, pencil Crayon, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 40” x 13” (2005/06). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

Another of Shuvinai Ashoona’s “ribbon drawings,” Composition (This is Me in My Coat of Many Colors) is a self-portrait. The work is rather straightforward, as self-portraits go. In referring to the piece, the artist stated, “I made this sweater by knitting long pieces of color and then I sewed them together.” Clearly, she was so proud of the sweater that she decided to commemorate it in a drawing that is done in her usual colorful and charming style. As with Composition (Woman), the artist chose a paper that was forty inches long by thirteen inches wide, not a typical size for Inuit drawings.

Tribute by Shuvinai Ashoona, lithograph, 8/50, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 40.5”h x 30”w, Cape Dorset Spring Release #4 (2010) Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

Tribute by Shuvinai Ashoona (detail)

Tribute is a fascinating print on many levels. It is visually interesting because of the sweep of the figure’s arms, the striking face, the use of the color blue and the incorporation of text. The piece is a self-portrait in which the artist has chosen to indicate that she “carries” the history of modern Inuit art by placing on her clothing the names of promoters (such as James Houston and Terry Ryan), artists (including, Kananginak Pootoogook and Napatchie Pootoogook), gallery owner Pat Feheley, collector John Price, and others who have all contributed to making Cape Dorset art what it is today. The print indicates that Shuvinai Ashoona is clearly aware that she is where she is as an artist because of many people and she wished to honor them.

Inuit artists have also created unique symbolic and expressionistic works that have expanded the genre of portraiture. Among these are Pitseolak’s Glasses and 35/36 by Annie Pootoogook, Courting Birds by Saimaiyu Akesuk, and The Student and The Day After by Jamasie Pitseolak.

35/36 by Annie Pootoogook, Inuit, Cape Dorset, collagraph and stencil on Arches white paper; Printer: Sylvia Bendzsa; Edition: 30; 17” x 30” (2006). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts. Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

Perhaps the most modernist (and for some the most surprising) aspect of Annie Pootoogook’s work is her use of contemporary everyday objects as still life. The focus of 35/36, is the artist’s red bra. The work subverts the common Inuit printmaking practice of isolating one iconic image on the page by replacing the expected depiction of Arctic wildlife with a non-traditional article of clothing. The print, at once surprising and humorous, confronts cultural stereotypes head-on since most non-Inuit are stuck in a construct of life in the Arctic as it was lived in the past.

Pitseolak’s Glasses by Annie Pootoogook, Inuit, Cape Dorset, collagraph on BFK Rives white paper; Printer: Sylvia Bendzsa; Edition: 30; 13” x 20” (2006). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts. Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

In Pitseolak’s Glasses Annie Pootoogook once again recalls her grandmother by presenting the viewer with a large, highly detailed image of Pitseolak Ashoona’s iconic eyeglasses that is reminiscent of Pop culture and advertising, both of which have influenced the artist’s work. Annie Pootoogook has created a contemporary still life that is also a moving symbolic portrait of a beloved family member who has died. All that remains behind is an object and the memories it evokes. The work is a masterpiece, so modern in its simplicity.

Courting Birds by Saimaiyu Akesuk, Inuit, Cape Dorset, stonecut and stencil; Paper: Handmade Washi Kizuki Kozo White; Printer: Qiatsuq Niviaqsi, 36/50, 24.5” x 31,” Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection #22 (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts.

Courting Ravens is an abstracted representation of two brightly colored birds. It is large, bold, and decidedly humorous. The piece is so finely printed that it is easy to mistake it for a drawing because of the strokes of color moving in different directions that are clearly visible. It might seem bizarre to consider this work a portrait but, based on what the artist has said about this print, it certainly falls into the genre. Although the title leads the viewer to believe that the work is about romance, the artist has stated in interviews that the two figures actually represent her and a good friend and is about the look they often give each other that often turns into a laugh. The two birds are, therefore, stand-ins for Saimaiyu Akesuk and her friend. Generally, it is the Cape Dorset co-op that titles prints. If the artist had titled the print she would probably have assigned it one that suggests two friends rather than two lovers.

The Student by Jamasie Pitseolak, Inuit, Cape Dorset, hand painted dry-point etching 2/15; paper size: 31.5” x 44;” image size: 23.5“x 35“(2010). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of the Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver, BC.

The Student and The Day After are a pair of narrative prints that are also a psychological portrait. It is necessary to view both works in order to understand exactly what the artists has portrayed.

The Student, the first of Jamasie Pitseolak’s print pair, shows a boy (the artist) in a bathtub just prior to being abused by one of his teachers. The color pink is used on this figure to symbolize childhood innocence, while slash marks across the scene are painted chartreuse, indicating the artist’s revulsion about the act that is about to take place. The abuser stands beside the tub, his eyes, chest, genitals, and feet colored the same sickly yellow-green as the slash marks. The artist has also drawn him with what appears to be two penises. In addition, Pitseolak used strong marks over the image of the attacker as if to cross him out.

The Day After by Jamasie Pitseolak, Inuit, Cape Dorset, hand-painted dry-point etching, 2/15; paper size: 19.5” x 15;” image size: 11.75“ x 8.5 “ (2010). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of the Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver, BC.

The Day After, the second print of the pair, shows the aftermath of the previous day’s attack. This time the teacher is painted completely green with an asterisk, a star, and other markings coming out of his mouth, representing expletives and threats, as they do in comic book art. The student, almost formless and looking much like a limp pink rag, is held by his neck near his desk. As in the first print, the teacher is negated by slash marks. The difference in size between the two prints also carries emotional weight. The Student measures twenty-three and a half inches while The Day After is much smaller at only eleven and three-quarter inches by eight and a half inches.

It took a great deal of courage for Jamasie Pitseolak to reveal that he had been sexually abused but more in such a public way through his art. Both The Student and The Day After are a far cry from the expected Inuit images of brightly colored Arctic animals and scenes of nomadic people hunting, fishing and building Igloos, but they reflect another aspect of Inuit life by presenting a psychological portrait of an artist who has undergone an unjust and painful experience.

Although they are more known for images of Arctic animals and scenes of a past nomadic life, many contemporary Inuit artists are refusing to be confined solely to these subjects and are creating works in a wide range of genres, portraiture among them. Although portraiture has fallen out of fashion in some quarters, it remains popular with the public. Many Inuit artists create produce portraits of beloved family members, highly regarded community members, and friends, as well as self-portraits although many of those portrayed are not identified. Although portraiture is produced by Inuit artists, it is rarely focused on as a genre. This is unfortunate, but collectors and curators have become aware of their existence and significance. One of the most important aspects of contemporary Inuit portraiture is that we are seeing Inuit people as they see themselves rather than as others see them, which has been the case for so long.