Collector's Corner

SEDNA, MISTRESS OF THE SEA: The Inuit Goddess in Myth and Art

Every culture has its share of mythological stories populated by strange beings, interfering gods and goddesses, and larger-than-life heroes. The Inuit of Arctic Canada have a treasure trove of such tales. Among the many interesting characters in the Inuit cosmos is Sedna, goddess of the sea and marine animals. Sedna, who is also known by a number of other names such as Taleelayo (The One Down on the Sea Bottom) and Nuliajuk (Mother of All Beasts), is one of the most important figures in Inuit culture. Part woman, part fish, she most resembles a mermaid. It is Sedna who controls the bounty of the sea. If angered, she can be extremely vengeful, withholding the fish and sea mammals upon which the Inuit rely. It is she who decides whether humans eat or starve.

There are many variations of Sedna’s story, but in each one, her father takes her out to sea in his kayak, throws her overboard, and, as she clings to the side of his vessel, he chops off her fingers and she sinks to the depths below. Contemporary Inuit artists generally portray the goddess minus the gory detail of her missing fingers, and she is often presented as more playful than vindictive. Traditionally, hunters depended on Sedna’s goodwill to release the creatures of the sea so that they could have success. If a taboo had been broken or the goddess had been disrespected in any way, she first had to be placated. It was believed that she held the fish and sea mammals in her hair and that, when angered, a shaman had to enter into a trance, visit her, and appease her by listening to her complaints about the transgressions committed against her, singing to her, and combing her hair with a bone comb, which she could not perform herself because she had no fingers. Appeased, Sedna would then set free all of the animals she had restrained. In modern depictions, Sedna is often portrayed as vain.

Sedna is also the Mistress of the Underworld, and the Inuit believe that all who die must spend a year with her before going to Quadliparmiut, the Happy Place, where it never freezes and food is always plentiful.

As a collector, Sedna has fascinated me for many years but, until recently, only two artworks portraying the goddess (Sednas and Bird Spirits/Spirit Faces, which was donated to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College in 2009, and Sedna with Fish, a sculpture by Isa Aupalukta) were in my collection. Both were acquired in 2003.

Sednas and Bird Spirits/Spirit Faces, double-sided drawing by Irene Avaalaaqiaq, Crayon on paper, Inuit, Baker Lake, 21” x 29” (1984). Donated to the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, from the Edward J. Guarino Collection in honor of Amanda Caitlin Burns in 2009. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto

Sednas and Bird Spirits, a double-sided drawing with Spirit Faces on the reverse, is an odd work by Irene Avaalaaqiaq. The piece is unusual not only because the artist drew on both sides of the page but because Sedna is presented in multiple. Also, it is somewhat difficult to determine which are the Sednas and the Bird Spirits. Nonetheless, it is a fascinating work.

Sedna with Fish by Isa Aupalukta, Inuit, Inukjuak, soapstone, 6¾” x 6¾” x 1½” (2001). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto

In many ways, Sedna is a strange being, and she is often depicted doing the unexpected. (In one recent work, she is even portrayed taking a selfie of herself with a cellphone.) Sedna with Fish by Isa Aupaulkta is no exception. A bare-breasted Sedna is rather typical. However, seeing her represented as eating a fish is a bit shocking. The sight of the “Mother of All Beasts” eating one of her children is a bit disconcerting. However, even goddesses have to eat.

Over the course of my collecting, I have been very particular about choosing works portraying Sedna. Until recently, none appealed to me. Some images seemed hackneyed, others overly sentimental. In essence, they simply did not “speak” to me. Recently, however, I came upon three works on paper – Composition (Sedna) by Cee Pootoogook, Sedna & Fulmer by Enoosik Ottokie, and Sedna by Simona Scottie – that caught my interest to the point that I immediately acquired them. I also find Out of the Sea by Pitaloosie Saila, Sedna’s Creation, Sedna and Sedna’s Braid all by Ningiukulu Teevee to be fascinating though.

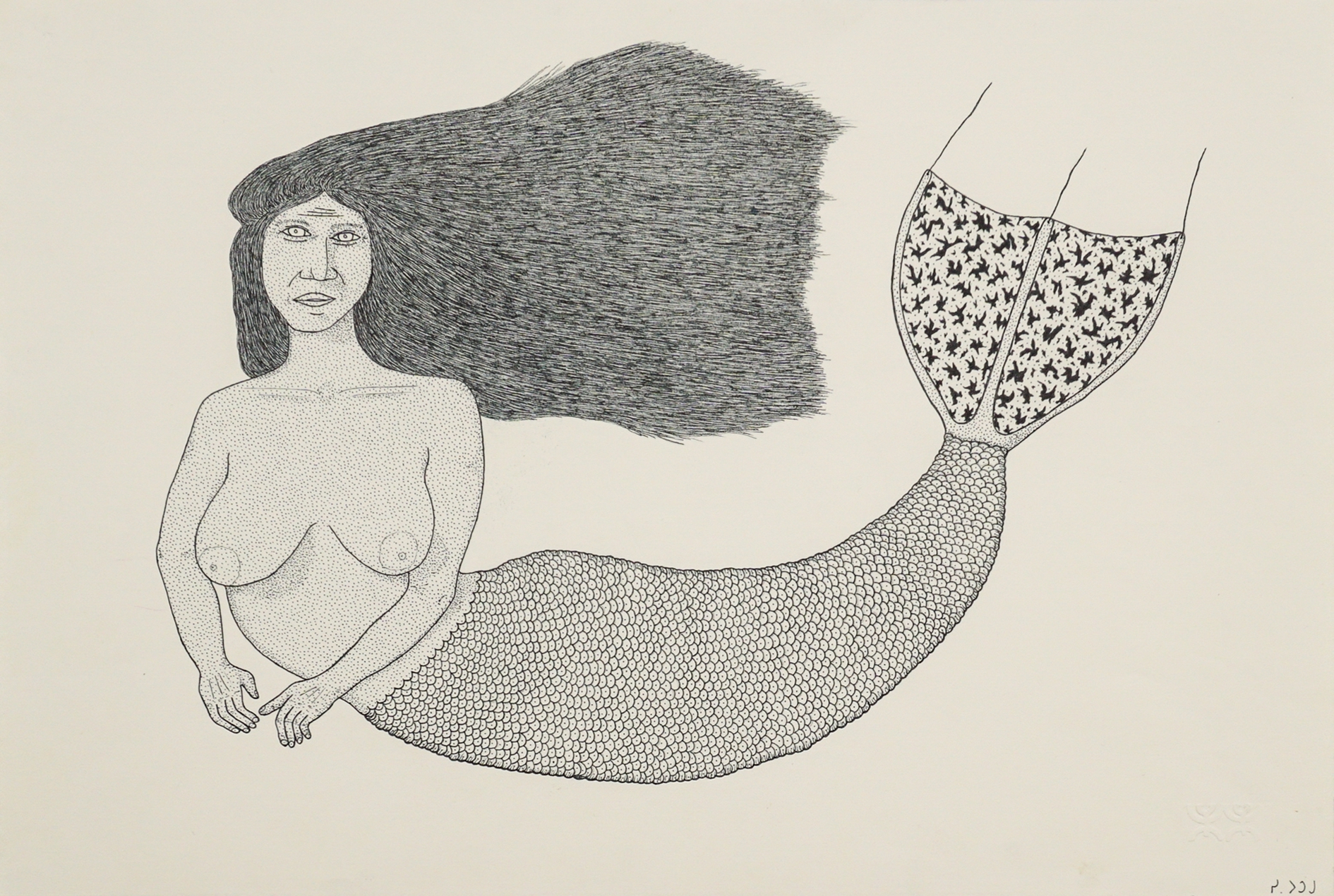

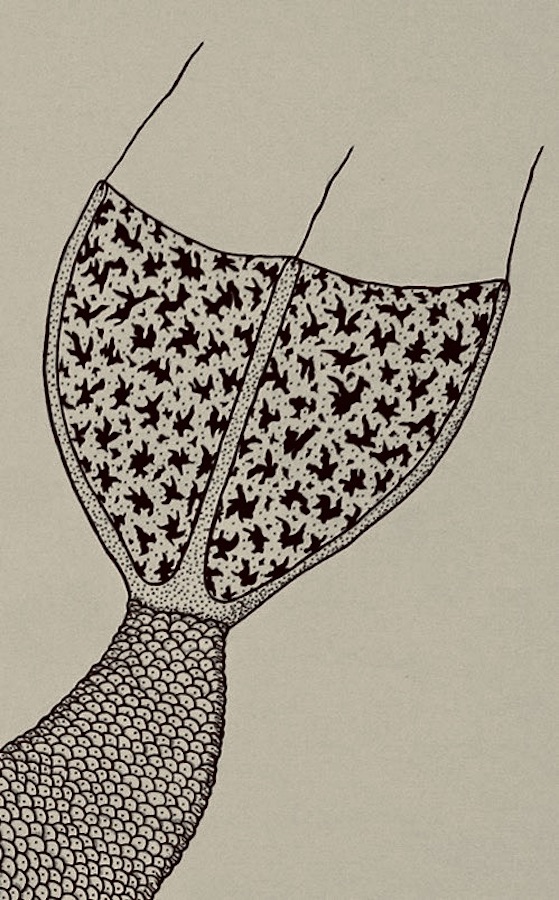

Composition (Sedna) by Cee Pootoogook, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), ink, 13” x 19.25” (2010). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Composition (Sedna) by Cee Pootoogook (Detail).

To anyone familiar with images of Sedna, the portrayal of the goddess in Cee Pootoogook’s Composition (Sedna) appears rather straightforward and normal (for Sedna, that is): long flowing hair, bare breasts, the lower body covered in scales, and a tail. However, when Sedna’s tail is examined more closely, something curious and surprising is revealed: rather than sea creatures, the goddess’ tail is covered with birds. As an artist, Cee Pootoogook often does the unexpected – an image of Arctic lice; a swarm of mosquitoes on a blood-red background; a green polar bear; a yellow polar bear surrounded by fish, each a different color of the rainbow; one brown fish amid an entire school of blackfish; a teapot with a serpent spout and a bird’s claw handle; or a polar bear dressed in clothing. So, a Sedna with an odd tail is rather par for the course for this artist and adds to the drawing’s appeal. As a collector, I’ve come to expect the unexpected from Cee Pootoogook, and I am always curious as to how he will surprise me. The phrase “curiouser and curiouser” certainly applies to much of his work.

Sedna & Fulmar by Enoosik Ottokie, Kinngait (Baker Lake), stonecut & stencil, 16” x 24.25” (2019). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

The first thing that one may wonder with regard to Sedna & Fulmar is exactly what kind of bird is a fulmar? Unless one lives in northern climes, is an ornithologist or avid birder, this species may be totally unfamiliar. The fulmar, also known as the northern fulmar and the Arctic fulmar, resembles a gull, but it is actually related to the petrel and the albatross. These hardy birds exist in large numbers and feed over the open ocean; their sense of smell is so strong that they can detect fish, squid, and crustaceans in the water below them and dive as deep as ten feet to reach them. The birds spend a brief breeding season in colonies in seaside cliffs and then return to the open ocean. When threatened by another bird the fulmar projects a foul-smelling, bright orange sticky vomit, which clings to a predator’s feathers, destroying their waterproof coating and eventually causing them to drown.

The scene illustrated in Sedna & Fulmar is a dramatic one. The goddess, greenish like the color of seaweed, and the fulmar, black, appear to be arguing, but about what? Is the bird trying to prey upon one of Sedna’s sea creatures? At the same time, the fulmar, its mouth open, may be about to project its malodorous vomit at Sedna though attacking a goddess is never a good idea. Sedna’s hands are rather large, especially the right one, and she appears ready to strike the bird with it. Frozen in time, we may never know exactly what is transpiring, but it is intriguing to ponder the possibilities. Adding to the visual interest, both the body of Sedna and the fulmar are delineated with lines, giving the image a tactile quality and making it appear to be a drawing.

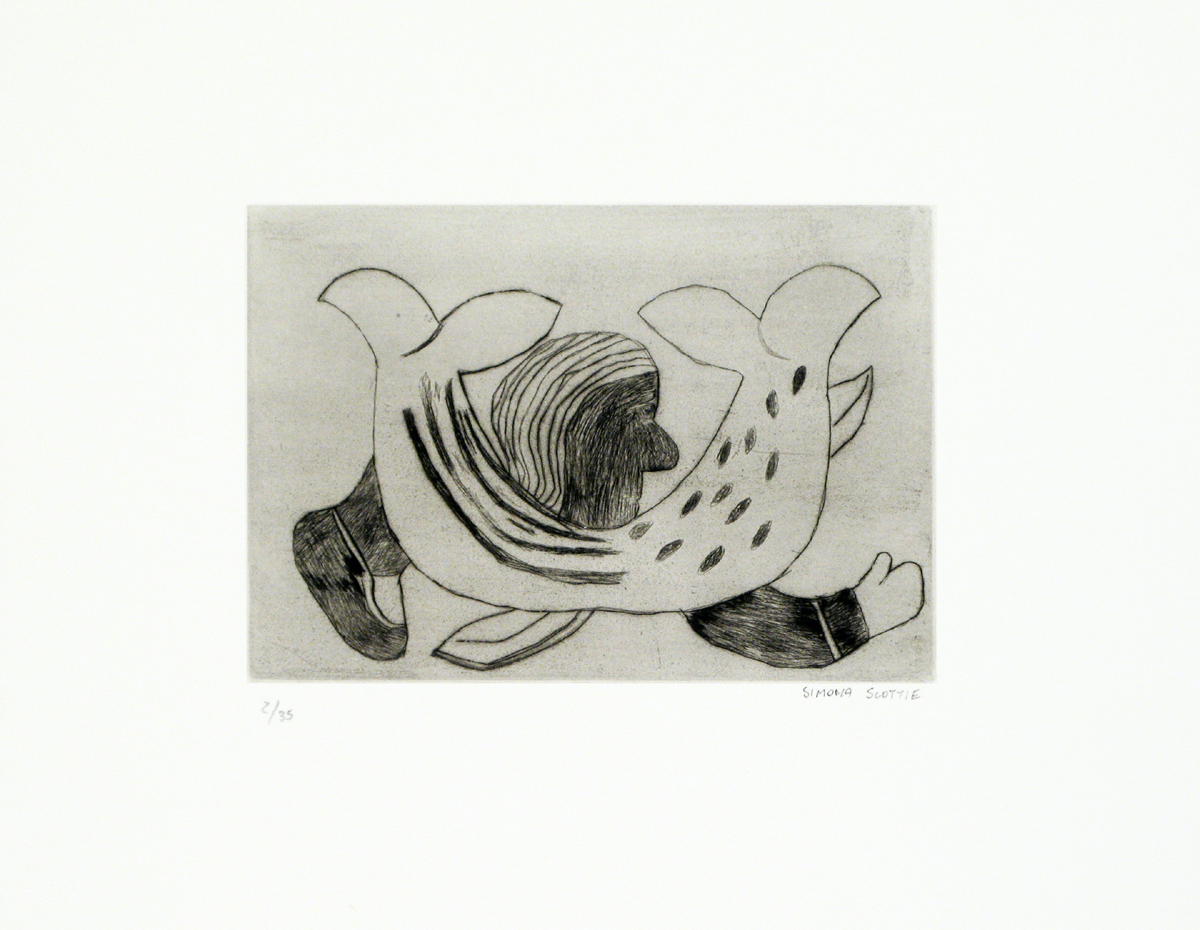

Sedna by Simona Scottie, Baker Lake, etching, ed. 2/35, 12” x 15.5” (2001). Collection of E. J. GuarinoImage courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

What to make of Sedna by Simona Scottie? My first impression was that the image was strange and confusing, but I just couldn’t get it out of my mind and I became fascinated as to why the artist chose to portray Sedna in the way she did. Is Sedna transforming? Is she in the process of devouring a sea creature? The print is only nominally representational. It more correctly falls into the category of what has become known as the Inuit Surreal.

A surrealistic strain has run through Inuit art since its inception and continues to do so. Works of this type contain multiple perspectives, distortions, emotional intensity, seeming spontaneity and, often, strange creatures. Sometimes, as with Simona Scottie’s print Sedna, a work may seem to be just a jumble of images. To some, this aspect may be off-putting while others find it to be fascinating. I am definitely among the latter group.

Although Simona Scottie’s imagery may, at first, perplex the viewer, the artist has created another way of seeing. Her vision allows us to view the world through her imagination. We are being asked to go beyond the boundaries of reality and representation which, for many, is a very uncomfortable place.

Out of the Sea by Pitaloosie Saila, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Stonecut & Stencil, 21.5” x 28” (1986). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

An image of Sedna that is a particular favorite of mine is Pitaloosie Saila’s depiction in Out of the Sea. Pitaloosie has an extremely subtle sense of humor that is often missed by viewers of her work. As she often does, the artist creates an image that is quite minimalist, delineating the goddess and the sea with what appear to be a few effortless strokes. Viewers, however, should not be deceived into believing that Pitaloosie is not in complete control of her art. She always knows exactly what she is doing and Out of the Sea is no exception.

There is a lightness to the scene in Out of the Sea. The water has been dealt with in an abstract fashion, using the color blue and taking up very little of the page. It is Sedna who dominates, and rightly so. Although she is most frequently depicted bare-breasted, Pitaloosie, instead, teases and tantalizes the viewer by placing Sedna in an outfit that reveals just enough décolletage to titillate a bit. As for the goddess’s face, is she wearing a look of surprise or is she pursing her lips, like many a starlet, for her audience?

Like other contemporary Inuit artists, Pitaloosie has chosen not to show Sedna with bloody stumps, indicating her missing fingers. Her artistry is much more nuanced. Instead, the fingers of the goddess’s left hand are elongated and a bit odd looking. In her right hand she holds an ulu, an extremely sharp cutting tool, which is, perhaps, a sly, but non-gory reference to what her father did to her. The ulu may also indicate that Sedna is simply looking for a meal.

As for Sedna’s tail, Pitaloosie depicts it in her own distinctive way – through the use of brown and black and the suggestion of shape. She avoids the expectation of green and the use of scales as unnecessary.

Pitaloosie employs positive and negative space in ways that are decidedly modernist and her use of line and one simple color to create the idea of ocean in the mind of the viewer is remarkable.

Sedna’s Creation by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Stonecut, Paper: Kizuki Koso White; Printer: Qavavau Manumie &Ashoona Ashoona, ed. 50 241/4” x 321/4” (2019). Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts Toronto and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Ningiukulu Teevee is noted for her unique interpretation of Inuit life and, in particular, Inuit myths. Sometimes her approach is humorous, other times not. She has created a number of prints and drawings in which she depicts Sedna in unexpected ways. One of her most curious representations of the goddess can be seen in Sedna’s Creation. In this print, Ningiukulu does not reveal the deity in her entirety. Instead, she shows only the forearm and fingerless hand of one arm. In many versions of the Sedna myth, the bounty of the sea – all of the myriad sea creatures – are held within the goddesses hair, but in Sedna’s Creation they come forth from her hand. Using only the white of the page, black for the sea mammals and fish, tan for the goddesses forearm and fingerless hand, and blue for her tattoo, Ningiukulu Teevee creates an unconventional image of Sedna.

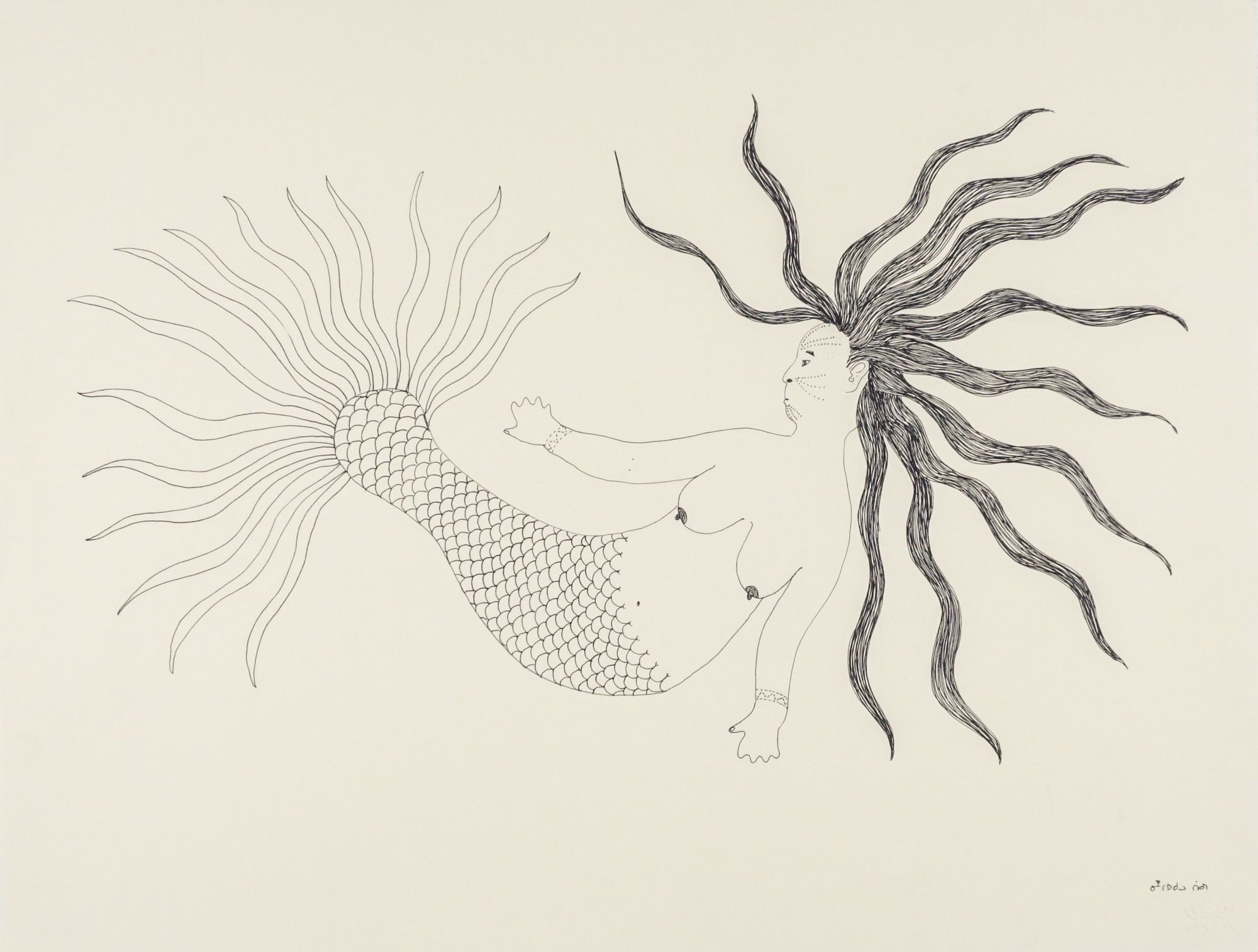

Sedna by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Ink, 20” x 26” 2005. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Once again, Ningiukulu Teevee produced a strikingly original image of the goddess in her drawing titled simply Sedna. As expected, Sedna has fish scales on her lower body, and her amputated fingers are stumps. Although Ningiukulu conceived of a bare-breasted Sedna with prominent nipples, she has added two extremely odd characteristics regarding the upper and lower portions of the goddess’s body – her hair and her tail. In Ningiukulu Teevee’s drawing the goddess’s black hair is wild, as if she has been hit by a bolt of electricity. The image is almost humorous. Sedna’s tail, which is almost always depicted as a singular appendage is, in Ningiukulu’s hands a white version of the hair. It is safe to say that Ningiukulu Teevee seems to have an endless array of ways in which to portray Sedna.

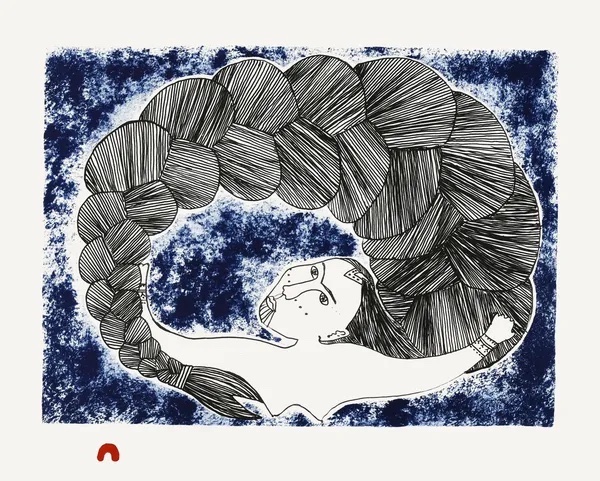

Sedna’s Braid by Ningiukulu Teevee, Cape Dorset (Kinngait), lithograph,Paper: BFK Rives White,Printer: Nujalia Quvianaqtuliaq, 10” x 13”, ed. 50, #14, 2022 Annual Cape Dorset Print Collection. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

Sedna’s Braid is one of the most recent depictions of the goddess. In this portrayal by Ningiukulu Teevee the focus is on the goddess’ hair, which, presented in oversized form, takes up much of the page, which suggests the important role it played in myths about her.

In Sedna’s Braid Ningiukulu Teevee creates an intriguing image with just three colors: the white of the page, black, and blue. Although the braid dominates the page, the print has intriguing details: the facial tattoos of the goddess and, if one looks closely, the missing fingers on the deity’s left hand.

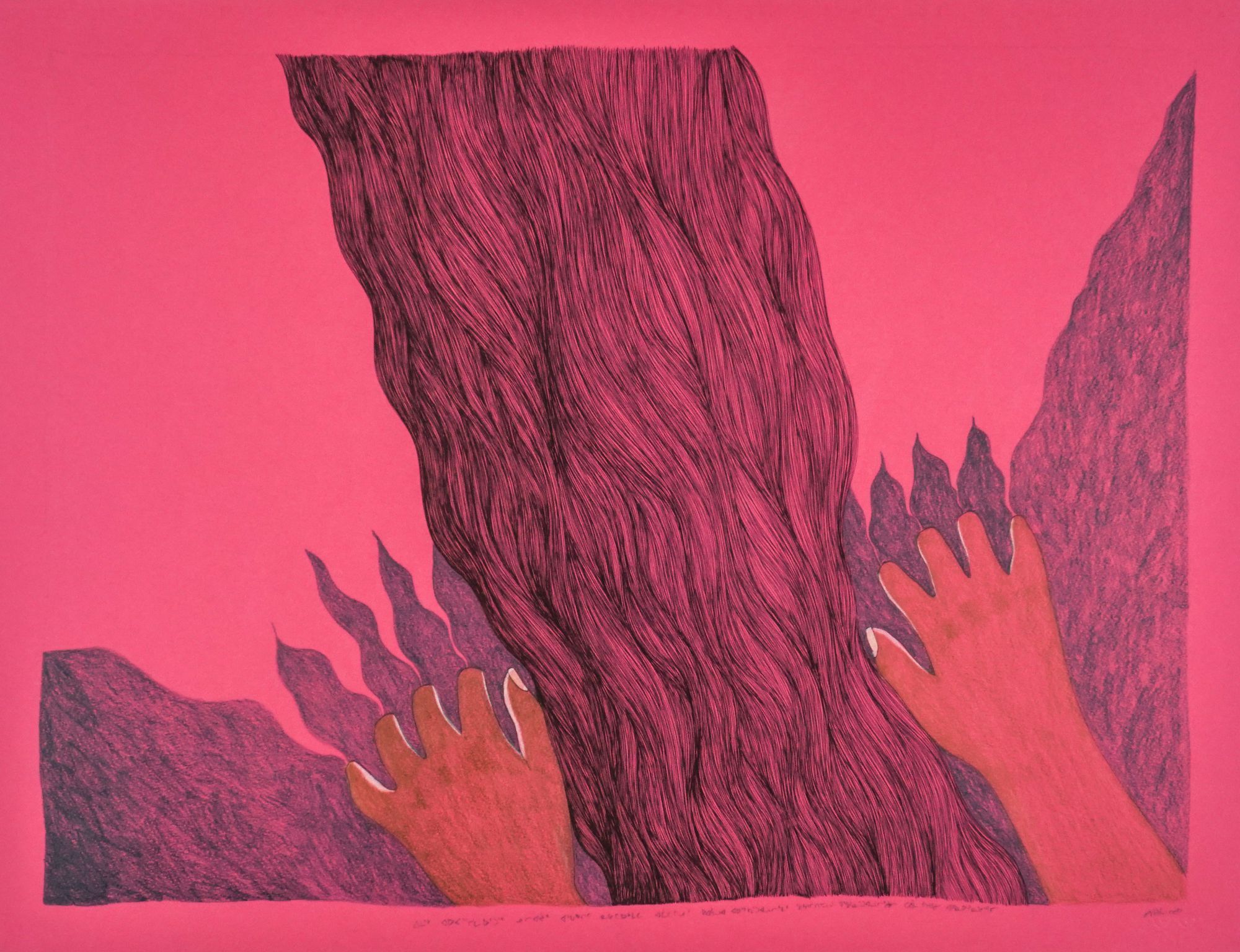

Composition (Sedna’s Hands) by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), colored pencil & ink, 20” x 25.5” (2009). Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto

Ningiukulu Teevee always has an unusual take on any subject she explores. This is especially true with regard to Sedna. One of her her strangest creations is Sedna’s Hands, another work in which the subject is barely seen. Most artists usually focus on Sedna’s body and hair and avoid dealing with her hands, which is the violent and bloody part of her story. Ever the iconoclast, in Sedna’s Hands Ningiukulu Teevee makes the goddess’s hands the focal point of the drawing. Adding to the impact is the artist’s use of the color red, suggesting blood, which seems to permeate the piece. The goddess’s hands appear to be attempting to stroke her hair, but the missing fingers prevent her from doing so. Although visually powerful, Sedna’s Hands may not be to everyone’s liking.

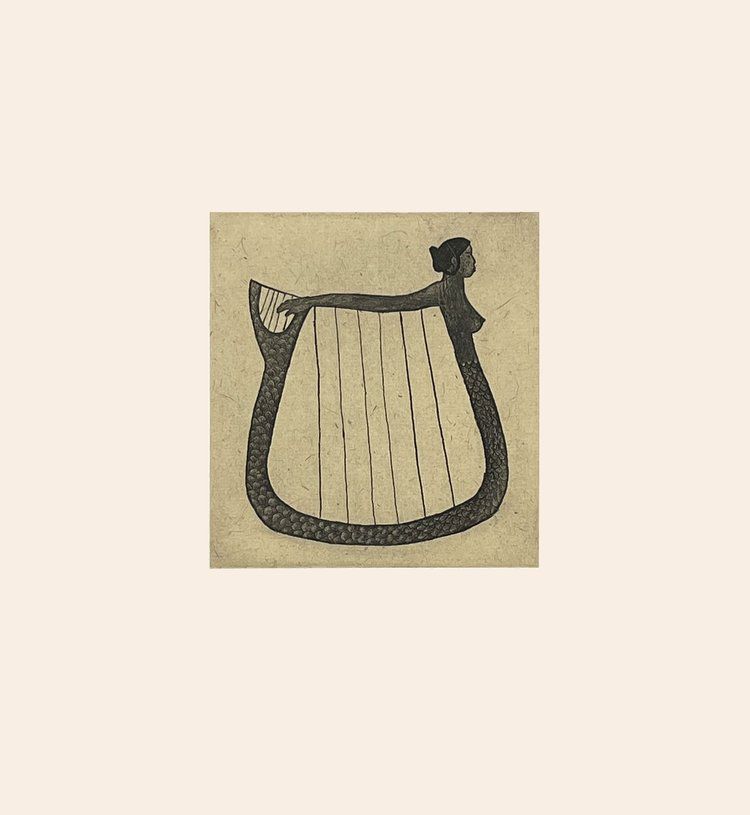

Sedna’s Song by Ningiukulu Teevee, Kinngait, (Cape Dorset), etching and chine collé, 11 3/4” x 10 3/8” (2019). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Image courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto and Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto.

In Sedna’s Song, Ningiukulu Teevee once again gives the viewer her personal spin on the Sedna myth. Despite the work’s title, the goddess does not actually make an appearance. Instead, the focus of the piece is the musical instrument that the shaman or members of the community might use to accompany the songs they sing to placate Sedna. Always fanciful, Ningiukulu Teevee employs the image of a harp, an unusual one at that. However, this is not a traditional Inuit instrument. Instead, the main instruments used by the Inuit were drums, rattles, and sometimes bullroarers. With the arrival of Nordic, Scottish, and Irish explorers and sailors in the 16th and 17th centuries, other instruments, such as the mouth harp and zither, were introduced, and later the accordion and fiddle were added as well. Nigiukulu Teevee’s choice of a harp for her print may have been influenced by her exposure to other cultures, but she has made it distinctly her own. Within the larger harp, on the upper left side of the harp is what appears to be a smaller one, and on the upper right side of the instrument is bare breasted torso of a woman who might, perhaps, be Sedna. This figure reaches her arm back to play the smaller of the two instruments. Sedna’s Harp is yet another Nigiukulu Teevee’s many interpretations of the Sedna myth.

Sedna has been presented in sculpture, prints, and drawings in many different ways, depending on how each artist views her. She has been portrayed as beautiful, angry, vengeful, petty, spiteful, and vein. Whether as protector, avenger, or seductress, Sedna continues to intrigue both artists and collectors, and there are images of her to please just about any artistic taste.