Collector's Corner

Two Old Women: An Alaskan Legend Of Betrayal, Courage And Survival: A Teacher’s Perspective

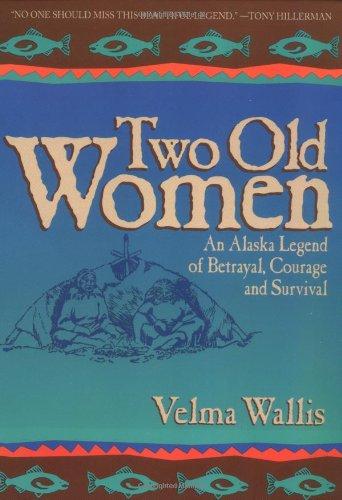

It is hard to believe that it has been just over twenty years since I first stumbled upon Two Old Women by Velma Wallis while I was visiting Fort Yukon, Alaska, the author’s hometown. At the time, I was still teaching and looking for books that I could use with my English classes. The fact that the book was short, only 120 pages, immediately caught my attention. For my students, asking them to read even five pages a night was tantamount to torture. I taught the most educationally lacking students in the school, which is not to say they weren’t smart. Their reading, spelling, and grammar may have been below grade level but they were, nonetheless, extremely intelligent. I also knew that another selling point was that the book was beautifully illustrated by Native artist Jim Grant. Whenever I handed out a new novel in class someone invariably would ask, “Does it have pictures?”

After reading Two Old Women, I knew that my students could draw many valuable lessons from it. When other teachers in my department learned that I was teaching a book about two elderly woman who were also Athabaskan Indians to my senior classes they were skeptical to say the least. The students in our school were overwhelmingly African-American, though we did have a smattering of hispanics as well. The other teachers felt that “our students,” most of whom had grown up in our mid-size city located in New York State just seventeen miles north of Manhattan, wouldn’t be able to relate to such a book. I disagreed. Having read Two Old Women, I knew that, despite superficial differences, it’s themes are universal. My teaching philosophy has always been that if a work of literature was about the human condition then anyone should be able to identify with it and that it is the teacher’s job to point out our common humanity.

As soon as I handed out the books, I was met with the reaction that I had anticipated: “This book is boring” (of course, the students hadn’t read even one word of the book yet, which was par for the course) and “Why are you making us read a book about old people?”

I explained that the book wasn’t really just about old people but about all people. Then, I made it personal. I asked my students if they had elderly people in their families, who they were, and how they felt about them. In spite of some complaints about old people sometimes being difficult, my students revealed how much they loved their grandparents and even aunts and uncles and spoke about their relationships with them. Of course, we also spoke about young people and how difficult they can sometimes be.

Most of my students had difficulty reading and, based on experience, I knew that if I assigned even a few pages to be read each night the majority of my students wouldn’t do it. Instead, I started to read the book out loud to each class, stopping to ask questions and explain various points. I also discovered that many of my students had never had someone read to them. I next asked for volunteers and each day more and more students were willing to read in class. They knew that, although I would gently correct a mistake, no one would make fun of them. Each day, I could see my students becoming more and more involved with the book.

Set in the pre-contact era, Two Old Women tells the story of eighty year old Ch’idzigyaak and seventy-five year old Sa’ who are left behind by the People who are starving. The two friends had become dependent on the younger members of their band to supply them with all that they needed and had ceased contributing to the welfare of the group. In order for the rest of the People to survive, the Chief makes the terrible and rare decision to leave the two old ones behind. No one, including Ch’idzigyaak’s daughter Ozhii Nelli, raises a voice in protest. However, she does leave the two women a bundle of babiche, untanned moose hide string. Shruh Zhuu, Ch’idzigyaak’s grandson, also secretly leaves the women his hatchet before the tribe moves on. The two elderly women, at first, sit in silent disbelief. Then, Sa’ says, “They forget that we, too, have earned the right to live! So I say if we are going to die, my friend, let us die trying, not sitting.” In a sense, “Let us die trying, not sitting” becomes the book’s rallying cry.

Using the hatchet that Shruh Zhuu had left behing, Sa’ kills a squirrel. The two women boil the meat, save it, but drink the broth. They also set rabbit traps and, later, use the babiche that they had been given to make snow shoes. The women are once again doing all the things that they and everyone else thought they were no longer capable of doing. Remembering a place where resources were once plentiful, the two women decide to make the arduous journey to the old camp. On their journey they face many challenges and endure numerous hardships. Yet, by their ingenuity and by remembering long forgotten skills, they not only survive but thrive. During the course of their time together, the two women, who had previously barely known one another, become friends.

In the course of their year away from the tribe each woman tells her story. Sa’ explains that in her youth she rebelled against The People by hunting and trapping like a man and that this was not the first time she had been left behind. When she defied the chief by defending an old woman who was going to be abandoned, her punishment was to be left behind with her. Sa’ eventually found a man and fell in love with him.

Ch’idzigyaak divulges that in her youth her grandmother had been left behind because she could no longer walk and the People, who were starving, had to move on. She also reveals that her brothers returned, killed the old woman, and burned her body so it would not be eaten. Ch’idzigyaak also indicates that, unlike Sa’, her marriage was arranged by her family.

The women build a shelter, kill muskrats and rabbits, collect berries, catch and smoke fish, and use the fur of the animals they have caught to make clothing – much more than they need. All this had to be accomplished before the darkness and desolation of the northern winter set in so as to prevent starvation.

The following winter the People return to the area where they had left the two old women to die but, because no trace of them can be found, the Chief believes that they must somehow have survived. He sends out an old tracker named Daagoo with two younger men to find the women, believing that if they are alive it will give his starving people renewed hope. The three men set out and before long Daagoo picks up the scent of smoke, which eventually leads them to the women’s camp. Mistrustful at first, Ch’idzigyaak and Sa’ eventually realize that Daagoo is an honest man and they agree to dole out rations to the People. After some time the two women are reunited with those who had abandoned them and Ch’idzigyaak is reconciled with her daughter and grandson.

Although Two Old Women contains many universal themes, in a broader sense, the book allowed me to introduce other subjects as well, becoming a springboard for discussions about Native American culture, history, and art. I brought in pieces from my collection and students who had never participated in class raised a hand to ask a question or make a comment. Over the years, I discovered that the majority of my students enjoyed Two Old Women and found reading it a memorable experience. It is a book that I constantly recommend, most recently to the head of one of the most prestigious private schools in Manhattan. For a minimal amount of effort, Two Old Women offers a maximum of reading pleasure.

Other books by Velma Wallis:

Bird Girl and the Man Who Followed the Sun

Raising Ourselves: A Gwich’in Coming of Age Story from the Yukon River