Collector's Corner

BACK TO THE FUTURE: IAIA Student Artists of Note – Part 1

Sometimes in order to go forward it is necessary to go backward. This is especially true for artists who, for inspiration, often turn to earlier artistic forms, such as ledger art, or to a time in life that was particularly painful or fraught with struggles. In addition, contemporary Native American artists are also using a variety of media to examine social and political issues as well as to express their deepest feelings about all they are experiencing in the 21st century. At first, many collectors were reluctant to embrace such work. “Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation,” three groundbreaking exhibitions, curated by Ellen Taubman and David McFadden, brought about change by presenting the best examples of contemporary Native art, enlightening museum-goers, scores of which were collectors, as well as empowering many other Native artists to experiment with non-traditional media and materials, to approach traditional forms in new and unique ways and to explore controversial subject matter. Such ideas are supported and fostered by the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts and the Institute of American Indian Arts. On a recent visit to IAIA, I was invited to view “A Tribute to the Mentors,” an exhibit of student art. I was greatly impressed, particularly by the work of Justus Benally, Terrance Clifford, Shaun Beyale and Terran Last Gun.

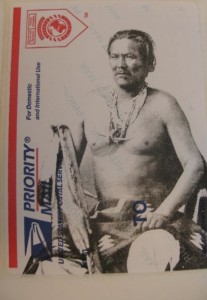

Manuelito by Justus Benally, San Carlos Apache, print on ledger, priority mail note, 3.5”w x 5’h (2014).

Burden Basket by Justus Benally, San Carlos Apache, print on ledger, priority mail note, 3.5”w x 5’h (2014).

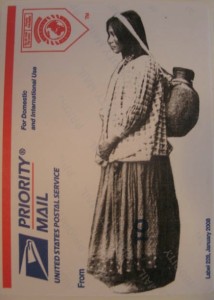

Bless It Well (aka Water Carrier) by Justus Benally, San Carlos Apache, print on ledger, priority mail note, 3.5”w x 5’h (2014).

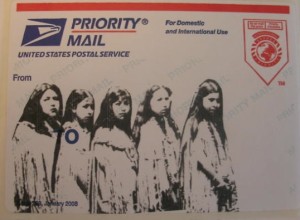

Exiled by Justus Benally, San Carlos Apache, print on ledger, priority mail note, 3.5”w x 5’h (2013).

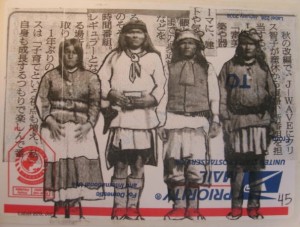

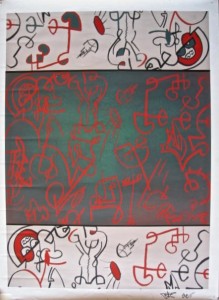

Mixed Media Renegade by Justus Benally, San Carlos Apache, print on ledger, priority mail note, 3.5”w x 5’h (2014).

Justus Benally’s series, though composed of small works, is quite powerful. Not only are the five pieces – Manuelito, Burden Basket, Water Carrier, Mixed Media Renegade and Exiled – a modernist take on historic ledger drawings, they also reference the Navajo Long Walk and, by extension, the relocation and mistreatment of Native People by the U.S. Government. The fact that one of the works in the group is titled Manuelito suggests this interpretation. The first chief to unite all of the Navajo clans, Manuelito and his warriors fought against efforts by the Federal Government to remove the Navajo by force from their ancestral lands in eastern Arizona. Finally defeated by the U.S. Army, Manuelito and his people were forced at gunpoint to walk up to thirteen miles a day until they reached Bosque Redondo in western New Mexico. Between 1864 and 1866 there were over fifty such marches that were 300-450 miles long, depending on the route. The suffering of the Navajo people was unspeakable. Many died along the way; some were simply shot. The clothing of the figures in the other works indicate that they are most probably Apache. Along with the Navajo, many Chiricahua Apaches were among those compelled to make the arduous walk to Bosque Redondo. They were also exiled by the U. S. Government via railroad and government rail trains. In addition, some Apache men, including Geronimo, were sent to Florida where they were imprisoned at Fort Pickens and Fort Marion. However, there were groups of Apaches, referred to as renegades, who migrated to northern Mexico where they continued to wage warfare with the U.S. and Mexican Governments until 1924. Mixed Media Renegade references the treatment of Apaches. According to Mr. Benally, “This work was created while studying under Linda Lomaheftewa. It was originally a 4”x 5” hand created image in which I juxtaposed traditional Japanese text concerning warfare with four apache people. In the center is Chief Naiche, to the left is his wife, to the right are two warriors who are dressed with ammunition belts weighed down and adorned in the finest garb they could acquire” In an Email interview, the artist went on to say, “I have been inspired by the truth of history, the misconceptions about Indigenous people of North and South America and the genocide which has a continuing role in this society today.” He then went on to speak specifically about his art: “In the late summer of 2013 fellow artist Amanda Beardsley proposed a new technique which enabled us to created templates in order to hand print onto priority mail documents. I had introduced her to a form of sticker art and in return she introduced me to manually producing each one of a kind print.” He then added, “when I think of the shipping labels I am inspired by the blank industrial canvas made of paper, adhesive, and some kind of waxed backing. As a kid I would go and collect as many stickers as I could in order to paint them for street art warfare, which is the culture they are from which they are derived – Sticker Bombing.

My Innermost Feelings by Terrance Clifford, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, mixed media: charcoal/photograph/PhotoShop on paper, 10“w x 30“h (June, 2011). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Rather than drawing on historical events, Terrance Clifford’s My Innermost Feelings was inspired by deep emotional experiences. According to the artist, this work “. . . started out as a charcoal on paper, then I took a photo of the piece and uploaded it to photo shop where I edited it with color.” Mr. Clifford took his inspiration from a childhood memory – a trip to San Diego with his grandfather, father and sister. “I was only five years old,” he remembered. “During the trip I remember driving into the sunsets and seeing the silhouettes of the mountains and the open desert road. The feelings I had of seeing all these totally new things were so touching for me even at my very young age.” The artist added that his feelings were of happiness, pain, lonesomeness, wonder and more. “These feelings,” he added, “have always been with me since I can remember and as I grow as a person I begin to understand them more and more. I feel as if I have successfully put those feelings into this piece.”

My Innermost Feelings is a decidedly abstract work that pulls the viewer in because of its emotional intensity. “While the art was flowing out of me . . . I felt my conscious self drift away into my memories,” the artist stated, “and something else inside me appeared . . . . Suddenly I felt my arms moving. Before long I opened my eyes and I saw a lifetime of memories all put onto the paper.”

Inner Demon by Shaun Beyale, Dine, etched and glazed ceramic tile, 5.5”w x 8“h (2007). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Although he is becoming known for his striking drawings and prints, in 2007 Shaun Beyale produced a group of graphically bold and, because of the subject, potentially controversial ceramic tiles. These haunting and surreal works represent a time of profound difficulty in the artist’s life. Together, Inner Demon, Party Tree and Moonshine Baby evoke a sense of struggle that is palpable. By creating black tiles with the imagery etched into them, Mr. Beyale created a tone of deep anguish. “Inner Demon,” the artist stated in an Email interview, “was about how I felt, like I had an inner demon when it came to alcohol. When it came to drinking, I seemed to lose control and drink too much until I would blackout. So the male in the foreground is me and the background was to represent my home, the Navajo Nation, and the figure floating above was how I would feel. I felt helpless at times and felt like I was drowning, not only with alcohol but also feeling depressed. I felt like a stereotype at times, the drunken Indian, so that’s why I had the figure on top look ‘stereotypical Indian-like,’ with long straight hair, which I don’t have.”

Moonshine Baby by Shaun Beyale, Dine, etched and glazed ceramic tile, 4.5”w x 5.5“h (2007). Collection of E. J. Guarino

“Moonshine Baby,” Mr. Beyale added, “is about my addiction to alcohol. I felt at times that I was hooked into alcohol like a machine hooks up to a patient at the hospital. It also represents how many feel, that on the reservation drinking is all they know and all they look forward to. So I chose to use a full grown man in a fetal position connected to a moonshine bottle to represent a nation hooked on alcohol. I feel that by showing these images it will raise questions in the audience and make them aware of situations many face on the Rez. I wish to show and talk about the problems of alcoholism and to show that many face these problems and that alcoholism can be fought and overcome.”

Party Tree by Shaun Beyale, Dine, etched and glazed ceramic tile, 8“w x 6“h (2007). Collection of Jeff VanDyke

“Party Tree was about home and how me, my cousins and friends would party out in the Rez,” the artist continued. “We had spots all over the place but there was one particular tree we would hangout at. The tree was surrounded by broken bottles and trash. We’d party all night and just be crazy. So, in the very foreground is me, lying on the ground in either a drunken stupor or blacked out. The figure by the tree represents . . . the ‘alcohol demon’ and his influence on me. Many times I have woken up by the tree, hung over and feeling bad about my life at the time. I am glad to have overcome that period in my life and this tile piece helped me in my healing process.” It was very brave of Mr. Beyale to take on the subject of alcoholism since Native Americans, males in particular, have so often been stereotyped as drunks.

Puff Balls by Terran Last Gun, Piikani (Blackfeet), screen print on handmade bark paper, 12” x 16” (2014).

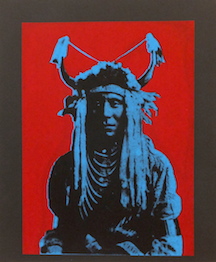

I AM Piikini by Terran Last Gun, Piikani (Blackfeet), screen print on black paper with red background, 10” x 12” (2014).

Sometimes what first appears to be a representational work, upon reflection, turns out to be more complex. In Puff Balls and I AM Piikani, two screen prints by Terran Last Gun, the artist reproduced the image of a Piikani man, circa 1909, wearing a traditional split horn headdress. In an Email interview, I asked Mr. Last Gun about the unusual title Puff Balls and he explained that “. . . the four triangles are the symbol for mountains and the circles inside them . . . represent stars or . . . fallen stars people call dusty stars. There is a plant that grows up near the mountains called puff balls, that is what they say is the fallen star. The triangle and circle image is seen on our painted lodges at the bottom and is unique to my tribe. I titled it for that reason.” Although the artist used the same historic image in I AM Piikani, the work is completely different from Puff Balls. In creating a blue figure against a red background, Mr. Last Gun produced a bold work, reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s screen prints of celebrities. However, I Am Piikani makes a defiant statement about individual and group identity.

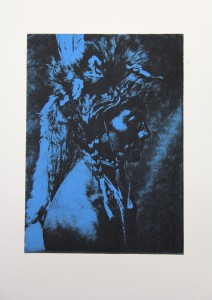

Untitled by Terran Last Gun, Piikani (Blackfeet), KM photopolymer plate with blue roll over, 7.5” x 10” (2014).

In an untitled work, the artist once again employs an historic image, a photograph of a Piikani man named Yellow Kidney which was taken circa 1910. The use of a blue roll over on the print creates a tone of deep melancholy, a subtle commentary on the history of Native peoples. “I like how in this image,” Mr. Last Gun stated, “the man is wearing a fox hat, which is uncommon today within my tribe.”

Untitled by Terran Last Gun, Piikani, (Blackfeet), monoprint, 15” x 22” (2014).

Another striking print by Mr. Last Gun abstracts the figure of a Native American. In this untitled work, a black spirit-like figure with a feather in it’s head seems to float on the white background which gives this monoprint an otherworldly quality. The artist noted that “. . . the figure or symbol is seen throughout some Piikani lodges and even in petroglyphs and pictographs my ancestors made though it is more geometric looking . . . .” About his work, the artist commented that it “. . . reflects my identity and culture as a Piikani person; I am a proud citizen of my tribe. There is a lot of Piikani symbolism in my work, but with a contemporary look. I consider myself to be a modern Indian expressing what I see and go through as a Native by communicating that throughout my art.” As a collector, I find it exhilarating that so many Native artists are taking risks to create works that challenge outmoded notions of what constitutes Native art. A number of artists, such as Jody Folwell, were in the vanguard of this movement. However, it is doubtful wether many other artists would have felt empowered to do the same without the three “Changing Hands” exhibits. Institutions like MoCNA and IAIA continue to foster experimentation by encouraging artists to take inspiration from wherever they may find it. As a college, IAIA offers classes in a variety of media – some traditional, some non-traditional – and also supports the work of student artists through exhibitions of their work. “A Tribute to the Mentors,” for example, allowed me to experience and collect the art of Justus Benally, Terrance Clifford and Shaun Beyale, each of whom created powerful and unique works. I feel privileged to have them in my collection.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Andrea Hanley for her invaluable help with this article.