Collector's Corner

A BARTOW BESTIARY: The Animal Kingdom in Rick Bartow’s Works on Paper

Since ancient times and across cultures, animals have often been used to represent human characteristics in art and literature. From Aesop’s Fables, The Fables of La Fontaine, countless children’s stories, and George Orwell’s dark tale Animal Farm, animals have been used by artists as stand-ins for humans and all their vices and follies. Sometimes they even function as a type of self-portrait. Rick Bartow’s prints of animals are part of this long-standing tradition.

Rick Bartow’s art is populated by a wide range of creatures – bears, coyotes, donkeys, dogs, a cat, wolves, a pig, a mouse, a rat, eagles, hawks, crows, ravens, sparrows, jays, kestrels, frogs, a snake, beetles, cicadas, a fly, a bass, a flounder, salmon, and even a monkey. The entire Animal Kingdom – mammal, bird, fish, amphibian, reptile and insect – is represented, though some more than others. The myriad creatures that Bartow chose to portray serve an artistic purpose more complex than straightforward representation. They are frequently stand-ins for various aspects of the artist’s personality, but they always function on a symbolic and psychological level. In Bartow’s art things aren’t quite what they appear to be.

In the past seventeen years I have managed to add fifty-three works on paper, two sculptures, and a small painting by Rick Bartow to my collection. The various works cover a wide range of themes, many incorporating images of animals. Strangely, if someone were to ask me if I liked artworks portraying animals my first impulse would be to say that I don’t. However, that would not be true. Although I avoid overly sentimental representations of animals, depictions of various and sundry creatures have made their way into my collection, many of which were created by Rick Bartow. It’s a matter of my finding a work that piques my interest.

Tiny Hawk by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching on handmade Japanese paper, unique) 15” x 18.5,“ (2000). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo Courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Ironically, it was not the small bird that attracted me to Tiny Hawk, but rather it was the fact that the image was produced on a torn page that was actually a letter that had been sent to Rick Bartow. According to Wilder Schmaltz, Assistant Director of the Froelick Gallery, “The plate is printed on an irregular piece of handmade paper on which a letter to Rick from Naoaki Sakamoto is written. He is the proprietor of Paper Nao, the Tokyo paper shop that supplied Rick and his print collaborator, Seiichi Hiroshima (and countless other artists) with incredible papers for prints and drawings over the years.” The undated letter is fairly mundane: Nao-san asks to meet with Rick Bartow, his wife Julie and his son Booker. “. . . the print was made the year after Julie’s death in 1999,” Wilder Schmaltz added, “and a subsequent period of artistic silence of about a year from Rick. This proximity to such personal devastation may account for the dark slashing line . . . .”

It is typical of Rick Bartow’s art that he would take something as prosaic as a letter from a friend and turn it into a work of art. “Rick clearly took time and care with this refined line work,” Wilder Schmaltz said in an email, “all of the fine marks he scratched into the copper are so suggestive of various feather textures, along with the horizontal lines in the background – it’s interesting to contrast works like this with some of his more visceral representations of birds . . . . He seems to have added additional outlines to the wing fairly late in the process, changing his mind about the shape he needed. The dark black slashing mark from the upper left, which has appeared in a number of works as a dramatic striking away – a traumatic loss, often death or blindness, that results in some greater perception or insight . . . . Here, it may indicate the motion of the wing, or it may also be related to his dissatisfaction with the way he’d initially represented the wing ( . . . he often made his edits apparent in his work, asking the viewer to imagine what it would look like if he’d made it more like this}.”

Rick Bartow often took what he found and turned it into art. He would often glues pieces of paper together to create a larger area to fill and often used ephemera such as used envelops as his canvas. As an artist, nothing was out of bounds for him, even a letter with sections of the paper missing.

Salmon by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, 15” x 31.5”, #4/10 (2003). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo Courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR

I was first attracted to Salmon because of its size. I first saw Rick Bartow’s renderings of these fish as part of his Autumnal Metaphor Series, which contains two monumental works portraying these creatures. Those large works on paper were beyond my range financially, but they fascinated me. The dimensions of Salmon are unusual. Drypoint etchings are generally not produced on such a large scale. Beyond that, the quality of the work is astonishing.

Although the tail fin is clearly defined, the dorsal, pectoral, pelvic, and anal fins are delineated by slash marks. The dorsal fin is drawn in such a way that it looks very much like Bartow’s signature spiky hairstyle that he had throughout much of his career. (See below.).

Self 00 by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint/etching, 6/10, paper size: 8”w x 11.5”h; image size: 1.5”w x 2.5”h (2000). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo Courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

The image of a salmon appears frequently in the artist’s work. Bartow used a variety of animals as a sort of stand-in for himself. Different creatures represented various aspects of his personality and became, in essence, symbolic self-portraits.

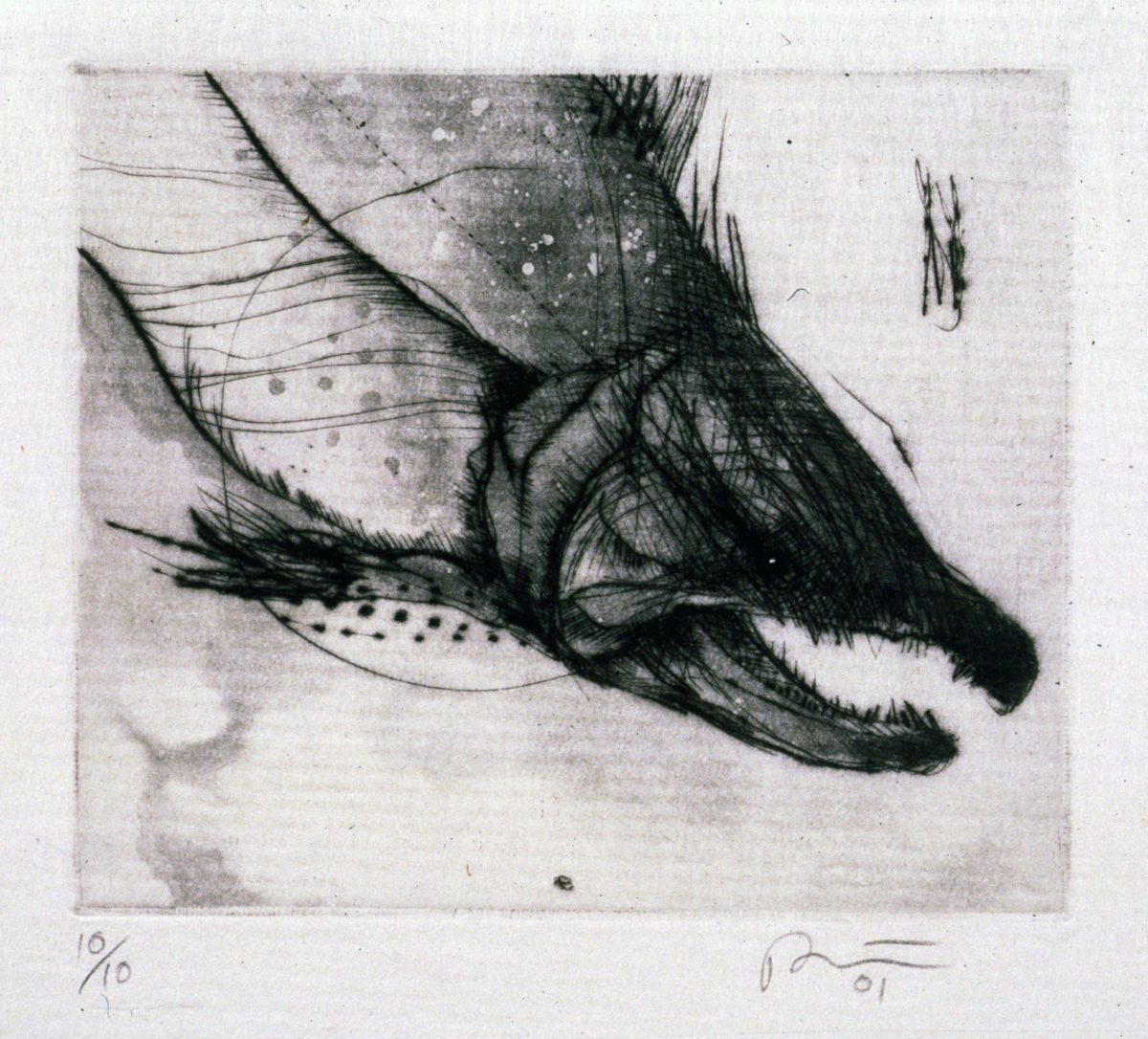

Twernish by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, (#10/10) 13” x 9” (2001). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

In the Yurok language twerr-nee’sh means spawning salmon. Bartow used a variant spelling of the word for his print in which the fish looks somewhat aggressive. Over the salmon is a circle containing dots, which may represent eggs. The paper is mottled, giving the impression of murky water, and in the upper righthand side of the page there is a curious mark that looks very much like a capital M. Like many marks the artist placed on his works on paper, it is an enigma.

Salmon were an important symbol for Rick Bartow because of their struggle to create something that would live beyond themselves. In these creatures he most likely saw a metaphor for the artist’s existence.

Flounder by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, (#3/20),13” x 10” (2000). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

At first, the choice of a flounder with googly eyes seemed an odd choice for Rick Bartow. Why would he choose this particular fish as the subject of a print? I could understand his many salmon prints because of the amazing transformation salmon undergo, but it took some contemplation and research to understand Bartow’s artistic decisions with regard to Flounder. I eventually remembered that flounders, like salmon, go through their own type of transformation, a theme that Rick Bartow frequently explored.

In it’s larval state a flounder has one eye on each side of its head just like other fish. As it grows, one eye migrates to the other side of its body, resulting in both eyes being on one side, which faces up. After going through this metamorphosis, the flounder lies on the bottom of the ocean, which camouflages it from both predators and prey.

Once again, the artist seems to be using a humble fish to represent the many changes faced in the course of a lifetime, particularly his own.

From Japan by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching on handmade Japanese paper, 18” x 12,” Edition: #19/20, (2000). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo Courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

Early on in Japan monkeys were seen as mediators between humans and gods. Later, they came to represent the trickster as well as people considered undesirable. Later still, these humanlike creatures became metaphors for human shortcomings and also represented people who foolishly emulate others. In From Japan, Rick Bartow personifies the monkey in his drypoint etching by giving him human characteristics: a bandana, spectacles, clothing and, perhaps, a paintbrush in his hand. The image is most likely another of the artist’s self-portraits. Ever the trickster, Bartow portrays the monkey with hair similar to his own spiky hairstyle, has him wear his trademark spectacles on a large nose similar to his own, and portrays him holding what appears to be an artist’s tool. Finally, the monkey is wearing a star spangled headband not unlike the one Bartow is wearing in Headband, a 2001 self-portrait (see below). From Japan is one of many examples of the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints on Bartow’s art.

Headband by Rick Bartow, 01, drypoint etching, (#20/20), 12” x 9” (2001). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photo Courtesy of the Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR.

In one of his emails to me, Charles Froelick said of my collecting that it was “methodical, strategic and thoughtfully meandering.” I certainly can’t quarrel with that, especially the “thoughtfully meandering” part. My tastes do tend to be eclectic. Since I became aware of Rick Bartow’s work in 2003, as part of Continuum: 12 Artists at the National Museum of the American Indian in Manhattan, I have been fascinated (though some might say obsessed) by Bartow’s art, particularly his prints. Each time I look through the many works on paper he created, in person at the Froelick Gallery or online, I always uncover a new and exciting aspect of the artist’s work. Whether I am exploring the influence of Ukiyo-E, the function of mark making, the symbolic use of animals, or portraits and self-portraits, Bartow’s art is a well that apparently has no bottom and, as a collector, it is something for which I continue to be grateful.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Charles Froelick, owner of the Froelick Gallery, and to Wilder Schmaltz, Assistant Director of the Froelick Gallery, for their invaluable help with this article.