Collector's Corner

COLORED WITH HUMOR: The Graphic Art of Ningiukulu Teevee

Known for her strong visual style, her powerful use of color, and her distinctive sense of humor, as well as her talent for presenting traditional aspects of Inuit culture in a unique way, Ningiukulu Teevee is one of Cape Dorset’s rising stars Hers is a decidedly contemporary sensibility and there is no other Inuit graphic artist who produces imagery quite like hers.

Auvviq (Caterpillar) by Ningiukulu Teevee, lithograph, 8/30, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 4”h x 5”w, Cape Dorset Spring Release #8 (2010). Photo courtesy of Arctic Artistry Gallery and Dorset Fine Arts. Collection of E. J. Guarino

I first became aware of Ningiukulu’s work in 2010 when Elaine Blechman, owner of the Arctic Artistry Gallery in Chappaqua, New York, gave me the artist’s Auvviq (Caterpillar) as a gift. It is one of the smallest Inuit prints ever to be produced. Creating a print on such a tiny scale was quite daring since most Inuit prints are much larger, a few even oversized. The dimensions of this work combined with the handling of the subject matter gives the piece charm and whimsy. The fact that it is hard to tell which is the creature’s front side and which its opposite end, creates the print’s gentle humor. The tiny leaf may be a clue, however. The caterpillar, shown not much bigger than life size, is a creature most might overlook. However, the artist uses the dimensions of the print to draw viewers closer, forcing us to consider this most marvelous of creatures, which will transform into a butterfly.

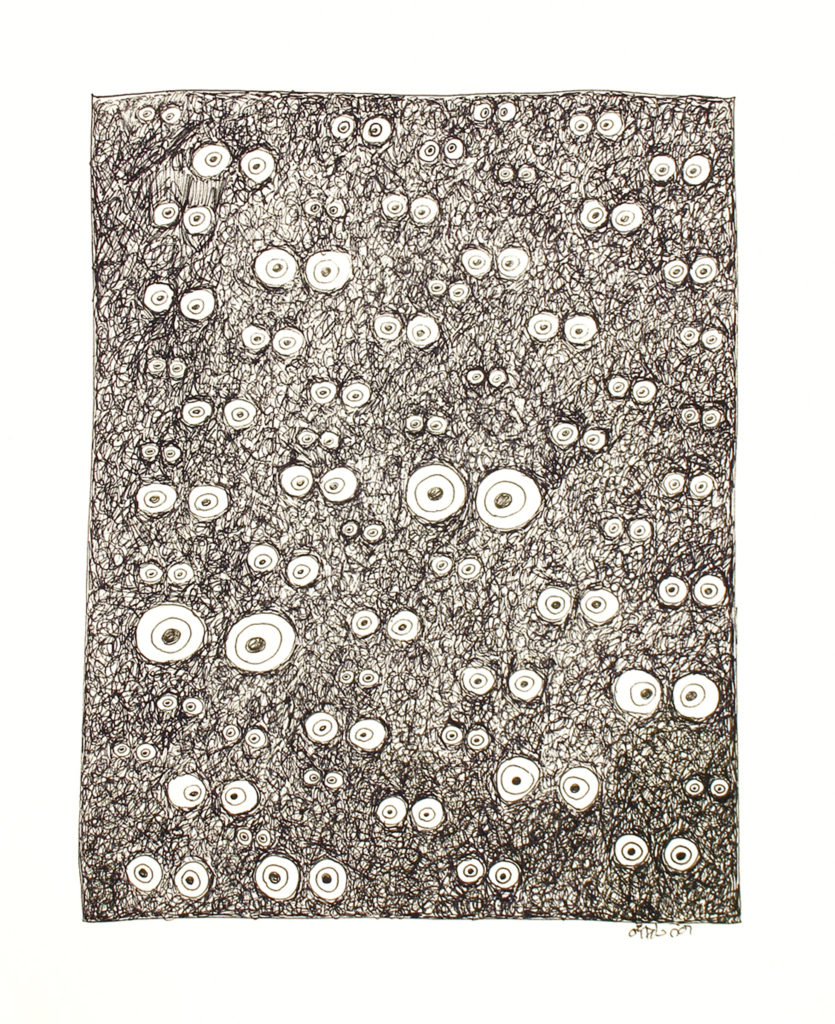

Many Eyes by Ningiukulu Teevee, ink, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 16” x 13” (2005/06). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts. Collection of E. J. Guarino

Many Eyes is an unconventional drawing with scores of eyes in varying sizes staring back at the viewer. The humor of the piece is disconcerting since it makes us wonder who or what, for that matter, is looking back at us. The use of multiple images, in this case eyes, has a powerful, hypnotic effect. It was something the artist was to use again, but for different effect in Rock Concert.

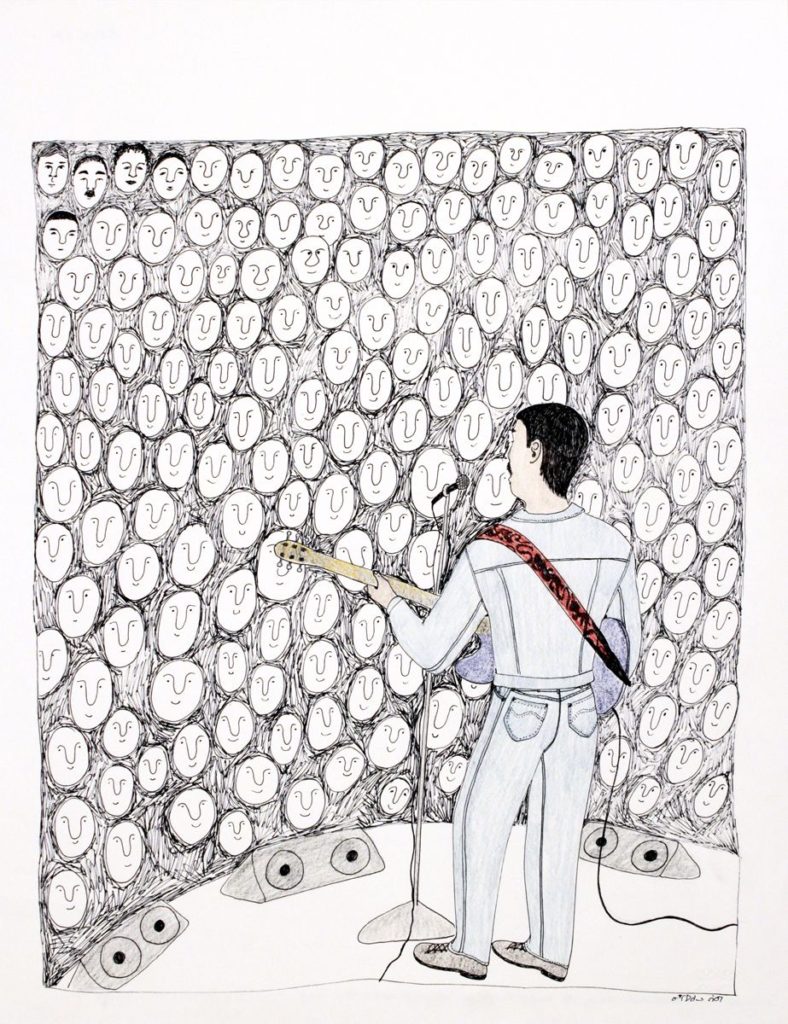

Rock Concert by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, pencil and pencil crayon, 26” x 20” (2005/06). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

Ningiukulu Teevee’s engagement with the world beyond the Arctic is obvious in Rock Concert. Scores of faces, all seemly the same, stare mesmerized at the performer in front of them whose back is to the viewer. Clearly, he is not what is important in the work. It is the audience, which has taken on a contemporary sameness. The artist’s use of color first draws the viewer’s eye to the musician, who is dressed in light blue, but then moves on to the multiple faces where it tends to remain. The humor of the piece is the fact that scores of people are willingly focused on one lone figure to the point that they become disembodied heads.

Marvelous Fan by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil and ink, 23” x 30” (2017). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

Marvelous Fan presents another aspect of fandom. It is a charming drawing that focuses on a young boy wearing a Superman cape, but he is clearly also a fan of his hometown since he is wearing a headband with Dorset emblazoned on it. Ningiukulu uses color to differentiate between the two figures who are riding on the back of a Skidoo. The child is holding on to an adult whose face the viewer does not see. The grown-up wears dark trousers and a white amauti, or parka, decorated with brown and blue stripes at the wrists and at the bottom. This person is most probably the boy’s mother. The young child is defined by a range of bold colors – black, blue, red, yellow, and flesh tone – that the artist has applied by pressing hard on the pencil crayon.

Through line and color, Ningiukulu defines the two figures she is presenting and, although the viewer never sees the vehicle they are riding, the activity in which they are engaged is obvious. In Marvelous Fan, the artist has created a work that is at once appealing and, most probably, a portrait of one of Cape Dorset’s residents. Of course, the piece could be pure fantasy, but since Ningiukulu so often draws from her hometown, it is more likely that the little boy she portrays is a real child that she knows.

Fashionista by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil and ink, 30” x 23” (2017). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

With her own characteristic brand of humor Ninguikulu Teevee documents life in her community. Though it is geographically removed from the rest of the world, Cape Dorset is connected and influenced via the Internet. Here, too, there are fashionistas who express themselves and separate themselves from others by means of their clothing choices. Through the strong color choices employed in Fashionista, the artist shows an aspect of Inuit life that is unknown to the outside world and she does it with a sense of amusement. The woman portrayed not only wears a stylish version of Arctic clothing, but sports an unusual hairstyle as well. The viewer also wonders what exactly is the woman wearing around her neck. It makes us wonder if there is nothing humans will not do, no matter how outlandish, to express their individuality? Once again, Ningiukulu captures our attention through humor and a striking use of color.

Eteqveluk by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil and ink, 30” x 23” (2017). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

The very first thing that intrigued me about Eteqveluk was the title. I wondered what it could mean. Since it had not been translated, I assumed that the word was a person’s name but, just to be sure, I Emailed Elyse Jacobson, one of the staff at Feheley Fine Arts, who wrote back, “You’ll love this, Eteqveluk means butt crack.”

Not only does Ningiukulu get us to chuckle over her title, but she also makes us wonder about the figure she has portrayed. Who is this person?. Is it a non-Inuit the artist encountered or an Inuit willing to expose his or her posterior for fashion even in the Arctic environment?

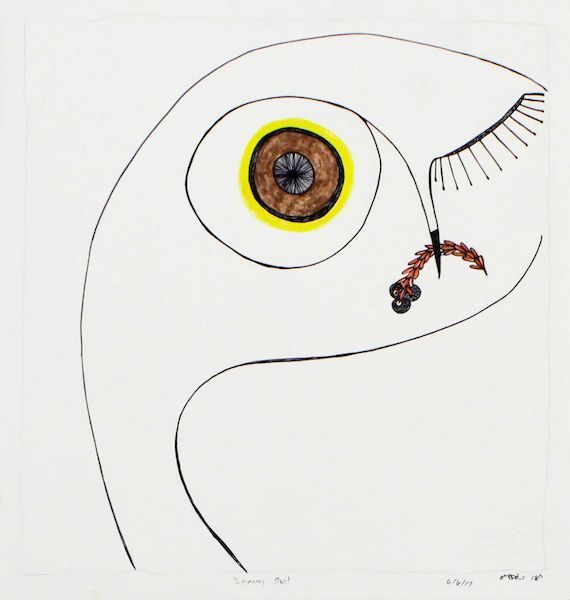

Sunny Owl by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil and ink, 12” x 11.5” (2017). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

Once again, the artist used heavy color to define the person she is depicting. However, the humor comes not only from the fact that the pants have slipped down, exposing what is usually kept covered, but the thong the person is wearing looks suspiciously like the images of owls Nigiukulu often draws. What is seen are eyes looking back at the viewer.

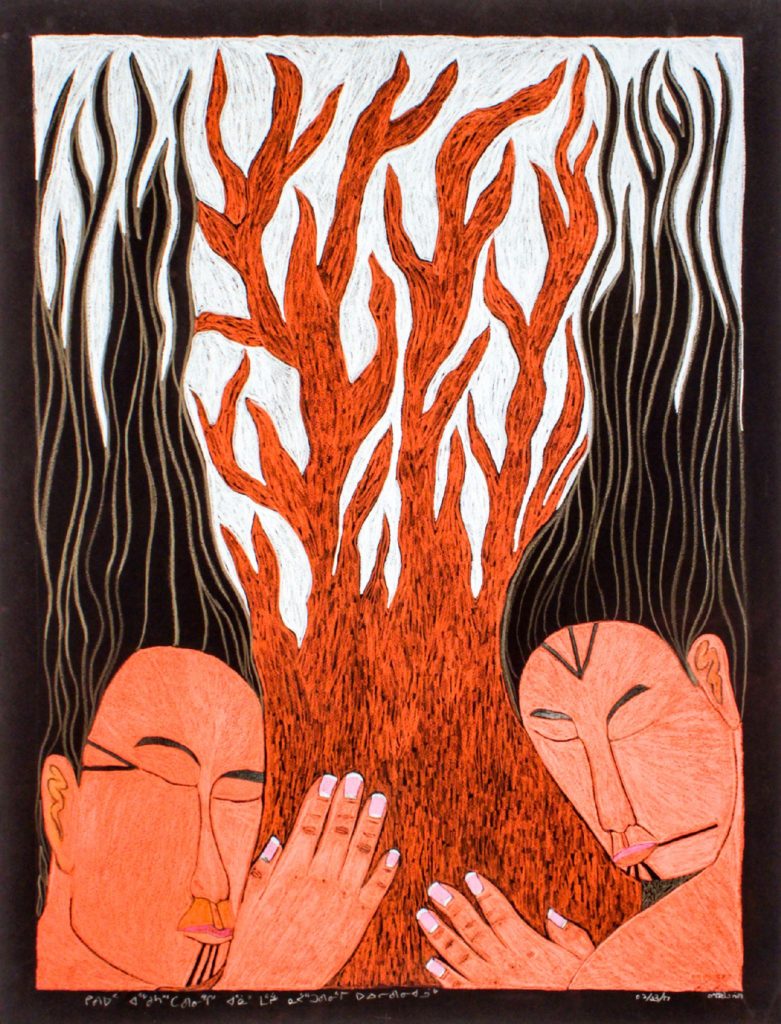

Kiviq Passes by Two Women by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil, 30” x 23” (2017). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

Nigiukulu Teevee is also noted for her idiosyncratic interpretations of traditional Inuit stories, which she often infuses with her unique brand of humor, giving them a modernist slant. In Kiviq Passes by Two Women, the artist presents one of the best known characters of Inuit lore. Kiviq (also spelled Kivioq, Keeveeok, or Qiviuq) is a legendary figure, on a par with Odysseus, in the epic stories of the Inuit. Like his Greek counterpart, Kiviq journeys far and wide, having many adventures, facing obstacles he has to overcome, and dealing with spirits, giants, cannibals, sea monsters, and other strange creatures. However, unlike Odysseus, Kiviq travels by kayak, dog sled, and sometimes he is borne by huge fish. He is also a shaman who can talk to animals, sing his way out of difficult situations, or transform into something other than a human.

It is hard to know to which Kiviq adventure Kiviq Passes by Two Women alludes. It appears that the hero has transformed either into seaweed or, based on color, coral. However, the image is ambiguous. It is unclear whether Kiviq has changed his form to elude the two women or, like Zeus, to seduce them.

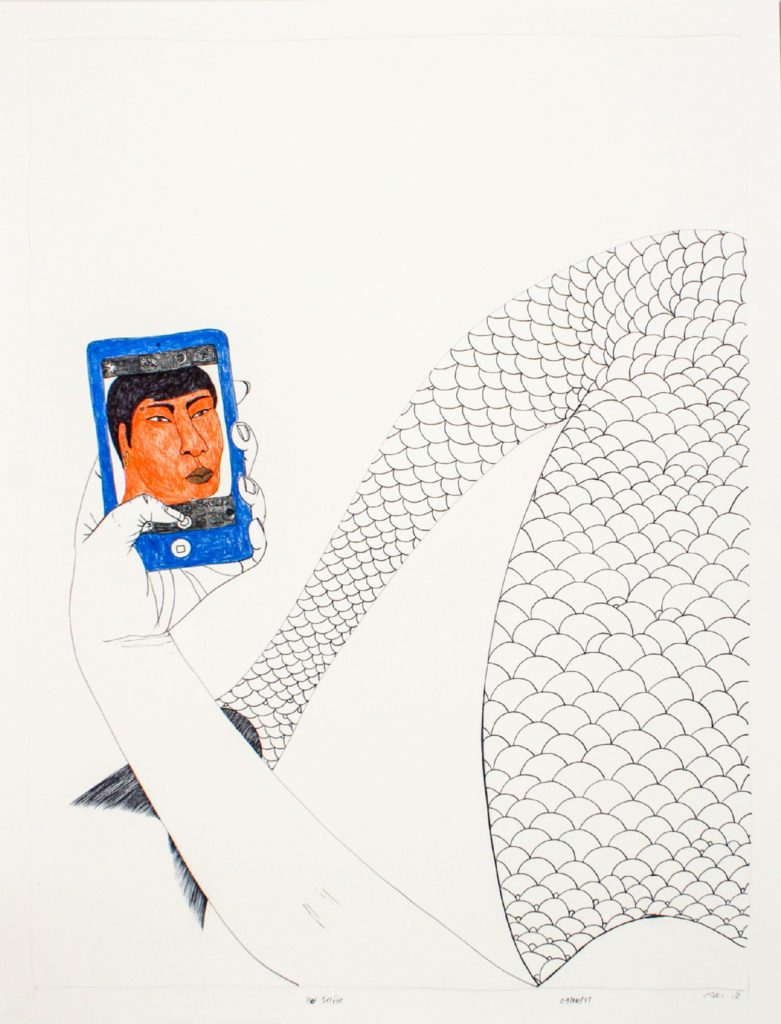

Her Selfie by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil, 30” x 23” (2017). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

Sedna, who is also known by a number of other names, is one of the most important goddesses in Inuit culture. Part woman, part fish, she most resembles a mermaid. It is she who controls the bounty of the sea. If angered, she can be vengeful, withholding the fish and sea mammals upon which the Inuit traditionally relied. There are many variations on Sedna’s story, but in each one her father takes her out to sea in his kayak, throws her overboard and, as she clings to the side of his vessel, he chops off her fingers and she sinks to the depths below. Contemporary Inuit artists generally portray the goddess minus the gory detail of her missing fingers and she is often presented as more playful than vindictive. Traditionally, hunters depended on the Sedna’s goodwill to release the creatures of the sea so that they could have success. If a taboo had been broken or the goddess had been disrespected in any way, she first had to be placated. It was believed that she held the fish and sea mammals in her hair and that, when angered, a shaman had to enter into a trance, visit her and appease her by listening to her complaints about the transgressions committed against her, singing to her, and combing her hair with a bone comb, an act that she could not perform herself. Appeased, Sedna would then set free all of the animals she had restrained.

In modern depictions, Sedna is often portrayed as vain. In Her Selfie, the viewer sees the goddess’s lower half and only sees Sedna’s face in her phone as she takes a photo of herself, reinforcing the idea that the goddess is narcissistic. The image of a deity taking a selfie is a decidedly contemporary concept and one that is inherently humorous. It also tends to humanize such beings, much the way the ancient Greeks did with their gods and goddesses.

The Shaman Turned to Rock by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil and ink, 23” x 30” (2016). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

Shamanism and transformation are important aspects of traditional Inuit belief and culture. Shamans were intermediaries between the physical world and the world of the gods and spirits. By going into a trance, they could enter the supernatural realm, a secret and dangerous place. Shamans, or angakkuit, in the Inuktitut language, could heal illnesses, appease deities who had been offended, and could transform into other forms, most often animals.

In The Shaman Turned to Rock Ninggiukulu presents the viewer with an unusual take on the theme: the shaman transforms into something non-living. Giving the subject a contemporary twist, the artist includes a vehicle moving up a road below the shaman as he turns to stone.

The title of the work also raises interesting questions. Since the word turned was used rather than transformed, it leaves one to wonder if the shaman changed himself to rock or if some malevolent spirit or god has done so.

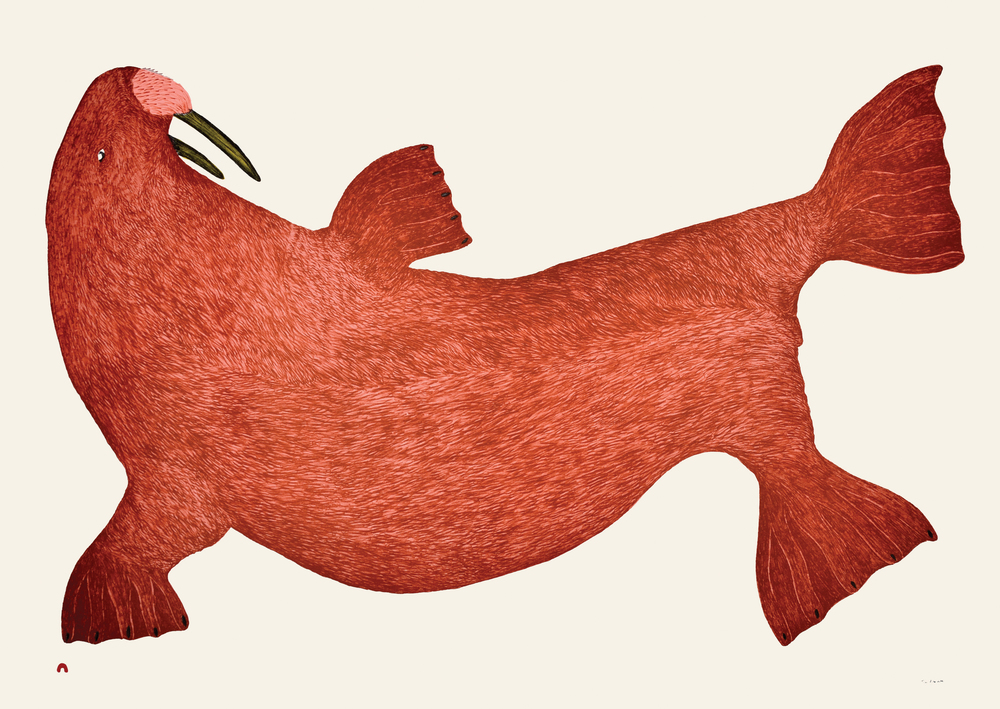

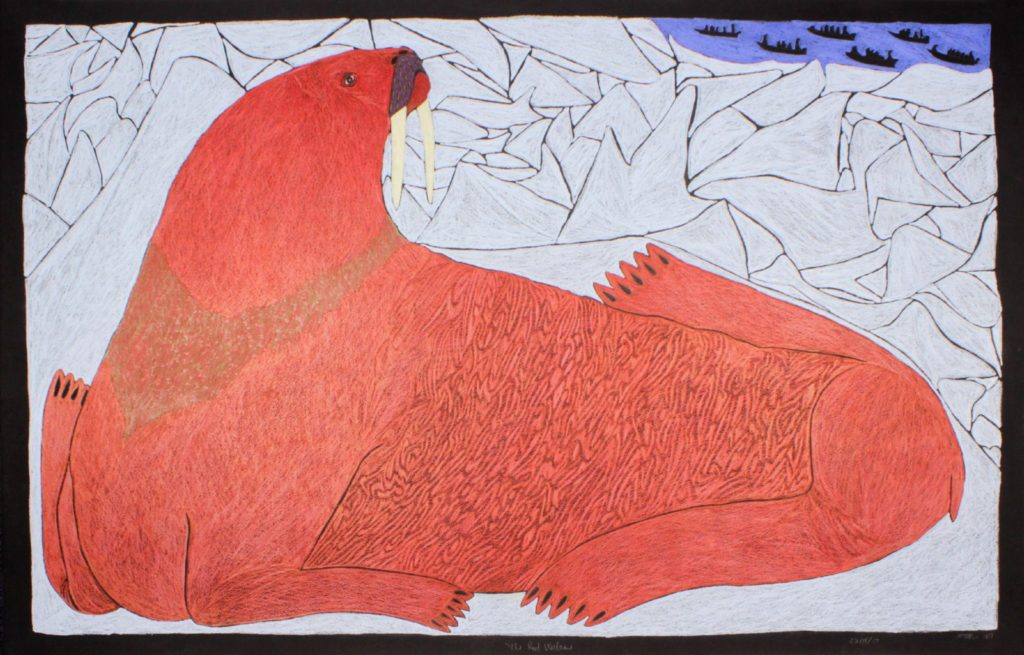

The Red Walrus by Ningiukulu Teevee, Inuit, Cape Dorset, colored pencil, 30” x 44” (2017). Photo courtesy of Feheley Fine Arts and Dorset Fine Arts.

The Red Walrus is a curious work for a number of reasons. First, the viewer is left to wonder why the artist created a walrus that is red. Perhaps it was just for humorous effect or it it may suggest that the setting sun has cast a crimson hue on the huge creature, which dominates the page because of its color and size. Behind it the jagged imagery suggests that the animal is resting on an ice floe while in the distance kayaks approach bearing hunters. Through the use of red, Ningiukulu has created a visually commanding work.

Red Walrus by Tim Pitsiulak, lithograph , /50, Paper: Arches Cover White; Printer: Niveaksie Quianaqtullaq, #2, 29.5” x 41.75” (2016). Photo courtesy of Arctic Artistry Gallery and Dorset Fine Arts. Collection of E. J. Guarino.

The drawing may also be Ningiukulu Teevee’s homage to fellow Cape Dorset artist Timootee (Tim) Pitsiulak who died on December 23, 2016 of pneumonia. He was 49. Tim Pitsiulak was one of the most sought-after and influential contemporary Inuit artists. He is best known for his large colored-pencil drawings of Arctic wildlife and scenery as well as his images of Inuit myths and culture. Pitsiulak bridged the traditional and the contemporary. In 2016, he produced Red Walrus, an unusually large print at twenty-nine and a half inches by forty-one and three quarter inches. Although it is a common Inuit printmaking practice to isolate an iconic image of Arctic wildlife on the page, in Red Walrus the figure of the animal takes up almost the entire sheet, making it visually powerful. The walrus is an important animal in the Arctic and one that is dangerous to hunt. However, Tim Pitsiulak chose to render it in whimsical fashion since the creature seems to be doing the backstroke across the page. As with Ningiukulu’s later drawing, the viewer is left to wonder why the artist created a walrus that is red. For whatever reasons the two artists had for producing a somewhat less than realistic portrait of this animal, they, nonetheless, each created an arresting image.

Ningiukulu Teevee’s drawings and prints are imaginative, frequently whimsical, and often contain sly visual jokes. She is familiar with Inuit oral tradition and characters from these stores, such as Sedna, Raven, Fox, Owl, and Loon, often appear in her work, though usually with a humorous or modern slant. At fifty-five years of age, Ningiukulu has become one of the most respected Cape Dorset artists and is poised to take her place among Canada’s important contemporary artists.