Collector's Corner

LIGHTS! CAMERA! ACTION! Native Americans in the Silent Movie Era

When the public thinks of Hollywood actors and actresses, my guess is that Indigenous Americans don’t readily come to mind. That is unfortunate since Native people have been a part of the movie industry since its earliest days. In the first decades of the 20th century, mainstream American audiences were so fascinated with the West and “wild Indians” that Native Americans were romanticized to the point of being fetishized. Often, Indian characters were attired in costumes that were a hodgepodge of apparel from various Native groups as if such details didn’t matter. Chiefs, no matter what their tribal affiliation, were designated as such by the eagle feather war bonnet worn only by Plains Indian men. Such errors were rampant in the movies. Also, more often than not, Native roles were given to non-Native actors. When Native actors were hired they were sometimes used as technical advisors by directors who were striving for accuracy in their work. In spite of many obstacles, a number of unsung Native American pioneers managed to have careers in the budding film industry. Among them were Lillian St. Cyr, James Young Deer, Mona Darkfeather, Ray Mala, and Will Rogers.

Red Wing (Lillian St. Cyr) (1884 – 1974)

When Lillian St. Cyr entered show business she changed her name to Red Wing and was also billed as Princess Red Wing, a title that was extremely appealing to mainstream audiences of the period. In 1906, she married James Young Deer. Both would go on to become power brokers in the earliest days of the film industry. In 1908, Red Wing garnered a bit par in The White Squaw, which was shot, like many Westerns of the early silent era, in the wilds of Fort Lee, New Jersey. At the time, the movies were very much an East Coast phenomenon. By 1909, Red Wing was hired for a small role as a Native woman in The Mended Lute, a Cecil B. DeMille film in which the villains were white and the Indians were victorious.

When the film industry moved to California, so did Red Wing. In 1914 she became the first Native woman to star in a feature film – The Squaw Man, which was also directed by DeMille. Red Wing, who was Winnebago, played a Ute woman involved in a doomed marriage to an Englishman.

Red Wing’s career was short, lasting approximately fifteen years. During that time she made thirty-five one and two-reel Westerns, often portraying a variety of Native Americans, usually as the romanticized “Indian maiden”. Over time, because she gained weight and grew older, she was no longer considered for the type of roles she once played.

Red Wing and her husband, Jame Young Deer were among the most influential couples in the film industry during the silent era.

James Young Deer/James Young Johnson (1876 – 1946)

Although he was usually identified as Winnebago, like his wife Red Wing, James Young Deer was actually Nanticoke. He became a producer, director, actor, screenwriter, stuntman, and general manager of a studio. Although at one point he became embroiled in a scandal and fled to England, Young Deer is unique in the annals of film history. In his movies, it is not the Indians who are the villains. If an Indian killed a white person they had a good reason for doing so and, it is said, audiences cheered. In his films, Native American characters were three-dimensional rather than stereotypes.

During the course of his career, James Young Deer acted in, wrote, or directed over 150 films. Sadly, much of his early work has been lost. Although today he and his work are all but forgotten, James Young Deer was one of the most successful filmmakers of the silent era. He was the first Native American movie director and it was many years before there was another. He directed such films as Red Wing’s Gratitude (1909), White Fawn’s Devotion: A Play Acted by a Tribe of Red Indians in America (1910), The Red Girl and the Child (1910), A Cheyenne Brave (1910), An Indian’s Gratitude (1910), Cowboy Justice (1910), The Yaqui Girl (1910), Red Deer’s Devotion (1911), The Unwilling Bride (1912), The Squaw Man’s Sweetheart (1912), The Savage (1913), Who Laughs Last (1920), and Lieutenant Daring RN and the Water Rats (1924).

Mona Darkfeather/Josephine M. Workman (1883-1977)

Known as Mona Darkfeather as well as Princess Mona Darkfeather, Josephine M. Workman starred in 102 films during her career, which lasted from 1910 to 1917. Darkfeather played Native American roles in Indian and Western one-reelers and full-length films, but is best remembered for her role as Prairie Flower in The Vanishing Tribe, a 1914 film based on a Native American legend. Darkfeather also frequently played Spanish women, but became most famous for her ability to perform stunts while riding a horse bareback.

Although her paternal grandmother was from Taos Pueblo, Darkfeather was predominantly of European and Chilean heritage. However, she was promoted to audiences as being full-blooded Blackfeet. She claimed that she had been made a blood member of the Blackfeet Nation and had been given the title of princess by a Blackfeet chieftain.

Cecil B. DeMille wanted Mona Darkfeather for the role of Nat-u-ritch in his 1914 Western The Squaw Man. However, because of her popularity, her schedule was full and she was unable to accept the role. Instead, it went to Red Wing (Lillian St. Cyr).

Ray Mala/Ray Agnaqsiaq Wise (1906 – 1952)

The son of a Russian Jewish immigrant father and an Inupiaq mother, Ray Mala’s movie career bridged the silent and sound eras. Considered by many to be the first Native movie star, he has been called the “Eskimo Clark Gable”.

Mala arrived in Hollywood in 1925, a few short years before the dawn of the sound era, and secured a job as a cameraman. Perhaps because of his good looks, he soon landed a lead role in Igloo, a “staged documentary” of the early sound era that was filmed in Barrow, Alaska. The film was a hit. At this time, mainstream America was obsessed with all things Native, which they perceived as mysterious, exotic, and primitive. Alaska was particularly fascinating. It was not yet a state and most Americans knew very little about it.

Based on Igloo’s success, in 1933 Mala was cast in Eskimo/Mala the Magnificent in which his first wife was played by a Chinese-American actress, and his second wife was played by a Japanese-American actress. The film was the first to be shot in a Native American language – Inupiat. Because of poor box-office, the title was changed to Eskimo Wife-Traders, which would be titillating to mainstream audiences.

Ray Mala went on to play many types of Native people, particularly Polynesians. He was cast as the lead in Last of the Pagans (1935), which was filmed on location in Tahiti, and also appeared in The Jungle Princess (1936) with Dorothy Lamour, His other noteworthy films include Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940); Union Pacific (1939), a Cecil B. DeMille film; Son of Fury (1942), which starred Tyrone Power; and The Tuttles of Tahiti, which starred Charles Laughton, with Mala once again cast as a Polynesian. However, Mala is probably best known for Robinson Crusoe of Clipper Island, a fourteen-part serial that was one of the first to be made by Republic Pictures.

During his career, Ray Mala appeared in more than twenty-five films, but he also spent time behind the camera. He worked as a cameraman on Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) as well as on Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944).

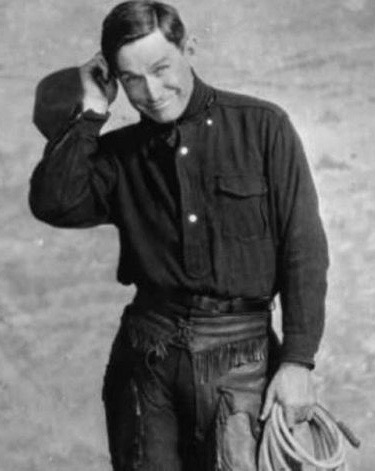

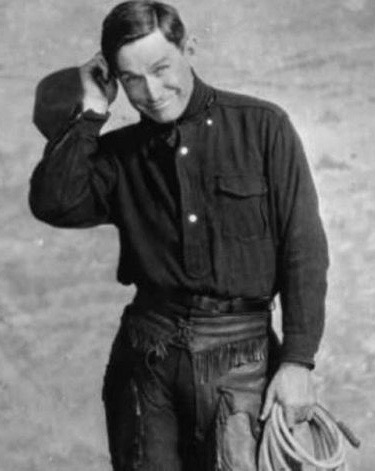

Will Rogers/William Penn Adair Rogers (1879 – 1935)

Like Ray Mala, the career of Will Rogers spanned the silent and sound eras of motion pictures. Rodgers was one of the most famous and most beloved Americans of the early 20th century. Born in Oologah, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), he was a cowboy, vaudeville performer, stage and film actor, radio personality, newspaper columnist, humorist, and social commentator. Will Rogers performed in Wild West shows Vaudeville, on Broadway, in the Ziegfeld Follies, on radio, and in silent and sound films. Between 1918 and 1928 he appeared in forty-eight silent films and between 1929 and 1935 in twenty-one sound films. Unlike other Native American actors of the period, Rodgers was never typecast as an Indian. He played a variety of roles but mostly played himself since the public came to love the persona of the honest, plain-talking, homespun, down-to-earth guy he created.

Will Rogers died on August 15, 1935, in a plane crash in Point Barrow, Alaska. He was mourned by millions. In 1948, the U.S Postal Service issued a stamp honoring him.

Some of Will Rogers’ most famous quotes:

America is a land of opportunity and don’t ever forget it.

We will never have true civilization until we have learned

to recognize the rights of others.

Mothers are the only race of people that speak the same

tongue. A mother in Manchuria could converse with a

mother in Nebraska and never miss a word.

My ancestors didn’t come over on the Mayflower, but they

met the boat.

I never met a man I didn’t like.

America can carry herself and get along in pretty fair shape,

but when she stops and picks up the whole world and puts it

on her shoulders she just can’t “get it done.”

There were other Native Americans who worked in the film industry during the silent era including Dark Cloud/William Eagle Shirt (Lakota), Elijah Tahamont (Abenaki), Jessie Cornplanter (Seneca), and Chauncey Yellow Robe (Lakota), though they did not achieve the fame of Lillian St. Cyr, James Young Deer, Mona Darkfeather, Ray Mala, or Will Rogers. These artists acted in movies at a time when the Hollywood studio system did not yet exist nor was under the control of businessmen. Nonetheless, they faced most of the same problems contemporary Native actors and actresses still encounter. In a speech he gave in 1913, Chauncey Yellow Robe made it abundantly clear that Native actors and actresses were well aware of the obstacles before them. “He [the Indian] is exhibited as a savage in every motion picture theater in the country,” he said. Although these Native men and women knew that movies distorted and stereotyped Native Americans and their cultures, what they could do about it was very limited.

Like everyone else, Native Americans go to and are influenced by the movies. However, even today they rarely see their lives, history or culture accurately portrayed. Native actors are still rarely cast in any parts and films about Native Americans are few and far between. For far too long, audiences have been seeing Native life through non-Native eyes. Contemporary Native Americans want to tell their own stories from their own unique perspective. As more Native people find employment in the film industry, they will have more chances to portray their varied cultures in positive and truthful ways.