Collector's Corner

RICK BARTOW: REMEMBERING AN AMERICAN MASTER

As a collector, one of my very few regrets is never having met Rick Bartow. I have been an admirer of his work since 2003 when I saw Continuum: 12 Artists at the National Museum of the American Indian in Manhattan. I had never seen anything like Bartow’s pieces before and determined to know more about the artist and his work. Fortunately, the wall texts indicated that many of the works on view were on loan from the Froelick Gallery in Portland, Oregon, a city I was scheduled to visit in a few weeks. On that trip I acquired three works on paper by the artist and, over the years, I have managed to add prints, sculptures, and even a small painting by Mr. Bartow to my collection whenever I could.

I had hoped to meet the artist, at last, when Rick Bartow: Things You Know But Cannot Explain, a touring retrospective exhibition of the artist’s work, opened at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe in August 2016. Sadly that was not to be. Rick Bartow died on April 2 of that year. His passing is a great loss. He was one of our country’s greatest contemporary artists. More than ever, I feel that this artist’s work is among the most important in my collection and I resolved to add new pieces to my collection as soon as possible. Doing so is the best way to keep his legacy alive. Since I was again traveling to Portland in August 2016 I made sure to arrange a visit at the Froelick Gallery. Charles Froelick graciously brought out scores of prints and other works on paper by Rick Bartow for me to consider, patiently sharing his vast knowledge about Bartow and his art. After spending almost an entire day in the gallery, I chose five works on paper to add to the collection.

Salmon Boy by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, ed. 4/8, 15″ x 22” image and paper, (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The day I arrived at the Froelick Gallery, the staff was beginning the process of installing Sparrow Song, an exhibit of paintings, sculptures, and prints by Rick Bartow. My attention was immediately caught by Salmon Boy, a print that was framed and lying against a wall, waiting to be hung. As soon as I saw it, I decided that, if I could afford it, I would definitely add it to my collection. Charles Froelick explained that in 2015 the artist “scratched/drew . . . three drypoint images with skeletal images inside . . . .” but they were not editioned until winter 2016. He also added that, at that point, Bartow was barely speaking.

Salmon Boy is quintessential Rick Bartow. It is both surreal and deeply symbolic. It is clear that when the artist produced this work he was keenly aware of his own mortality and that time was growing short. The print contains images of severed fish heads and a boy, perhaps a corpse, superimposed over a somewhat skeletal salmon. One side of the boy’s chest appears to be scratched out and he holds a circle. In this way, the artist associates the transience of human life with that of the salmon, which hatches, travels to the vast oceans where it spends a good part of its life, then, against great odds, travels upstream to its place of origin to spawn and finally die as the cycle begins again. In the salmon’s tail is an eye. It is a symbol that the artist has used in many works. Although it may suggest the All-Seeing Divine, it could just as easily represent the ability of artists to perceive aspects of existence that are closed to the rest of humanity.

Cernunnus by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, ed. 13/16, 8.5” x 7.5” (2003). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The second print I selected is equally mysterious and reflects the artist’s ever inquisitive mind. Cernunnus is dark and troubling. It is Bartow’s interpretation of the Celtic deity Cernunnus (more commonly spelled Cernunnos) who is usually portrayed with antlers or horns and is connected with fertility, life, animals, wealth, and the underworld. Associated with the regenerative power of the forest, the being’s horns symbolize power, sexuality, and fecundity. Among scholars of Celtic lore, Cernunnos is often referred to as “Lord of the Animals” or “Lord of Wild Things.” Rick Bartow was clearly fascinated with this mythic creature and on April 5, 2013 wrote, “The cernunus or elk man came after I met the Irish ambassador down in San Fran in the 80s. We discussed salmon cycles and the rest just followed.”

Ahab by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, ed. 1/6, image: 4.5” x 3.5”; paper: 9.5” x 7” paper (2003). Collection of E. J. Guarino

I was attracted to Ahab because of its allusion to Moby Dick, one of my favorite books and also because Rick Bartow visually captured the torment of Melville’s main character. According to Charles Froelick, The Old Man and the Sea and Moby Dick were the artist’s two favorite books – “the ones he’d want if stranded on an island. Growing up in Newport, Oregon, on the Yaquina Bay, he knew many who spent their lives fishing the Pacific Ocean. He knew the tragedies and the wonder of the open sea. He named many works after characters in Moby Dick.” Looking at Bartow’s Ahab elicits a visceral reaction. One can feel the anguish, hatred, and fanaticism of Melville’s character. It is a powerful creation.

For W. J. by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, drypoint etching, ed. 8/12, image: 4” x 4”; paper: 14” x 10” (1998).Collection of E. J. Guarino

Like Salmon Boy and, to some degree, Cernunnus and Ahab, For W. J. is a contemplation on mortality. The initials W. J. stand for William Jamison. In an Email correspondence Charles Froelick explained: “William Jamison opened his gallery in Portland in 1980. He and Rick were introduced by a mutual friend in 1985 and they began working together. Rick had been showing at community spaces on the Oregon Coast and Willamette Valley and had been included in some very important early ’80’s shows in San Francisco at the American Indian Community House (AICA ) but the relationship with William really boosted Rick’s abilities to focus on just making art. William took Rick’s work to art fairs in Chicago, LA, and NY. Rick and William really hit it off and had a great time working together. Rick’s work began to sell regularly. William promoted him seriously and Rick was able to quit his job to just devote himself to making art. It was the 1980s. William had HIV and he had fluctuations in health. I moved to Portland in ’91 and was hired in early ’92 to help at the gallery while William’s health was not stable. William passed away in 1995. His death was a huge loss for the Portland community. He was so loved. William had encouraged me to open my own gallery, and encouraged Rick and me to work together, so I too owe William a great deal of appreciation. He was a fabulous mentor . . . .”

|

|

Goro Kakei by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, multimedia on paper, image: 14”x 8”; paper: 14” x 8” (1998). Collection of E.J. Guarino

Goro Kakei turned out to be a bit of a revelation, including for the staff at the Froelick Gallery. After I had chosen the piece, I just happened to turn it over and, to the surprise of everyone present, on the reverse side is a self-portrait of the artist, plus an unsigned handwritten note to him. The piece instantly became an artistic mystery, which Charles Froelick and I were determined to solve.

When I saw this particular work I was attracted by the visual strength of the portrait although I had no idea who Goro Kakei might be. When I returned home, however, I queried Charles Froelick about this. “Goro Kakei is a terrific artist, born 1930 in Shizuoka, Japan” he wrote. “He made many prints, sculptures, drawings. Bartow was able to meet him on one of his visits to Japan to see Naoaki Sakamoto, Seii Hiroshima, and Toshiaki Yanagisawa.”

I also posted images of the work on Facebook, which Mr. Froelick reposted. Much to my surprise, it elicited the following response from Seii Hiroshima: “What a surprise, Charles Froelick! I didn’t know Rick had drawn Goro’s portrait. I remember Rick was very much impressed by Goro’s works when I showed him them at my gallery in 1997. The letter behind Rick’s self-portrait must be from KIMURA-San from OGUNI town office.”

The mystery of who wrote the note on the reverse of Goro Kakei was now solved – sort of. If someone called Kimura-san was, in fact, the author of what is written on the back of the work, who was he? I once again contacted Charles Froelick. “Oguni town is the small village where Naoaki Sakamoto has/had a paper making museum and his country house,” Froelick wrote back. “It’s in Niigata prefecture on the northern main island, near the Sea of Japan, mountainous – beautiful! I think Kimura-san was someone who worked for the regional government who helped fund the Oguni community exhibit and meeting house that hosted Rick’s shows. I traveled there in 1997 with Rick, his wife Julie (who died in ’99 from breast cancer), and their son Booker. We visited many locals’ homes for meals and tea”

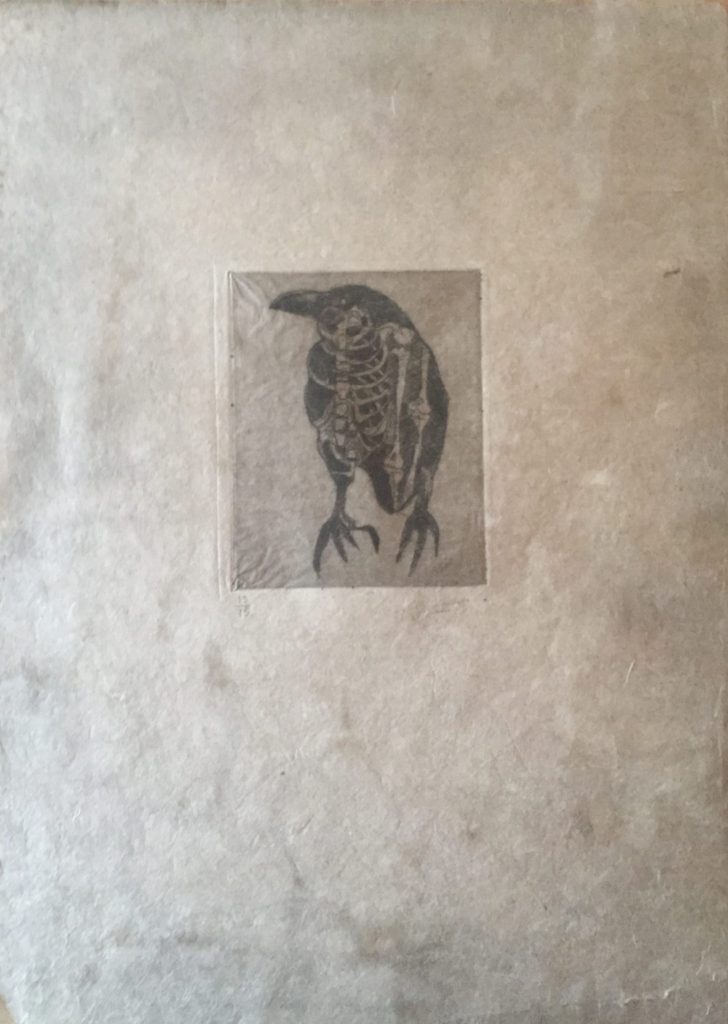

Old Raven by Rick Wiyot, drypoint on handmade Mitsumata paper, ed. /15; Image size: 5” x 4”; Paper size: 16” x 12” (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino

After looking at scores of prints and other works on paper by Rick Bartow at the Froelick Gallery, I could not get many of the images out of my head. Although I returned home having acquired five works, I was determined to add more to the collection. A few months later, I contacted the gallery and purchased Old Raven. This print particularly intrigued me. Created during the artist’s last year of life, it seems to be the essence of what Bartow was trying to express in much of his work. Old Raven is, at once, dark, mysterious, and a bit whimsical. The raven was often one of the artist’s stand ins. It is a bird that is highly intelligent, inscrutable, and a prankster. As presented in the print, the raven assumes other qualities as well. Bartow gives us what resembles an X-ray view of the creature, suggesting we are seeing its inner self. However, the bird’s skeleton appears to be not too dissimilar to that of a human. The print clearly reflects the artist’s coming to grips with his failing health and mortality.

I have been an admirer of Rick Bartow’s work since 2003. From the first time I saw it as part of Continuum: 12 Artists at the NMAI, I felt that I was experiencing a unique voice. Bartow’s art is visually powerful, much of it dark and angst filled but that is not the whole story. Over the years the artist had to deal with his Viet Nam War experiences, alcohol abuse, and the loss of his wife. These struggles inform his art. However, many of his pieces are about hope, strength, and survival in the face of adversity. A number of works also contain Bartow’s sly brand of humor. As an artist, Rick Bartow had many influences that informed his art: his Wiyot heritage, Vermeer, Klimt, Chagall, Max Beckmann, Francis Bacon, and Hieronymus Bosch as well as Expressionism, Surrealism, Japanese prints and more than a few pieces contain literary or musical allusions.

Rick Bartow is one of our most important contemporary artists. He produced work that is both intense and visceral. Whether it is the surreal and expressionistic power of his paintings and prints or the raw elemental quality of his sculptures, Bartow’s work is always moving and visually arresting. It reflects the concerns of an artist trying to sort out the complexities and disappointments of life. Often filled with pain, rage and, sometimes, humor, Bartow’s art cannot easily be confined solely to culturally based interpretations. It is mysterious, complex, and defies categorization. In addition to advocating for its exhibition, over the years I have tried to collect as much of the artist’s work as possible and will continue to due so. It is the best way to keep Rick Bartow’s rich legacy alive.

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Charles Froelick, owner of the Froelick Gallery, for his invaluable help with this article.