Collector's Corner

SMOKE SCREENS: The Uneasy Relationship Between Native Americans and the Movies

For well over a century, images of Native Americans have been flashed across movie screens worldwide. The tales of “wild Indians” and “noble savages” that audiences devoured as emblematic of the American West were illusions on more than one level. For the most part, the stories have been fictitious but, even when based on fact, Native people have been stereotyped and their cultures misrepresented. Another source of tension between Native Americans and the Hollywood film industry is that Native actors are rarely cast in any parts and the few Native roles that have existed have been given to non-Native actors – Jeff Chandler as Cochise in Broken Arrow (1950), Burt Lancaster in Jim Thorpe – All-American (1951), Chuck Connors in Geronimo (1962) and, most recently, Johnny Depp as Tonto in The Lone Ranger (2013) and Benicio del Toro as the title character in Jimmy P. (Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian). Although putting on blackface has long been unacceptable, the same does not seem to hold true for “redface.”

Red Raven, Red Raven by Thomas Greyeyes, screenprint, /25, Dine, 19” x 15” (2013). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Reactions among Native Americans to Johnny Depp being cast as Tonto were mixed. It ranged from acceptance (Depp is, after all a highly respected actor who was aware of the sensitive issues surrounding the role) to disappointment and anger. Artist Thomas Greyeyes’ response was Red Raven, Red Raven, a screenprint that shows Depp killing the bird that Tonto wears as a headdress throughout the film. Used for comic and satiric effect in the movie, in Greyeyes‘ work it is employed as political and social commentary on the nature of identity. The print portrays Depp squeezing the blood out of the raven’s mouth as if by coloring his skin red he could turn himself into a Native American. Although the tone of the film is humorous and satiric, with the Lone Ranger repeatedly saved from his foolish escapades by his Indian sidekick, it still manages to distort the original meanings and purposes of many aspects of Native culture, including the iconic raven headdress. In Red Raven, Red Raven, Thomas Greyeyes has created a powerful image, particularly because of his use of red connected with the blackness of the raven and the white paint of Tonto’s face. The work’s title may also be a sly reference to the children’s schoolyard game of Red Rover, Red Rover, suggesting Hollywood’s immature and misinformed ideas about Native Americans.

Lone Ranger Love by Susan Folwell, Santa Clara Pueblo,

acrylic paint, native clay, 9”w x 9.75”H (2013).

Susan Folwell takes a decidedly more benign approach to the iconic masked man in Lone Ranger Love. Referencing the Pop Art movement, particularly the work of Roy Lichtenstein, this piece is a clever and subtle commentary on some of the more exotic aspects of eroticism. In addition to the pot’s vaguely phallic shape, Folwell employs the image of a masked male about to kiss a heavily made up and, obviously, willing female – something the Lone Ranger never did in the long running TV series – and may suggest that the two figures are involved in sexual role playing or even bondage. It is also a way of lampooning the chaste hero who never “got the girl.” He was only interested in righting wrongs and then riding away, his true identity unknown. The jar’s cylindrical shape and the use of panels to contain the images are suggestive of movie and TV screens; the intentionally limited color palette – white, black and grey – of the figures alludes to the black-and-white Westerns that were once so popular.

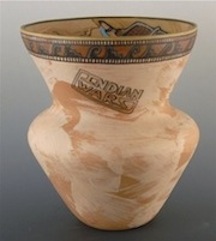

Indian Wars by Susan Folwell, Native clay, Native slips, Santa Clara Pueblo, 8”w x 8.75”h (2013). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Folwell once again appropriates popular culture, giving it a “Native twist” in Indian Wars, a work that references Star Wars and a famous photograph by Edward S. Curtis. The artist employed a white clay slip over the brown clay, giving the outside of the piece a sandy, textural quality reminiscent of Southwestern landscapes and that of the fictional planet Tatooine. Around the jar’s neck the words Indian Wars appear in several locations. The reference to film as a medium is reinforced by a band of cloud and lightening designs with rain patterns that, when viewed from a few feet away, appear to be strips of film. Folwell uses the jar’s unusual shape to artistic advantage by painting within the neck rather than on the outside as would be expected. This forces the viewer to look deep within the piece.

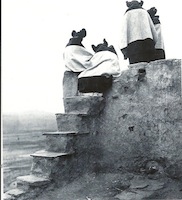

Hopi Women, 1906 photo by Edward S. Curtis.

The interior imagery of Indian Wars shows Hopi maidens grouped as they are in Hopi Women, the historic photo by Edward S. Curtis. The landscape they look out upon could be the Hopi Mesas, Monument Valley or Tatooine. In the distance is a Pueblo village and in the sky a TIE fighter from the Star Wars films. Opposite the women is a Land Speeder driven by a young girl with braids who could be Princess Leia or she could be Hopi. On the craft’s back corner is a hand print, a reference to those put on their horses by Native American warriors. The coloration inside the piece gets darker as it moves away from the rim, creating the illusion that the viewer is looking into deep space.

Folwell often uses her art to critique and comment on society, politics and history. In Indian Wars, she symbolically suggests a connection between the fight waged by American Indians against the U.S. Government and that of Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia and the Rebel Alliance against the Galactic Empire. This conceit is not far-fetched: At the time of its release, a number of critics referred to Star Wars as a “Space Western.”

According to the artist, Indian Wars is the maquette for Star Wars, a much larger piece (See below). The artist’s inspiration for the jar came about in an unusual way: “George Lucas worked with people from the Navajo Nation to produce the first Star Wars film dubbed into Navajo. . . . Can you imagine!” Folwell said. “In Navajo? I knew it was coming soon and was compelled. Although the ‘scenery’ is from the Aniken Skywalker movie, it lent itself well for imagery I was looking for”

Star Wars by Susan Folwell, Native clay, Native clay slips acrylic paint, Santa Clara Pueblo, 14” w x 9.25″h (2013). Photo courtesy of King Galleries of Scottsdale.

Star Wars (base)

Star Wars (base) Star Wars (inner lip)

Star Wars (inner lip)

_____________________________________

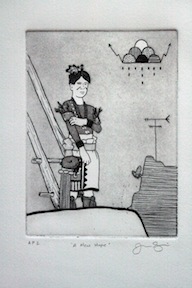

A New Hope by Jason Garcia, Santa Clara Pueblo, etching and aquatint, 1/5; Paper size: 11”w x 14”h; Plate size: 6”w x 8”h (2013). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Like Susan Folwell’s references to Star Wars, Jason Garcia’s allusions to the movie in his print A New Hope are textural and visual. When it was originally released in 1977, the film was simply Star Wars. However, for its 1981 re-release the title became Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. Jason Garcia explained in an Email, “My work . . . appropriates different aspects of popular culture. The title A New Hope refers to Star Wars and also reflects the scene of Luke Skywalker watching the sunset on Tatooine.”

The central image of Garcia’s print is a male dressed for the corn dance at Santa Clara, which takes place on August 12th. The ceremony celebrates Saint Clair of Assisi, for whom the pueblo is named. Ironically, Saint Clair is also the patron saint of television as well as of the blind. Beyond the figure one can plainly see an antenna and a satellite dish. The artist went on to say, “ . . . I use . . . antennas and satellite dishes (along with cell phones) as a symbol of technology and also as a symbol to tie the work back to Santa Clara.” Hovering above is an abstract design representing a rain cloud, symbolic of fertility and of Life. The scene, clearly set in the 21st century, presents the young male corn dancer, and by extension all young people, as the hope of the future.

Apocalypto, 2011 by Diego Romero, Cochiti Pueblo, two color lithograph, XII/XII, 26” x 26” (2011). Collection of E. J. Guarino

The science fiction genre was also referenced by Diego Romero in Apocalypto, 2011. In this work, the artist appropriates the central image from the final, iconic scene of the 1968 film Planet of the Apes but the title of the piece is a subtle allusion to Mel Gibson’s 2006 film Apocalypto, which was controversial for its portrayal of Mayan Indians. The use of the Statue of Liberty in the original Planet of the Apes was shocking because this important national symbol was used to suggest the destruction of the United States and by extension the demise of the human race. What makes the Romero print disturbing is its ambiguity. To the left of the damaged Statue of Liberty is a kneeling Keith Haring-like figure with upraised arms and clenched fists whose hairstyle and wrist and ankle bands suggest that this is a Native American. Done in the style of comic book art, marks around the arms and radiating from the head indicate emotion. However, the viewer is left to wonder if the Indian is anguished or exultant over the destruction of one of America’s most beloved treasures. That fact that Lady Liberty’s Torch of Freedom is still held high and her book with the date July 4, 1776 in Roman numerals remains intact may be a clue.

Gone with Him 6 by Sarah Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, woven photographs with mylar and artist tape,12″ x 36″ (2012). Collection of E. J. Guarino

In her Gone with Him series, Sarah Sense takes on Gone with the Wind, another of Hollywood’s most famous films. Made in 1939 and set in the mid-1800s, the film was, and still is, controversial for its portrayal of African-Americans and slave owners as benevolent. However, the role of Native Americans in the Civil War and the affects it had on various tribes is not even considered. It is as if American Indians just didn’t exist.

By inserting herself in provocative ways into well-known images from Gone with the Wind, Sarah Sense reframes the narrative, putting herself on an equal footing with the film’s stars. By doing so, she forces viewers to reconsider their attitudes with regard to Native sexuality, the treatment of Native Americans throughout U.S. history and Hollywood’s portrayal of Indians. Sense reinforces her control of the discussion from a Native perspective by employing traditional Chitimacha weaving techniques with contemporary materials and images from iconic Hollywood movies.

Remembering Wild Strawberries by Gail Tremblay, Onondaga Iroquois, 16mm film stock, red leader and metallic yarn and braid, 7 ½” x 5” in diameter (2004). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Traditional basket weaving techniques are also an important aspect of Gail Tremblay’s Remembering Wild Strawberries, a thoroughly modern work fashioned from decidedly non-traditional materials. Constructed of 16mm film stock, red leader and metallic yarn and braid, the work references the classic Iroquois strawberry basket form. However, as the title suggests, the artist is not simply interested in producing an unconventional version of an historic basketry type. Remembering Wild Strawberries not only pays homage to the importance of the berry in the Iroquois afterlife, it is also an allusion to a masterpiece by Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. In Iroquois spiritual belief, strawberries nourish the souls of the departed on their journey to the Great Spirit. In the Bergman film, in which an elderly man remembers his life and loves, the strawberry becomes a symbol of youth, remembrance, and lost love. In her unique take on a well-known basketry form, Gail Tremblay challenges the viewer’s notions about what is traditional. By making the basket out of footage from an educational film she also references her role as an educator who is teaching us to see in new ways. In connecting her work to a classic Swedish film Tremblay asks us to consider our ideas about contemporary Native Americans. One can only wonder how many people would be surprised that an American Indian is familiar with the work of a Swedish director.

Wish Jar with Flute Player and Plants by Al Qöyawayma, Hopi, 5” w x 6.75”h (2014). Photo courtesy of King Galleries of Scottsdale.

Sometimes, allusions to films by Native artists in their work are subtle and oblique. While visiting King Galleries during Heard Indian Market week, Al Qöyawayma saw me admiring his Wish Jar with Flute Player and Plants and said, almost conspiratorially, “That piece contains a reference to Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” Seeing the puzzled look on my face, Mr. Qöyawayma explained that there were five notes on the jar, each a different color, which represented the notes in the film that the humans employed to communicate with the extraterrestrials. Then, he demonstrated, “Da, da, da, da, DA.”

Since the inception of motion pictures, Native Americans have been stereotyped by the medium. Often Indians belonging to one tribe were incorrectly attired in costumes that were a hodgepodge of apparel from various Native groups as if such details didn’t matter. Chiefs, no matter what their tribal affiliation, were designated as such by the eagle feather war bonnet worn only by Plains Indian men. Such errors are rampant in Hollywood films. Compounding the problem is the fact that historically, more often than not, Native roles were given to non-Native actors.

Like everyone else, Native Americans go to and are influenced by the movies. However, rarely do they see their lives, history or culture accurately portrayed. For far too long, audiences have been seeing Native life through a series of smoke screens. As a response, many contemporary Native artists appropriate aspects of film for their own artistic purposes. Contemporary Native Americans want to participate in telling their own stories from their unique perspective.