Collector's Corner

THE IMPROBABLE COLLECTOR

Collecting is a strange endeavor. It means different things to different people. Each person has an individual path that brought him or her to this pursuit. In many cases, if not most, an individual becomes a collector long before realizing it. That was certainly the case with me. I began by buying pieces I thought were interesting or beautiful to decorate my apartment. It was only after I had acquired a considerable amount of objects that I realized that I was, in fact, a collector and decided I should become organized and approach what I was doing in a serious manner.

|

|

Mold-made black-on-white pot by Josephine Garcia-Oak (unsigned), Acoma, 4½”h x 5”w (circa early 1980s). Collection of E. J. Guarino

About fifteen years into collecting the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College produced Forms of Exchange, the first exhibit from my collection. In preparation, one of the experts who came to my home to select works was Bruce Bernstein (currently Director of Innovation and Chief Curator at the Coe Foundation for the Arts). As he looked at the pottery, he pointed out a mold-made piece. Horrified, all I could do was mumble something about the piece being among the first that I had ever collected; that I hadn’t known what I was doing; and I vowed to throw it out. Always gracious, Bruce said that it would make a great teaching tool and I have used it as such to great effect ever since. To make matters worse, in all the years the piece had been in my collection I had never realized that it was mold-made until that fact was pointed out to me. I had acquired it at a pow wow in Upstate New York in the first flush of collecting excitement at a time when I was buying indiscriminately. To this day, I have never revealed to Bruce that at that very same pow wow I purchased a “Native American basket” that turned out to be African. The word dummkopf comes to mind. Over the years, when I referred to myself as the “oddball collector” it was Bruce who said that I should more properly be called the “improbable collector.”

Guernica, open bowl by Diego Romero, Cochiti Pueblo, 13.5” diameter x 6” deep, gold leaf painting on the inside rim (2007). Signed: Chongo made and painted me “Guernica” Collection of E. J. Guarino

When I was first becoming known as a collector, a gallerist told me, “You have become a sophisticated and astute collector. There’s no need to mention your working-class background.” I thought that over for about a nanosecond and decided that my personal history was very much a part of who I was as a collector. Often, when I spoke to groups about collecting the theme was “If I can become a collector, so can you.” People responded. They wanted to hear about the Italian-American kid who was raised in the poorest section of his hometown, who became a high school teacher and somehow managed to put together a large collection of Native American and Inuit art. Growing up, there were many things my parents told me that I could not do because “it’s not in our category.” That was code for “We can’t afford for you to do it.” However, no one ever told me I could not become a collector because there was no one in my family or milieu who could have ever imagined such a possibility. To those around me, the idea of my becoming a collector would have been as farfetched as my suddenly sprouting wings and flying. Nonetheless, here I am.

Artifice multi-hole Breach Series vessel by Courtney M. Leonard, Shinnecock Nation, mica clay, handmade glazes with blue slip-on interior, 9.25”w x 12.5”h (2016). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Over the course of almost thirty years, the collection had come to encompass pottery, baskets, beadwork, textiles, masks, headdresses, katsinas, jewelry, sculpture, paintings, and works on paper. During this time I lost interest in some collecting areas and new ones arose. When I was no longer actively collecting in a particular vein I would donate what I had acquired to a museum – the Brooklyn Museum, the Coe Foundation for the Arts, and the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College. I deaccessioned all of the historic and contemporary Iroquois beadwork, the historic Micmac beadwork, all of the Mata Ortiz pottery, and much of the basketry. As works were leaving the collection new ones were entering it.

Animals Out Of Darkness, signed Kenojuak Ashevak, but known to be the work of her husband Johnniebo Ashevak (1923-1972), Cape Dorset, stone-cut on paper, 5/50, 19½” x 21¾” (1961). Ex-collection of Honorable Mark M. de Weerdt, Chief Justice, Northwest Territories, Canada. Collection of E. J. Guarino.

In 1995, while traveling in Canada, I saw my first pieces of Inuit art. I had no idea what I was looking at since I had never seen anything like it before, but I was fascinated. I collected a number of sculptures, but it was the works on paper – first drawings, then prints – that intrigued me and still do. Twenty-five years later, Inuit art remains a major part of my collection.

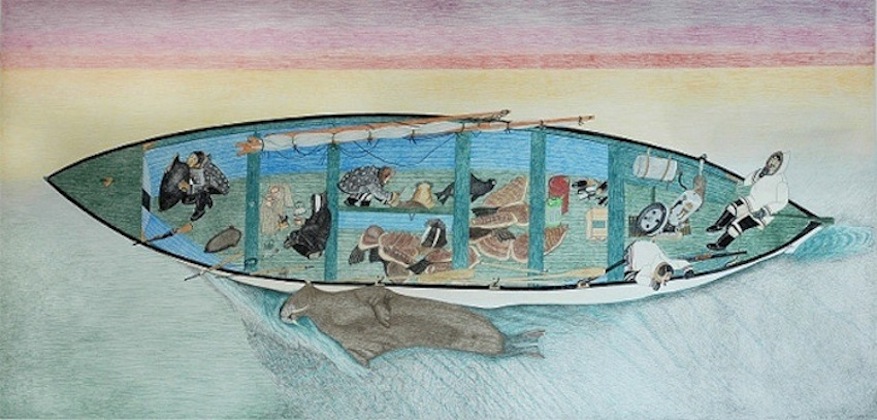

Untitled drawing by Kananginak Pootoogook, colored pencil & ink, Inuit, Cape Dorset, 48” x 96” (2009). Artist’s inscription: “Successful walrus hunt.” Collection of E. J. Guarino.

One of the joys of collecting is how it can enrich your life and can take you in directions you never dreamed possible. In 2013/14, Composition (Successful Walrus Hunt), a mural-sized drawing by Inuit artist Kananginak Pootoogook was exhibited as part of Decolonizing the Exhibition: Contemporary Prints and Drawings from the Edward J. Guarino Collection, which was presented by the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College. While on view, the work was seen by Nancy Rosoff, Andrew W. Mellon Curator and Chair of the Arts of the Americas, Brooklyn Museum, and Associate Curator Susan Kennedy Zeller (now retired) who asked if the work could next be borrowed by the Brooklyn Museum. During the six months it was on display at the Brooklyn Museum, the drawing was noticed by Christine Macel, the curator of Viva Arte Viva, the 57th International Venice Biennale, who chose it as one of the works to be included in the Biennale that was held in 2017. I traveled to Venice and had the thrill of a lifetime seeing work from my collection in this prestigious venue.

Color of Conflicting Values by Shan Goshorn, Eastern Band Cherokee, Arches watercolor paper printed with archival inks, acrylic paint, gold foil, app. 14” x 14” x 13” (2013). Collection of E. J. Guarino. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

About twelve years ago, I became interested in works on paper created by Pueblo ceramic artists whose work was in my collection. However, Andrea Hanley, currently Chief Curator at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, encouraged me to broaden my collecting in this new area to encompass works on paper, not just by Pueblo artists, but by artists from a wide range of Native backgrounds as well. Thus began a new and exciting quest.

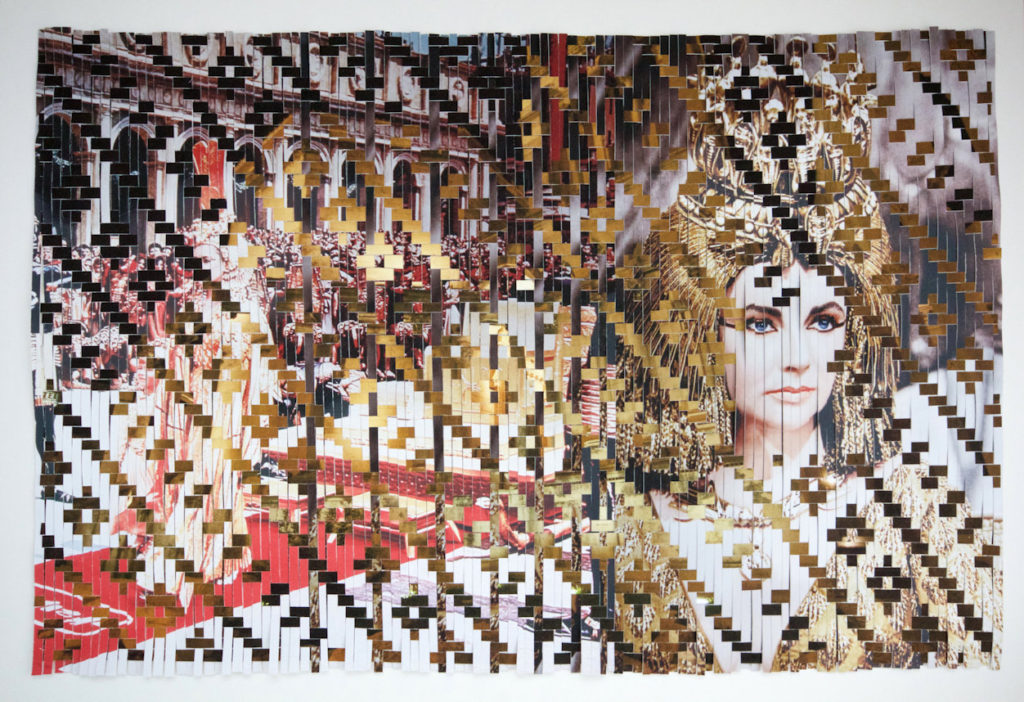

Elizabeth as Cleopatra by Sara Sense, Chitimacha/Choctaw, archival inkjet prints, tape, 18” x 27” (2015). Collection of E. J. Guarino.

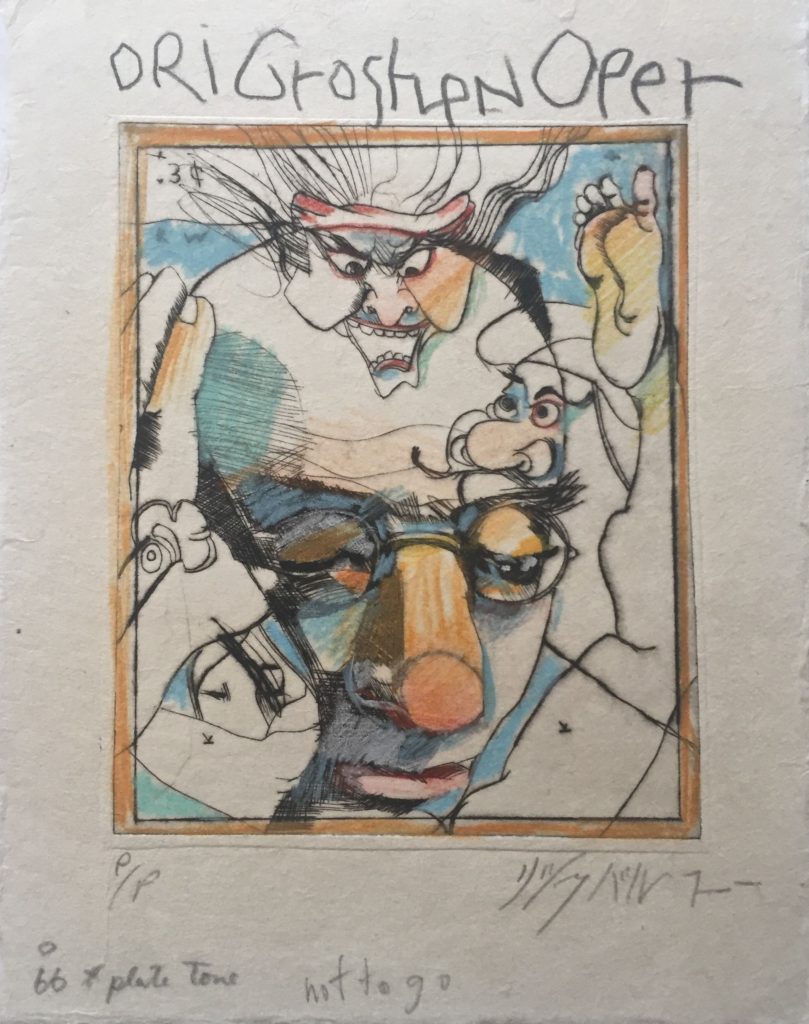

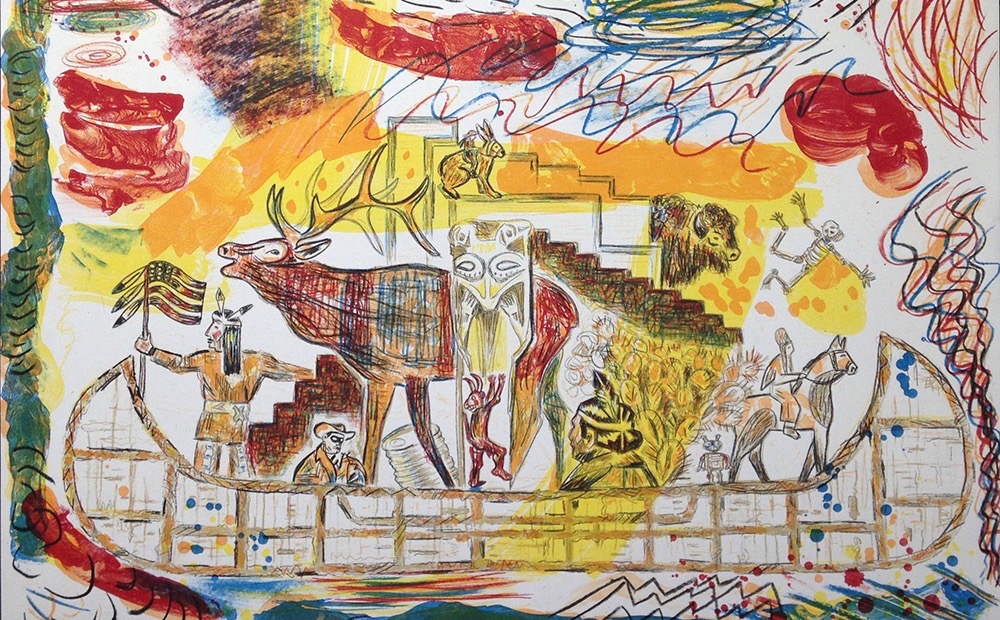

The Native American works on paper portion of the collection are one I find particularly stimulating because it is so diverse. Among hundreds of works, there are four modernist paper baskets by Shan Goshorn; twenty-nine woven pieces, which incorporate photographs, by Sara Sense; thirty-two works by Eliza Naranjo Morse, including a “paper painting”; thirty-seven prints by Rick Bartow; three of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s Trade Canoe prints; and, most recently, photographs by Cara Romero. A wide range of artists – beginning, emerging, established, and superstars – are represented as are a wide range of themes.

Feather by Eliza Naranjo Morse, Santa Clara Pueblo, “paper painting” made of paper, glue, sharpie, wood, thread, 18.5“ x 20.25“ (2011). Collection of E. J. Guarino

From the beginning I have always gone my own way. Having almost no contact with other collectors has given me a unique perspective. When I see other collectors at places such as the Santa Fe Indian Market or in galleries, I enjoy listening and observing. Over the years, doing so has allowed me to see the various ways in which people collect and their reasons for doing so. Although each collector has similar interests to mine his or her collecting style differs greatly from my own. There is no one way to collect. Some collectors will only buy works that have won awards; others will only buy from galleries, never directly from an artist; and there are those who will only acquire the work of artists whose work has received the imprimatur of celebrity. Of course, there are collectors who acquire art simply for financial reasons. That is their prerogative. However, I would never encourage anyone to collect for this reason which, in my opinion, simply becomes a process of amassing “things.”

One collector I met only acquired Zuni fetishes and miniature pottery. When he did add larger ceramic pieces to his collection they had to be “perfect” according to his very exacting standards. Rather than buying intuitively after developing an “eye,” he learned as much as he could about all the technical aspects involved in creating a ceramic work and developed specific criteria for acquiring a piece of pottery.

Bertolt Brecht/3 Penny Opera/Dri Groshen Oper by Rick Bartow, Wiyot, hand-colored drypoint etching, ed. PP/, 7” x 5.5” (1999). Collection of E. J. Guarino

Another collector, who contacted me a few years ago, only collects original abstract works on paper by American artists. Her concern was that no Native artists were represented in her collection and she wanted to remedy that situation. However, she was facing a few obstacles since only drawings or monoprints would fit the collecting parameters she had set up for herself. Complicating matters was the fact that she only collected abstract works. There are Native American artists who produce abstract works on paper, but it has been my experience that the overwhelming amount of works on paper produced by Native artists is representational. I suggested some artists and the collector diligently spent over two years doing her research and, in that time, has added the work of Andrea Carlson, Athena La Tocha, and George Morrison to her collection and is continuing her pursuit in this collecting area.

Trade Canoe: A Western Fantasy by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Salish, Confederated Salish, and Kootenai Nation, MT, lithograph, 18/40; printed by Landfall Press, Santa Fe, NM; published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in conjunction with the exhibition The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, 21” x 30” (2015.).

Many of the artists whose work is in my collection have become dear friends who have told me about their artistic process in private conversations, which they have generously allowed me to use in articles about their work. One of the great pleasures of collecting the work of living artists is getting to know the person who created the piece you have acquired. Whenever I look at a work in my collection I appreciate it for its artistic excellence, but if I know the artist who created it the experience takes on an added richness.

Kaa by Cara Romero, Chemehuevi, archival pigment photograph, 49 5/8” x 43 1/4” x 11 1/2” (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist. Collection of E. J. Guarino.

Like other collectors, I have a collecting philosophy: Everyone should have access to art. Although I am passionate about the art I collect, I don’t believe in hoarding it. For that reason, I am always happy to loan works from my collection to museums. I see doing so simply as an extension of my teaching career. As a collector of Native American and Inuit art, I feel it is particularly important to support living artists, advocate for their art, and make it accessible to as wide an audience as possible. Even an improbable collector can achieve these goals and I am constantly working to do so.